GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, May 3, 2000

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] "What You Get and What You Expect"

[03] "Yard Gal"

[04] "The Ride Down Mount Morgan"

[05] "Our Lady of Sligo"

[06] "Copenhagen"

[07] "Moving Bodies"

[08] "The Five Hysterical Girls Theorem"

[09] "The Waverly Gallery"

[10] "Rose"

[11] "House Arrest"

[12] "The Real Thing"

[13] "Suite in Two Keys"

[14] "The Lucky Chance"

[15] "Uncle Vanya"

[16] "Naked"

[17] "Miss Lulu Bett"

[18] "Hotel Universe"

[19] "Balloon"

[20] "The Green Bird"

[21] "The Music Man"

[22] "Jesus Christ Superstar"

[23] "Aida"

[24] "The Donkey Show"

[25] MTC "Wild Party" I

[26] Public "Wild Party " II

[27] "Platée"

[28] "La Clemenza di Tito"

[29] "Il Matrimonio Segreto"

[30] "Der Kuhhandel"

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

Plays Old & New—

The "Theatre Season" isn't quite over yet. It used to end officially on May 31st. Now, with shows in Central Park and other venues, it drags on and on.This July, however, will be anything but a drag. From July 11 through the 30th, the Lincoln Center Festival will offer a wide range of dance, opera, theatre, and musical events. Two major Moscow theatre companies will perform. A Dutch opera, "Writing to Vermeer," will certainly astonish.

For more information and booking, phone: 212-875-5030. If you can read this, you can click on Lincoln Center Festival 2000 on their website: www.lincolncenter.org

But the current season of new and important openings might as well be regarded as at an end. All the important pending Broadway productions—excepting "Taller Than a Dwarf," which was having serious problems—managed to open before the major awards-nominations.

As I'm a nominator for the Outer Critics Circle Awards—and a voter for the Drama Desk Awards—at this point, I've seen them all. Except the Dwarf-Play.

So this column will be a brief round-up of what opened in April, before I begin my journeys to festivals East and West, American and European. Some of these shows will no longer be playing by the time you read this, but they are included either because the plays themselves are worth knowing. Or their productions were so interesting that the talents involved deserve mention.

"What You Get and What You Expect [****]

This title is cart-before-the-horse. Very French! Americans more often reverse the formula: "What you hope for—and what you actually get."Jean-Marie Besset's admonitory satire suggests this French playwright as an avant-garde descendant of Molière. He's even won the Molière Award, the Parisian equivalent of a Tony.

He is certainly a talent whose work should become better known here. And it's instructive that the New York Theatre Workshop has had the vision to mount this impressive production, staged by Christopher Ashley.

The late President Mitterand's Grand Projects for making Paris even more architecturally overwhelming—with a Post-Modernist cutting-edge—are the inspiration for this fable of true talent vs. double-dealing and slick diplomacy.

Mitterand's over-reaching ambitions are mocked in this bitter comedy. The architectural competition which sets this fable in motion is the proposal to build a Monument on the Moon.

The President wished to be remembered—as did Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin—with grand, overpowering structures, emblematic of the Historic Glory of France. Only now do we discover that the Grand Theatre in Lyon has had to be shut down because of defects in its historical restoration.

Mitterand's grand Arche de la Defénse—with offices inside its glass-walled cube-with-a-square-hole-in-it—extends infinitely the perspective from the Champs Elysées through the Arc de Triomphe and beyond.

We have also recently learned that Mitterand offered Germany's former Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, an impressive bribe—which he eagerly but secretly accepted

Similar slimy policies also inform the process of selecting the prize-winning project for the Moon Monument.

Stunningly clothed and groomed, Pamela Payton-Wright was intimidating as Louise Ekranter, the government official who can make things happen for the right candidate.

Stephen Caffrey played the baffled architect Phillipe—too long away in Africa and unwise in the mazes of Parisian intrigue. Peter Jacobson was Robert, his architectural antagonist and thief of his design-concept.

Robert knows his way around the grand corridors of Parisian Power. He's fucking Mme. Ekranter. We even got to see them in action on a desk.

To add a French frisson to the plot, there's also the unresolved issue of the mutual attraction in school-days of Phillipe and Pericles, another ministerial functionary. Daniel Gerroll was, as usual, urbane as Pericles' lover of convenience. He also beds Phillipe's wife. Very French!

