GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, June 28, 2000

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] "Taming of the Shrew"

[03] "Hamlet"

[04] "Henry V"

[05] Goethe's & Dietz's "Force of Nature"

[06] Williams' "Night of the Iguana"

[07] Kaufman & Hart's "Man Who Came To Dinner"

[08] Margaret Edson's "Wit"

[09] Lynn Nottage's "Crumbs from the Table of Joy"

[10] Preview of 2001 Attractions

[11] New Theatre for Ashland Festival

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

LOOK WHERE IT COMES AGAIN!

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival—

Ashland's Annual Arts Event Since 1935

The Bard Outdoors—in the Elizabethan Theatre:

Twelfth Night—

| |

| HUGGING THE BEAR--Cesario/Viola [Vilma Silva] consoles love-sick Orsino [Armando Durán] in Ashland's "Twelfth Night." Photo: ©David Cooper, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

Indeed, it was not all that soothing, nor conducive to amorous fantasies. Perhaps it is time to revive "Your Own Thing," that charming Mod musical version of "Twelfth Night"?

For those who can still remember the Love Generation, Orson was running a disco, and Viola, disguised as a boy, was hired to fill in for one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse combo.

Disease was sick and couldn't play that gig.

Orson was as smitten with Viola/Cesario as she was with him. But in Danny Apolinar's musical, Orson consults a book on homosexuality to untangle his confused emotions.

Was he relieved to discover Viola's true sexual identity and orientation!

So is Duke Orsino in Ashland, though his instinctive attraction for the lovely page Cesario [Vila Silva] was entirely understandable. As either boy or girl, she was outstanding and passionate.

Catherine Lynn Davis, as the deeply mourning Olivia, was quite as attractive and charming as Viola. So it was doubly comic and affecting to watch her frustration in trying to win the Duke's page for herself.

Fortunately, Viola's sea-wracked and presumed-lost brother, Sebastian [John Hansen], was every bit as handsome as she. In fact, although he is taller, in Helen Huang's elegant matching costumes, they really did resemble twins—as too often in productions of this comedy is not the case.

Although Shakespeare's Illyria—in set-designer Michael C. Smith's vision—could be somewhere in Morocco or any Ottoman-Occupied enclave, the presence of a priest indicated that Orsino had not succumbed to Islam.

The basic Elizabethan-Theatre stage-frame & facade was differenced, as is customary, by decorative details. The two posts upholding the Heavens over the stage were transformed into coconut palms.

And Huang's lovely costumes were especially and richly Middle Eastern. All that was missing was a camel or two.

The baiting and humiliation of Olivia's officious steward Malvolio [John Pribyl] seemed heavy-handed in the playing, making it also more cruel—and less comic—than usual. Director Timothy Bond might have made this less leaden.

Pribyl, however, was excellent in his prideful postures and crushed in his shaming. I am always bothered, however, by the vicious torment Shakespeare has devised for Malvolio when he is branded mad.

His incarceration in a dark chamber for presumed madness must have been hilarious to Elizabethan audiences. They of course could enjoy bulls and bears ripping each other to pieces near the Globe Theatre, so the sensibilities of the Groundlings were not so sharpened as ours today.

Ray Porter was a lusty Sir Toby Belch, identifying himself with a thunderous belch on his first appearance. Dan Donohue was a wistful delight as the timorous Sir Andrew Aguecheek. Quite a contrast with his King Henry V!

As Olivia's clown Feste—who also is available for other engagements in town—C. Valmont Thomas was a Presence. He helped hold the various threads of the plot together in a very genial and colorful manner. His mini-Feste finger-puppet was a special treat.

Curiously, the fate of the sea-captain Antonio—who for love of Sebastian risks purse and life—is left in limbo at the close. Arrested and under sentence of death, he just stands there among the otherwise happy throng. Finally, he seems to have been freed and wanders away.

But there ought to be, even in mime, some kind of resolution—glad or sad. There is—at least for modern audiences—a sub-text in his deep, if recent, affection for Sebastian, which mirrors the magnetism between Cesario and Orsino. Maybe this bothered director Timothy Bond?