Klara Zieglerova's imposing setting was elementally minimalist, except for two immense upstage doors. Closed—and seldom opened—they said it all.

Rebecca Prichard's "Yard Gal" [***]

This elemental but powerful production—staged by Gemma Bodinetz—comes to Manhattan's MCC Theatre from London's Royal Court. With some delay, as it was originally mounted in the Court's Theatre Upstairs in 1998.Although the two vagrant teen-age druggies, Boo and Marie, have a wild and violent story to tell, this is not exactly unexplored territory. Nor are these lives unfamiliar, even though the two girls are growing up absurd in London's Hackney "housing-estates."

On a bare stage—except for four illuminated boxes which contain all the needed props—the girls tell their ferocious story of black and white bonding in the urban jungles of East London. But the theatre-event is more like Story Theatre, with various adventures and disasters acted out in this catalogue of horrors.

It's not the material, nor its form, that's impressive in this show. In fact, they are both off-putting—for different reasons. No, the power of the production comes entirely from the acting of Sharon Duncan-Brewster as the bold, brave, black Boo and Amelia Lowdell as the softer, more ambiguous, white Marie. These are talents to watch!

When I arrived at MCC, shortly before curtain, there was almost no one in the lobby. A warning on the wall advised that strong language would be used. Living in New York and walking its mean streets, I find this no problem. What could surely have turned off the MCC's indulgent and prosperous patrons were the horrendous details of the gang-lives of these girls and their peers.

Three Shown in London before New York:

If someone unearths a forgotten Restoration Comedy which has never before been done in Manhattan—and there are a number of them in the British Library—of course it will be featured as a "New York Premiere." Three-hundred years after the London premiere!Just because the three plays immediately below have not been produced before in New York doesn't mean they are all that new. The latter two are fairly new, however.

But I saw Arthur Miller's "Ride Down Mount Morgan" almost a decade ago in London, at Wyndham's Theatre. There, actor Tom Conti—who had played the hero of "Whose Life Is It Anyway?" on Broadway in a cast up to his neck—was lying in a hospital-bed in a cast up to his neck,

I suggested to him that Miller's play should therefore be renamed: "Whose Wife Is It Anyway?"

Arthur Miller's "Ride Down Mount Morgan" [***]

The idea of Bigamy as an absorbing dramatic—even comic—situation is not exactly a novelty in the theatre. At the cinema, it has also proved its potential, as in "The Captain's Paradise."Or at the opera—as witness "Platée," recently staged by Mark Morris for the New York City Opera. In this frolicsome work, Juno's husband Jupiter is planning at least a mock marriage to a slimy swamp-creature—who thinks she's a great beauty.

Bigamy can be big-time entertainment. In fact, I just found a provocative entry in my very own Chronology of Twentieth Century British and American Theatre—now being put online by the NYU Data Center:

"Dec 22, 1937: The debonair British revue & musical-comedy star, Jack Buchanan, opens on Broadway at the Imperial Theatre in Between the Devil." The show is the handiwork of Howard Dietz & Arthur Schwartz. Buchanan plays a husband with wives in both London and Paris."

Arthur Miller has now had productions of "Mount Morgan" in both London and New York. But that's not quite bigamy.

It says something about the cautiousness of producers that it has taken such a long time for the play to reach Broadway. It was even recently tried out down at the Public Theatre—testing the audience-temperature, perhaps?

Now at the Ambassador Theatre, on Broadway at last, the play betrays some dramatic tinkering. Miller has updated the London version with cell-phones and frequent uses of the F-word and its variations.

But it's a bit sad to see America's Greatest Living Playwright, in his advanced seniority, somewhat obsessed with sex.

This isn't exactly the male version of "The Vagina Monologues," but it comes close. Worshipping at the shrine of a "pink cathedral" is an image that Miller's "The Crucible" was spared. Though that drama's protagonist was also undone by adultery.

Awash in Miller's Moral Concerns, we may have overlooked—or forgotten—how central male-female sexual relationships have been to a number of his dramas: "After the Fall," "Broken Glass," "Death of a Salesman."

Willy Loman's shabby infidelity was the trigger for Biff's self-destructive self-discovery: the sexual worm at the core of the American Dream Apple!

In an odd way, however—as played by the vigorous, but graying, Patrick Stewart and staged by David Esbjornson—the current production is in danger of becoming a laff-riot.

Unlike Tom Conti, Stewart is not in a cast, so he is more agile, even in a hospital-bed. And he's a charming devil-of-a-fellow! Women in the audience may forgive him everything in his search for "the better hole."

Men may envy him, considering the almost comic contrast between his uptight first wife [Frances Conroy] and his sexy second [Katy Selverstone].

Nonetheless, despite a much more powerful and visually interesting production than the play had long ago in London, I still find the material and its treatment neither moving nor amusing.

The idea of the near-fatal, crippling ride down Mount Morgan could have been borrowed from Edith Wharton's New England novel & drama, "Ethan Frome." But Ethan and Mattie Silver did it on a sled. Not in a trendy auto.

Sebastian Barry's "Our Lady of Sligo" [****]

Max Stafford-Clark originally staged this arresting drama of social & personal loss—in the wake of Irish Independence—for Out of Joint & the Royal National Theatre in London. So it's new to New York at least.Barry recently had a small success in New York with "The Steward of Christendom." Considering the current flurry of interest in young Irish playwrights, more of Barry's dramas deserve production here, as well as "Our Lady of Sligo."

Strongly staged and acted at the Irish Rep, this show deserves a wider audience and a longer run than is possible in Off-Broadway institutional theatre. But can it transfer?

As it focuses on a bitter, chronic-alcoholic woman, now painfully dying of cancer in a Dublin hospital, it might seem too strong for audiences who have already had their cancer-play with "Wit!"

Her marriage was a long-term, hateful battle-of-the-sexes. Even for dysfunctional Irish families, Mai and Jack stand out.

But Mai is played by the dynamic and marvelously talented Sinéad Cusack—who should be on Broadway. On the sickbed that will shortly become her deathbed, Mai recalls her curiously blighted life—which began with such great expectations.

This is not, however, a monologue with interludes—though Barry's structure comes close to that. Mai has a sympathetic Roman Catholic nurse [Andrea Irvine] at her side.

And her well-dressed Dada [Tom Lacy], as well as her sharp, well-tailored, British officer & engineer husband [Jarlath Conroy], appear at her bedside to relive both the hopeful and horrible events of their lives.

What lifts these memories above the TV soap-opera commonplace is Barry's remarkable Irish poetic gift. Mai is especially endowed with a facility for describing joy, boredom, loathing, and pain in some wonderfully perceptive images and similes.

Mai and Jack's tragedy is to have lived the wrong lives—at the wrong time.

Even though Roman Catholic Native Irish, they aspired to the social graces and customs of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. This was swept away by Irish Independence, after which all things English or British were anathema.

The antipathy of the Irish Free State—and, later, the nation of Eire—against Britain was such that Prime Minister Eamon de Valera delivered a Note of Condolence to the German Embassy on the death of Adolf Hitler!

Barry Footnote: Sebastian Barry has just written the book for the new Frank Loesser stage-musical, "Hans Christian Andersen." This will have its world premiere at San Francisco's ACT in the autumn.

To be staged by the ingenious and innovative Martha Clarke, the new show's songs have been borrowed from the Danny Kaye film of 1952. The talented composer Richard Peaslee has adapted Loesser's music to create a complete musical score. He and Clarke have worked together on several impressive productions, including "Miracolo d'Amore"—one of my all-time favorites.

The Aborted Evening Walk:

Michael Frayn's "Copenhagen" [*****]

| |

| "COPENHAGEN"——Three's a cast in Michael Frayne's drama about two famous physicists: Philip Bosco, Michael Cumpsty, Blair Brown. Photo: ©—Joan Marcus/2000. | |

As the distinguished Danish physicist, Niels Bohr, Philip Bosco is both a dedicated scientist and a sensitive human-being. And Blair Brown—as his very intelligent and wary wife—is a wonderful mediator between him and an unexpected, even unwelcome, visitor to Nazi-Occupied Copenhagen, early in World War II.

Michael Cumpsty projects the vigorous but ambiguous persona of a super-bright former acolyte and virtual son, later colleague and friend, and finally the man who could help the Nazis build an atomic bomb.

This character is atomic physicist Werner Heisenberg, the articulator of the now fabled "Uncertainty Principle." And there is a great deal of Uncertainty in this play—in the minds of the Bohrs, possibly even in Heisenberg, and certainly in the minds of the audience—about the reason for his sudden appearance in Copenhagen.