"Your Own Thing" didn't miss a note on these confusions of love. If Ashland doesn't do it, some ensemble ought to produce the play and the musical in tandem. With the same casts. It would provide a provocative contrast.

The Taming of the Shrew—

| |

| TUTORING SESSION--Bianca [Tyler Layton] gets a lesson in love in "Taming of the Shrew." Photo: ©David Cooper, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

Even wise old Socrates was supposedly chained to a shrewish wife, Xantippe. No wonder he preferred to spend his time at the gym and in Athenian groves asking Socratic Questions of his circle of admiring young men.

With the Rise of Feminism and the proliferation of Women's Issues, it takes real courage for a director to revive this knockabout comedy version of the historic Battle Between the Sexes.

Even as Ashland audiences were laughing at the antics of the lusty Petruchio [Jonathan Adams], some of the women in the packed auditorium were not having such a good time.

Adams proves a very handsome and masculine woman-tamer, but his Katherina [Robynn Rodriguez] is an equally striking and powerful foil for his attentions. When she first sees Petruchio, there is a poignant silent moment when her eyes alone tell you she sees her Destiny before her.

And she doesn't welcome it. But she senses her entire life is about to change dramatically.

They are very well matched, and in some ways resemble the handsome and high-energy stars of the Broadway revival of "Kiss Me, Kate," Brian Stokes Mitchell and Marin Mazzie. They don't sing, but if they chose, an Ashland pairing of "Shrew" and "Kate" would—as with "Twelfth Night" and "Your Own Thing"—be stage dynamite!

John Pribyl, so effective as Malvolio, here makes a wonderfully wry clown as Petruchio's servant, Grumio. His best moment—after raging at length to a household servant to light a fire for his master—is his sudden deflation on being told the fire's already lit.

Sandy McCallum is hilarious as the pint-sized and aged suitor for Bianca's hand, Signor Gremio. He's obviously a good catch for Bianca [the lovely Tyler Layton], as his furious outbursts of temper will surely give him coronary arrest soon after they are married—leaving her a wealthy widow, free to choose her own husband or lover.

He trundles about the stage in a Renaissance version of a Walker, often running its wheels over the toes of Bianca's father. He even tries to mount its bottom rails to make himself taller.

Susan Mickey has devised some very handsome, even flamboyant costumes. Especially for the tailor, whose gown pleases not Petruchio.

Set & lighting designer Kent Dorsey has "differenced" the Elizabethan facade with some panels which seem digital enlargements of awkward illustrations of medieval life from some old manuscript. The idea is interesting, but I wasn't impressed with the visuals.

Director Kenneth Albers had the infelicitous idea of making the Christopher Sly Induction scene into an intrusive framework for the entire play. Whatever its appeal to Elizabethan audiences—including an opportunity for the principal clown to cavort—it can be cut without any major loss of impact to the real play.

Angus Bowmer at Ashland—like Richard Wagner's descendants at Bayreuth—never cut anything the Master wrote. So Albers may have had no choice.

But setting up the stage as a noisy tavern—with boisterous drunkards and brash pot-boys, who are enlisted to play roles in the play-within-the-play—slowed down the pace of the real action.

It was also strange to see a common inn presided over by a Lord of the Manor, who seemed to be entertaining a troupe of strolling actors in the manner of Hamlet at Elsinore Castle.

Sly became the fake father, Vincentio, but before that sea-change, he sipped or slumbered on the balcony-level of the stage. Ho hum.

As Tranio and Biondello, Kevin Kenerly and Julie Oda made a most amusing duo of fake master and real servant. How can such a big voice come out of such a tiny boy?

Hamlet—

| |

| GET THEE TO A MUMMERY!--The Player King [Ken Albers] mimes death, as Hamlet [Marco Barricelli] looks on in the Elizabethan Theatre production at Ashland. Photo: ©David Cooper, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

As a result, not many Bardolators got to see it. They can, however, have some idea of the Fiennes vision of the Royal Dane in Ashland.