Is he trying to find out from Bohr what progress the Allies are making toward developing a super-weapon to defeat the Nazis? Is he looking for guidance, for approval even, of the researches he is making in Germany?

Is he uncertain about how far a scientist should go, even when the future of his own beloved country is at stake? Is he trying to avoid discovery of the Ultimate Weapon, for the sake of humanity?

Almost as in "Rashomon," the meeting and the aborted evening walk outside—where Nazi mini-microphones cannot follow—are replayed from the three points of view. But playwright Michael Frayne and his able director, Michael Blakemore, leave audiences intentionally uncertain regarding intentions and deeper meanings.

In the play, it's noted that postwar British Occupation authorities bring Heisenberg again into confrontation with Bohr, returned to Denmark from his escape into exile, helping the Americans develop the atomic-bomb.

It's implied, however, that their friendship and father/son relationship came to an end on that brief evening walk. It makes a powerful human moment.

In fact, both men—and other surviving atomic physicists of that era—met cordially after the war for several summers of symposia in the medieval town of Lindau on Lake Constance.

I know this only because my good friend, Dr. Beata Bennett, has shown me the photo-album she made of those summers, with snapshots she took of Bohr, Heisenberg, and other greats. As a little girl, Beata Hein, she was a favorite of these monumental figures, who had been invited to Lindau by her father.

A medical-doctor and professor at Munich's Ruprecht Carolus University, he refused to join the Nazi Party and so was dismissed from his professorship. He went into internal exile, spending the rest of his life as a doctor in Lindau.

But he had the respect of these great men, so they were glad of the opportunity to meet again in comparative isolation and anonymity.

Dr. Bennett took her album to the recent CUNY Grad Center symposium on "Copenhagen." She showed it to Michael Frayn, but he pointed out that his version of the Bohr-Heisenberg relationship made a stronger play.

So much for Happy Endings! But at least Heisenberg never made an atomic bomb.

Atomic Physics on This Side of the Atlantic:

Arthur Giron's "Moving Bodies" [****]

Neils Bohr was partly Jewish—not "the whole thing," as Jonathan Miller would say. Arthur Giron's manic and lovable American mathematician-physicist, Richard Feynman [Chris Ceraso], is more than the whole thing: he's a New York Metropolitan Jew. But, like Werner Heisenberg, he's also superbright and fascinated by the solution of intricate equations. His role in the development of the atomic bomb is central to Giron's play, but it is also very much about human loves and losses, in pursuit of scientific truths and more dubious goals.

He's finally the whistle-blower—although a dying man—in the official enquiry into the fatal explosion at the rocket-launch of the NASA Challenger.

This, audiences may recall from seeing it on television, occurred in full sight of President Ronald Reagan and the family of the unfortunate young school-teacher—who died hooribly in a disaster that need never have happened.

Feynman reveals to the press—with a very simple demonstration—why and how the Challenger blew up. Horrified officials try to stop him.

But Giron's drama is also about upper-class and official anti-semitism, which for so many years prevented many able, talented, educated Jews from taking their rightful place in the professions and adminstrative positions.

Giron is a wise, compassionate, and skilled playwright. All of his plays are fundamentally concerned with man's striving toward the stars. And with the forces which conspire to prevent achievement.

Arthur Giron has even taught playwriting at Carnegie-Mellon. He knows the theatre and American drama very well indeed.

But I do not know if he intentionally drew on period models of playwriting for the earlier events of his drama, which spans the years 1933 to 1986.

We first meet the entire Feynman Family in a car made of chairs. With young Richard at the wheel, driving them off to Chicago's Century of Progress '33 World's Fair.

This is right out of Thornton Wilder's "The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden." I recognized the similarities because it was the first play I ever directed: short text, no sets, and small cast.

As Dick goes to college—joining a Jewish fraternity, not great, not gentile Sigma Chi, but a notch upward, not like sleeping in a dorm—the dialogue seems modeled on Clifford Odets: "Life shouldn't be printed on dollar-bills!"

These and other period resonances may not be intentional, but even if they are subliminal, they are altogether appropriate.

Feynman didn't have Niels Bohr for a mentor, but he didn't do badly. His preceptor and occasional protector proves to be none other than pipe-sucking J. Robert Oppenheimer [Robert Boardman].

I remember this distinctive, contemplative figure—always with pipe and pork-pie hat—on campus at UC/Berkeley. "Oppy" lectured to us undergrads on physics and the scientist's responsibility in the modern world.

And then his nemesis, Dr. Edward Teller, another UC physics prof, discredited him and prevented further access to atomic experiments at the Los Alamos labs, which long remained an out-of-state campus of the University of California.

Oppenheimer was viewed as a security risk, through his wife and his acquaintance with French professpr, Haakon Chevalier. Those were the dark days of McCarthy and incessant witch-hunts.

Giron's drama recalls the human price to be paid—on the most personal levels—when theoretical science has to be put to "practical" uses. When scientific truth and plain common-sense are ignored so special and questionable political agendas can be pushed.

Chris Smith directed the able cast with a dynamism that made up for the minimalist setting at the Ensemble Studio Theatre.

"The Five Hysterical Girls Theorem" [**]

Those who may have been daunted by brisk discussions of particle physics in "Copenhagen"—or of complex mathematics hinted at in "Moving Bodies"—will be positively baffled by Target Margin's world premiere of Rinne Groff's new theoretical satire. It's briefly on view at the Connolly Theatre, between Avenues A & B, on East Fourth.Its tortured text makes the physics in "Copenhagen" seem as simple as short-division. In this show, explorations of, and discoveries about, Prime Numbers are apparently the focus of what may be some kind of turn-of-the-century Mathematics Congress.

Or the occasion may be a Valedictory Lecture, a Grand Summation, by a famous mathematical theorist—who seems to have plagiarized the discoveries and equations of a would-be acolyte.

One of the Late Victorian girls in this professor's household is frequently and furiously inscribing complex numbers-series on doors and back-walls. At one point, she adds a large-scale graffito to the rear wall: The Veronese Brothers Suck Donkeys.

The trio of Veroneses is balanced by a threesome of mad Russian mathematicians, all of whom are named Nikolai Nilolaiovitch. The apparent protagonist, Professor Moses Vazsonyl, has a wife and daughters: Sophie, Vera, Hypatia, and Kleine Esther. But they add up to only four hysterical women.

This peculiar and highly hermetic parody did not yield up its inner mysteries to me. But I must give full credit to the dynamic Actors' Equity cast—all of whom seem totally dedicated to the sometimes brilliant, but often bizarre, directorial aesthetic of Target Margin's founder & director, David Herskovits.

Still, I wouldn't want to miss one of their productions. Their stagings of Julian Green's "South" and the Heyward's "Mamba's Daughters" were innovative and impressive.

Alzheimer's in the Village:

Kenneth Lonergan's "The Waverly Gallery" [***]

On the M104 bus down Broadway, after seeing "The Waverly Gallery" at the Promenade Theatre, I was astonished to overhear two older ladies clucking with feigned sympathy. They were dissing the performance of that grand old trouper, Eileen Heckart, now over 80 years old. "Did you hear how often she blew her lines? She couldn't seem to get them right!"

Two hours of Kenneth Lonergan's painful play about an old lady with Alzheimer's—and her caring but desperate family—seemed to have missed its mark with these hardened Golden-Ager theatre-veterans.

Heckart is both lovable and pathetic, amusing and irritating, as an aged Greenwich Village art-gallery proprietor, who is losing her grip on reality, memory, and self-control.

She's surely not fluffing her lines.

Although I've not seen the script, that must be the way Lonergan has transcribed the gradual descent of a once alert, bright, and clever lady into a misty world of memories and increasingly impeded communication with those who love her.

My own father—before they had a name for this destructive malady—spent six years in a living limbo. As in Lonergan's drama—which does have some laughs, at least—his memories were scattered and strangely inter-connected.

He finally had to be cared for like a baby by my mother, who rather savored such a martyrdom. After all, she had treated him so badly when he was still in his right mind.

She told me the Vets' Hospital refused to take him. Later, I learned that wasn't true. She simply didn't want the neighbors saying she'd put him away.

I was on a photography-jaunt to Guatemala and woke up in the middle of the night with a very strange feeling that something was wrong out in California. But I called her only when I returned to New York.

"Where were you? I waited a week for you to bury your father!"

She knew where I was, but she neither phoned nor cabled. She expected that I would know when he died, without being told.

Shortly after, she began her own eight-year Alzheimer's living-death. Neither my father nor my mother recognized any of the relatives, friends, or care-givers. They were all called by names of people long dead.