Marco Barricelli—certainly a talent to watch—reminded me of Fiennes' star-turn. He also reminded me of the initial male-star of the musical, "Jekyll & Hyde."

He is handsome and larger than life. And super-charged with energy. No passion is small.

In his feigned madness, he wasn't safe to be near. No one, not even the innocent Ophelia [Diedrie Henry], was able to avoid his violent physical attentions. She was dashed to the floor. One feared for the actress's bones.

The lines Shakespeare drafted for his doomed hero seem most effective in manifesting Hamlet's rages and displeasures. Without recourse to man-handling the other actors.

In effect, a very Athletic Hamlet.

Unfortunately, some of the other actors, as characters, seemed pale by comparison. The effect was rather like a great Actor-Manager of the Victorian Era, dominating the stage while his hireling ensemble cower at the sides.

This impression was not dispelled by what passed for Danish Royalty. Laird Williamson's Claudius seemed mean and peevish, not at all kingly.

As John Barrymore once said: "He played the King as though he feared someone else would play the ace!"

Nor was Demetra Pittman persuasively regal as Queen Gertrude. Her presumed lust for Claudius and love for her troubled son also did not register as anything more than acting.

This would be unfortunate in any production of "Hamlet." But it is almost fatal when the King and Queen are opposed to a Force of Nature such as Marco Barricelli.

Obviously, this is only partly a problem of casting. A stronger directorial hand was needed to bring these forces into balance.

Or a different concept than that apparent in Libby Appel's production.

To my eye, there were also problems in staging some major moments. The Closet Scene—especially the placement of Polonius' dead body—was visually awkward.

The King and Queen sat enthroned, in isolated splendor on the balcony-level, for the playing of the "Mousetrap," the "Death of Gonzago," far below them. Like looking down on the heads of the actors.

As audience-attention was focused on the main-stage, front-and-center—despite Hamlet's urging us to observe the King's discomfort—Claudius's shattering outburst, "Give me some light!" was almost lost in the sudden confusion.

To compound the loss of visual and emotional power, instead of dashing off the balcony into a side-chamber, he clattered down the very narrow stairway at the stage-right of the stage-pavilion.

At its lower level, it was concealed by the post holding up the Heavens, obscuring what could have been a dramatic descent. He could even have tripped and tumbled down a much grander staircase, for greater effect. Like Talullah Bankhead in "The Eagle Has Two Heads."

But a similarly skinny staircase balanced this one on the other side, also diminishing effects of those climbing or descending on either side.

This design-decision was puzzling, for designer Richard L. Hay knows the potential of this stage better than anyone, having designed it and the entire canon of Shakespeare's dramas on it over the years.

He must have created this "differencing" of the standing facade to meet the needs of the production as envisioned by the director.

Appel is a much-admired director—as well as Artistic Director of the Festival—so this staging may conceal new interpretations and intuitions I simply did not understand.

In more than half-a-century of play-going, I have seen by now scores of "Hamlets." Many with the greatest interpreters of our age.

I must average two or three productions each season. Actors just won't leave the role alone.

So "Hamlet" is right up there, toward the top, on my list of Shakespearean plays I really don't have to see again. Including "As You Like It," Twelfth Night," "Midsummer Night's Dream," "The Scottish Play," and "Tempest."

Can that be why I was disappointed in this production? I seldom am at Ashland, where the standard is so high.

Old & New Classics in the Angus Bowmer Theatre:

Shakespeare's "Henry V"—

| |

| UNTO THE BREACH--The Siege of Harfleur in "Henry V" at Ashland. Photo: ©Jennifer Donahoe, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

Nothing gets lost, and the buffoonery makes earthy mock of the pretensions of the great and their royal mandates.

Appel has even underscored King Henry's own misgivings about the carnage of war and what his campaign in France will cost in human terms. In some deliberately "heroic" productions, this is quickly disposed of or cut.

Not here. But, once convinced of the divine rightness of his cause, Henry wages war with fury and passion.

When the count of battlefield dead is read, it's almost bitterly comical that so many French soldiers and so many great French nobles have perished in one day's warfare. And so very few English of any class.

In contrast to "Hamlet," the artful composition and dramatic dynamics of Appel's staging of major scenes in "Henry V" was most impressive. This was facilitated by designer William Bloodgood's bare-bones black-box quasi-factory setting.

Dull black stairs, balconies, and platforms served for most locations. Small glowing electric signs such as "French Court" and "Agincourt" kept the audience abreast of the rapidly moving action. Mistress Quickly and her tavern rascals were deployed down a staircase to great effect.

For the great Battle of Agincourt—instead of a confusing stage full of clattering pikes and swords—Appel and Bloodgood opted for an immense upstage mural of battle. This hung above a stage-wide reflecting surface, against which the combatants were frozen in a tableau vivant of ferocious fighting.

For important scenes during the progress of the battle, individuals stepped out of this human frieze to come downstage and do their thing. This was immensely effective, as was the long red cloth and the red curtain which signaled the end of this famous and bloody victory/defeat.

John Sipes was responsible for fight-choreography and movement. He got the same credits for "Hamlet," but this was much more powerful.

Dan Donohue's youthful King Henry paled beside some of his notable predecessors in the role. He could have been rallying his college team-mates to win the Big Game.

I wouldn't have followed him into battle, but his troops of vassals really didn't have much choice, did they? He was much more effective as Sir Andrew Aguecheek, in "Twelfth Night," but then no one would follow him into a fray.

Olivier's cinematic wooing of the French princess set a standard of charm, sex-appeal, and light comedy that few have since achieved. So it's no discredit to this Henry and Katherine [Susan Champion] that they tried to suggest a rapidly blooming sexual attraction in broken language. The Bard has set a real challenge to actors in the wooing scene.

It is an interesting idea to begin the drama with a single rehearsal-light on the bare stage. It fits the stripped-down production and indicates that the audience will have to use its imagination a lot.

To present the Chorus in the guise of an androgynous slim blonde in a long white coat took away some of the friendly authority with which Chorus customarily invites the spectators to warm up their imaginations.

This was further undercut by conflating Chorus with the Boy and the French Queen. This was very confusing, especially to some older viewers who did not know the play.

At least there was no danger in this production that eager young audience-members would rush to the stage to join Henry in his recovery of the great lands in France which belonged to his Angevin ancestors. The heroics were distinctly muted.

Euripides' "The Trojan Women"—

Unfortunately for those who'd like a preview, this production doesn't open until July 26. I was also sorry to miss it, for it has been designed by Richard Hoover.Steven Dietz's "Force of Nature"—

| |

| READY, AIM, FIRE!--Michael Elich, as Edward, prepares for a duel in "Force of Nature," by Steven Dietz, after Goethe. Photo: ©Charles Erickson, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

Dietz has adapted Johann Wolfgang Goethe's novella, "Elective Affinities," for the stage. He has also borrowed Tom Stoppard's framing-device from "Arcadia."

As this bitterly ironic German Romantic comedy opens, a group of friends gather in a spacious park for a festive photograph. The program says the time is The Present, but the costumes of Galina Solovyeva suggest the first decade of the century just past. Something like 1909?

Then the action shifts backward a century, to 1809. The ancestors of the characters we've just met now play out their destinies on the pastoral German estate of handsome Edward [Michael Elich] and lovely Charlotte [Robin Goodrin Nordli].

Edward may have been modeled by Goethe on Fürst Pückler, an eager world-traveler, one of the first Middle-Europeans to have written accounts of his adventures in strange lands and climes.

Prince Pückler—who is remembered today in Germany mainly for the ice-cream named after him—finally came home, married a rich woman, and settled down on his great estate, Schloss Branitz.

Here, he landscaped fantastic gardens and a lake with two pyramids on islands. He's buried in one of them. And there's a great tree trimmed to resemble an elephant.

Edward has also finally returned from endless travels. But he's still restless.

Not he, but Charlotte has landscaped the estate—which designer Richard Hay has subtly suggested resembles Ashland's valley-setting. She is so very anxious to please Edward—and keep him at home at last,

Her company is not stimulating enough for him, so he invites his dear friend, the Captain [Richard Elmore] to join them. Immediately, he and the Captain begin plans to flood the valley and Charlotte's landscaping—which the Captain finds amateurish.

The Garden, the Lake, the Dam, and other places or objects become visual metaphors for the demi-tragedies which are brought on by Edward's willfulness and the emotional chemistries which begin to develop.

A triangle of friends soon attracts a fourth affinity, the orphaned girl Charlotte should have adopted as her own child. Instead, she left Ottilie [Bridgette Loriaux] in a boarding-school.

When she is finally invited to the estate, Charlotte permits her to serve as a house-keeper, rather than as a member of the family. This only heightens her interest to the menfolk. For what it's worth, both Edward and the Captain have Otto for their first-names: Otto—Ottilie?

For all their faults, Goethe and Dietz's characters have a high sense of honor and of keeping up appearances. Whatever their lusts, no adultery is actually committed.

Indeed, most of the emotional activity seems given over to frustration, recrimination, remorse, and expiation.

This novella appeared as the Age of Enlightenment was waning. The French Revolution had shown where logic and reason could lead.

The Age of Romanticism—of which Goethe was the prophet and poet—celebrated the passions and needs of the individual over the communal good. It also invoked the unpredictable and untamable forces of Nature.

These are powerfully brought together in "Force of Nature." Is sudden passion like an unexpected flood? Could it have been dammed up before it unleashed its devastation on the innocent?

This is not a play for the easily amused. Like "Arcadia," it requires close attention and something like an "elective affinity" for the characters and theme.

Initially, I was not really interested in the problems of the peevishly proud Edward and the charming but clueless Charlotte.

Having just photographed the elaborate baroque gardens of Hannoverian Herrenhausen, however, I was interested in Charlotte's idea of a park. And I soon became interested—and angry, for Charlotte's sake—in the cavalier decision to flood the newly landscaped park with a lake.

The deviousness of her husband and the Captain in planning to drown all of her botanical tribute to Edward seemed cruel, indefensible. Especially as they had no intention to forewarning her of their plans.

Drowning her dreams is an obvious metaphor. But a climactic flood also drowns her great rival.

Goethe well understood the importance of Trust in human relationships, especially loving ones. But he could himself be as proud and selfish as Edward.

James Edmondson directed with elegance and sensitivity.

Tennessee Williams' "Night of the Iguana"—

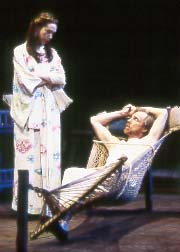

| |

| CRUCIFIED IN A HAMMOCK--Hannah Jelkes [Susanne Irving] regards the tied-up former minister Shannon [Richard Howard] with a cool eye in Ashland's "Night of the Iguana." Photo: ©Jennifer Donahoe, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

Andrea Frye is OK as Maxine Falk, the rowdy resort-hotel-keeper near Mexico's Acapulco. But she is certainly no Bette Davis.

Nor is Richard Howard a match for Patrick O'Neal, who created the role of the alcoholic and lusty de-frocked parson, Lawrence Shannon. O'Neal went on to open saloons and restaurants in Manhattan, such as the Ginger Man.

Howard should stick with the acting-craft. He has a spark and a passion. And Ashland already has enough pretentious eateries.

Howard's tortured Shannon was by turns hilarious, maddening, and pathetic. He was almost the best feature of this rambunctious staging by Penny Metropulos.

His contortions when tied into a center-stage hammock—arms bound to the cross-bar like a clothed Christ—did resemble those of the suffering Savior. But Shannon, in Williams' vision, is barely a man—and certainly not a god.

He cannot save himself, so he certainly cannot save others. And yet, when he encounters the endlessly traveling pastel-artiste Hannah Jelkes [Suzanne Irving], he experiences a moment of grace—especially when he frees the desperate Iguana, tied up for Maxine to eat.

As things fall out, Maxine will metaphorically—and maybe sexually—eat Shannon, but it's the end of the road for him, having seduced one too many under-aged girls, given into his charge on tours of Mexico.

Hannah—whom nothing human can disgust, unless it's cruel or vicious—is one of Williams' most affecting lonely ladies. Her devotion to her aged grandfather, the Nantucket poet Jonathan Coffin [Sandy McCallum], is especially touching.

Nearing the end of her rope, she's watching her Nonno near the end of his long life and his last poem. Not for nothing is he named Coffin. He ends his poem—and his life—on Maxine's verandah.

This is a serious comedy of rowdy passions and silent epiphanies.

Designer Richard L. Hay has very well recreated the oppressive tropical atmosphere of a more than slightly seedy Mexican resort.

Kaufman & Hart's "The Man Who Came To Dinner"—

| |

| TAKE YOUR TEMPERATURE?--Sherry Whiteside suffers Nurse Preen not gladly in Ashland's "The Man Who Came To Dinner." Photo: ©David Cooper, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

The New York Comedy of Insult—honed to razor-sharpness by decades of stand-up comics—may seem a bit quaint in the taunts invented for Woolcott/Whiteside by playwrights George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart.

But it's still amusing to hear his retort to the offer of a jar of calves-foot jelly: "Made from your own foot, I have no doubt!"

Ken Albers is both majestic and rascally as Whiteside, without doing an imitation of Monty Woolley in his signature-role. He is peremptory and perceptive.

But his needs, whims, and jests must first be served, before anyone else's are considered. Having injured himself in a fall on the front steps of the self-important Stanley Family on a mid-western lecture-tour, he takes over their house and their lives.

Considering the huge judgments now awarded in personal-injury cases, Whiteside's threatened law-suit against pompous Ernest Stanley seems comical in its now modest demands.

And many of the once instantly-recognizable personalities—who used to get a laugh merely by being mentioned—are now largely forgotten. Ghandi still gets a laugh. So does Banjo [Michael J. Hume], not necessarily because he's recognized as Harpo Marx, but because he's farcically funny.

As lovingly and frenetically revived by director Warner Shook—and designed in pre-World War II period by Michael Gannio [sets] and David Zinn [costumes]—this production is a bright, colorful tribute to the American Comedy of Manners of a more innocent time.

But then, Americans had manners then, even if some of them were threadbare and insincere. Oldsters in the audience—and Ashland is a magnet for Seniors—richly enjoyed themselves with this evocation of a past they can still recall. As can I.

Youngsters—of whom there are also a lot in Ashland audiences—seemed to find the farcical antics and bizarre quirks of character hilarious. The formulaic playing-out of the plot—complete with the Hollywood Vamp foiled by being locked in a golden Mummy Case—seemed a delightful resolution. Rather than purely authorial manipulation. TV has trained its audiences well!

The entire cast was excellent, but the finest moment, for me, was the entrance of the devastating Lorraine Sheldon [Judith-Marie Bergan] in her new Christmas outfit. David Zinn had confected a bright red-and-green Christmas Tree dress and hat for her!

This is a production which should delight Broadway audiences. If they came to Ashland, they would love it.

But on Broadway, without familiar names or TV personalities, it might easily be dismissed—by some critics, at least—as provincial or well-intentioned amateur. Not so!

Drama in the Black Swan—

Margaret Edson's "Wit"

| |

| NOT YET DONE WITH DONNE--Dr. Vivian Baring [Linda Alper] confronts death in reality, not only in poetry, in Margaret Edson's "Wit." Photo: ©David Cooper, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

So I already have a clear idea of "my" Dr. Vivian Bearing, the fiercely academic John Donne scholar. And cancer victim.

What is perhaps most amazing about Margaret Edson's brilliant play is that no one saw that brilliance when the script first made the rounds of almost every regional theatre and New York producer. In some cases, it was rejected not once, but twice or even three times.

Only Manhattan's MCC Off-off-Broadway production-group realized its potential. The rest is theatre-history. "Wit" is now being played on major stages world-wide.

Linda Alper, Ashland's Dr. Bearing, is certainly fierce and tough, but her hard edges don't seem so gem-like and subtly cutting as Chalfant's. She seems a bit more like a diamond in the rough.

Nonetheless, she is able to mine the vein of ironic comedy, as well as the well of loneliness. She fights back her tears, but the audience cannot.

Dr. Bearing knows a lot about the idea of Death and Mourning, thanks to her close analysis of the religious poetry of John Donne. She even has learned, at some cost, what a comma or a semi-colon can do to change the meaning of a poetic sentence.

What she has not learned is how to be humane—even to be human—to herself and her students. Her adamant insistence on only the highest standards of scholarship turn away average students—who might have learned much from both Donne and a caring professor.

Deidrie Henry is wonderful as the sympathetic nurse who prevents Dr. Baring's physicians from prolonging her torment only for the purposes of medical observation. And that possible paper in a medical journal.

In an odd way, there's a parallel, as Baring has herself been extremely clinical in dissecting Donne's poetry and her students' essays.

William Bloodgood designed elemental hospital decor and provided basic medical props. Costumer Claudia Everett also had her work cut out for her, considering the action of the play.

Director John Dillon moved the play along briskly.

Lynn Nottage's "Crumbs from the Table of Joy"

| |

| SEX AND POLITICS--Aunt Lily is a Harlem Communist and red-hot mama, in Lynn Nottage's "Crumbs from the Table of Joy." Photo: ©Jennifer Donahoe, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

[For that matter, how many realize that the Rev. Sung Myung Moon has proclaimed himself Christ in His Second Coming?]

At least Father Divine didn't make his followers move to Jonestown and drink poisoned Kool-Aid.

Instead, in his "Heavens," his people were invited to feast on fried-chicken, grits, gravy, and yams. And they weren't only the disenfranchised blacks of the inner cities.

At Father Divine's Heavens, All were welcomed. These were among the very few places where whites and blacks could mingle in friendship and worship before the Second World War. And for some years after, as well.

Lynn Nottage's young black heroine, Ernestine Crump [delightfully played by Melany Bell], not only has to live with a grieving father who is slavishly devoted to Father Divine. But she also soon has to deal with a new white step-mother he's met on the subway and taken to Father Divine's Harlem Heaven.

The new Mrs. Crump, Grete [Elizabeth Norment], is not only white, but also a penniless immigrant from a shattered postwar Germany.

Life at home is complicated by the flamboyant presence of Ernestine's and her younger sister Ermina's aunt, sister to their dead mother. And a self-confessed candidate for replacement wife and mother.

Lily Ann Green [BW Gonzalez], despite her name, is really a flaming Red, notorious in Harlem. And not only for her politics.

Rumors of these revolutionary ambitions harm the simple country-boy Godfrey Crump [Tyrone Wilson] at the bakery where he works in Brooklyn. He's from Florida, where his lack of education and elemental intelligence have severely limited him.

The move North has been a physical and spiritual dislocation for him and his daughters. All his problems he writes down on little scraps of paper for Father Divine to answer for him when the great Father finally comes to dinner. Which of course he never does.

Although the fears, heartaches, and humiliations of father, aunt, and step-mother are potent, even pathetic, dramatic material, this basically a Coming-of-Age play.

Ernestine narrates explanatory passages between brief but arresting scenes. This enables Nottage to cover a lot of territory. It also allows Ernestine to ponder what is happening to her, as well as to her elders.

One of the most engaging aspects of the drama is the playing-out of scenes Ernestine wishes had happened in their shabby apartment. As in the meal at which Grete sheds her dressing-gown to reveal a Marlene Dietrich persona—complete with silk undies and top-hat—dancing on the table and singing "Falling in love again, can't help it."

Director Seret Scott brings all these diverse stylistic and human elements together in an affecting portrait of a Family in Transition and a Girl Growing Up.

Diana Son's "Stop/Kiss"

This most affecting drama of young female friendship is opening July 4, so I did not get to see the production. Nonetheless, it was reviewed in this column when it was premiered at New York's Public Theatre.Preview of Coming Attractions—

Although the 2001 Ashland Season begins, as customary, in February, next July promises to be a very busy month. The American Theatre Critics Association will descend on its three theatres in force.This is the American critics' second visit to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. After recommending Ashland's chief arts-industry for a Tony Award in 1983—which was duly awarded and appreciated—the group came to see what they had praised in advance.

Actually, Richard Coe, of the Washington Post; the San Francisco Chronicle critic; yours truly—who has been coming to Ashland for many, many seasons, and Al Reiss, who then covered the arts in Southern Oregon, were all eager advocates of the Tony for this remarkable festival.

Al Reiss is "coming out of retirement" to once again help plan a wonderful week for us critics. With a possible side-bar of Oregon sight-seeing. The beautiful Southern Oregon Coast was a highlight of our last group-visit.

What all this means for the general public—and you, if you are planning a visit to Ashland—is that tickets will be tight in mid-July. But you might just have the opportunity to meet and chat with some of America's leading theatre-critics.

Here's the projected program for the real Millennial Year, 2001:

The Elizabethan Theatre:

THE MERCHANT OF VENICETROILUS & CRESSIDA

THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

The Black Swan:

THE TRIP TO BOUNTIFUL—Horton Foote's modern American Classic.FUDDY MEERS—David Lindsay-Abaire's admired and slightly surreal drama, shown this season at the Manhattan Theatre Club and reviewed in this column.

TWO SISTERS AND A PIANO—Nilo Cruz's sweetly sad nocturne on life in Castro's Cuba, shown at the Public Theatre this season and reviewed in this column.

The Angus Bowmer Theatre:

THE TEMPEST—The Bard indoors, where the rains of summer cannot fall.LIFE IS A DREAM—Calderon de la Barca's Siglo d'Oro Dream-Play.

THREE SISTERS—Anton Chekhov's classic of sibling solidarity, staged by Festival Artistic Director Libby Appel.

ENTER THE GUARDSMAN—a new musical, based on Ferenc' Molnar's boulevard comedy, The Guardsman, just showcased in Manhattan this season and reviewed in this column.

OO-BLA-DEE—a new prize-winning drama by Regina Taylor, recently honored by the American Theatre Critics Association.

Ashland's New Fourth Theatre—

| |

| MODEL THEATRE--Mock-up of the new playhouse for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. Photo: ©Jennifer Donahoe, 2000/Oreogon Shakespeare Festival. | |

But the outdoor Elizabethan, the Swan, and the Bowmer will soon have a younger sister. This is the new indoor theatre, set on a parking lot between and behind the scene-shop and Carpenter Hall.

The primary reason for its construction are the severe limitations of the Black Swan—which cannot be enlarged. Frequently, its productions are among the most in demand of the entire festival repertory. But it seats only 138—less than Off-Broadway theatres, which have a 299-seat limit.

The new theatre, which will open in 2002, will seat from 260 to 360, depending upon its seating-conformations for each show.

The design of the theatre, outside and in, is the result consultations with the City Council, the architects, and of open community forums. Significant adjustments have been made to please those who live near the theatre, as well as vigilant Ashland citizens who want to protect the somewhat Victorian small-town character of their handsome city.

The Black Swan will continue in use for play-readings, lectures, and rehearsals. Carpenter Hall will be available to the community for various cultural uses.

The development over the years of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival—purely in terms of its real-estate and professional theatres and shops—is astonishing. That its production standards are also thoroughly professional has been attested by the Tony Award.

I used to sign-off Ashland reports with the observation that these achievements are amazing in a small town in the "middle of nowhere." Several years ago, some proud Oregonians pointed out to me that the Rogue River Valley is definitely not in the middle of nowhere. [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home |

listings |

columnists |

reviews |

what's new? |

cue-to-cue |

people |

welcome |

| museums |

recordings |

what's cool? |

who's hot? |

coupons |

publications |

classified |