Strangely enough, I was the only person either of them recognized to the end. Even though I lived on the opposite coast and could come West only twice a year. Indeed, my mother thought I was sharing meals every day with her in the Santa Paula rest-home where she lived out her days.

So I found Heckart and her play very affecting. As I'm sure many, many people of all ages will, either in performance or reading. This may be too painful for some—especially families who feel trapped in such situations—but it could also be an odd kind of therapy as well.

Monodramas—

Creating a detailed stage-milieu for what is essentially a monologue suggests not so much actual, useful, relevant scenery as the producers' lack of faith in the material and the performer. Both the monodramas below could stand on the strengths of their texts and stars.Olympia Dukakis in "Rose" [****]

| |

| ROSE ROSE——Olympia Dukakis as a Holocaust survivor in Martin Sherman's monologue. Photo: ©—Lalas Sakis/2000. | |

She has escaped the Nazis and reached Palestine. But no sooner than she's kissed the soil—unlike the Pope—she's hustled back on the rusted refugee-ship. The British troops protecting the Palestine Mandate have quotas to enforce on would-be Jewish immigrants.

A young American Zionist saves her from being transported to the Death Camps. She marries him and becomes Rose Rose!

The growing emotional division between dedicated American Zionist supporters of the State of Israel and the younger natives growing up there is a source of some pain to the aging Rose, now a prosperous hotel-owner in Miami.

But why go on? You can get all this, and more, from watching or reading "Rose."

Director Nancy Meckler could have made the visual aspects more interesting had she devised ways for Dukakis/Rose to move about in her South Florida home. Rose seemed rooted to her center-stage perch.

Anna Deavere Smith in "House Arrest" [***]

Among previous triumphs of this National Treasure-quality artist are two shows based on extensive interviews with people intimately involved with major urban crises in Brooklyn and the City of Angels: "Fires in the Mirror" and "Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992."These insightful interviews Deavere Smith deftly edited, interwove, and then performed. She wonderfully suggested the speech-patterns, gestures, and thought-processes of her subjects.

She has done it again in "House Arrest," at the Public Theatre. But this material has been developed through several transformations, including being performed by a cast of actors, not solo.

The title indicates Smith's general concept: that the elected Occupant of the White House is, in effect, under house-arrest. The eyes of the media—and of the world—are always upon him.

He has almost no privacy, no quiet-time. He cannot walk anonymously through the late-night streets of Washington. Not even in disguise, as Caliph Haroun al-Rashid used to do long ago in Baghdad.

[Today, of course, it's not a good idea to be in Baghdad at all, day or night!]

While this new show is entirely enjoyable and interesting, it seems a bit unsure in its structure, materials, and presentation.

Obviously, the entire evening cannot be spent in the White House.

But quite a bit of time is spent down in Virginia on Massa Tom's plantation, Monticello. The Sally Hemmings Story, which Deavere Smith exhumes, could well be an evening in itself. And it stands apart, in place and time, from most of the material.

True, we do pay a visit to Abe Lincoln, but it is Washington-centered.

It would have been fun to have Smith take us to the White House to watch Jackie "O" redecorate it, followed by the taste-changes of Lady Bird Johnson and Nancy Reagan. Not weighty enough?

Unfortunately, Smith had to depend on journalists, columnists, commentators, insiders, lawyers, and officials for much of her information, evidence, and opinion about Presidents and other politicians.

These smug opinion-makers seem often less interesting, less honest, less authentic, than the real people Smith has interviewed in America's great ghettos.

Deavere Smith has proved a powerful performer with no more than a baseball cap, a pipe, and some hand-props. In "House Arrest," however, she has a series of suggestive settings glide in and out—designed by the talented Richard Hudson—and she has a number of elaborate costume-changes.

These "production-values" may be regarded as necessary to hold audience-interest. But I found them a distraction—and certainly a delaying tactic—from the various impersonations.

An Excess of Revivals—

Scores of new American plays continue to have plain readings, staged-readings, and even workshops in New York and across the nation. What most of them never achieve is an actual production on or Off-Broadway.For many of them, there are several very good reasons for this: they aren't interesting, insightful, original, innovative, or even amusing.

But there are others—outstanding scripts, such as "Wit!—which are repeatedly rejected by nervous producers. Some potentially exciting plays never find the right agent, dramaturg, or producer.

So we fall back on proven successes of yesteryear, hoping the magic will work once more.

Tom Stoppard's "The Real Thing" [****]

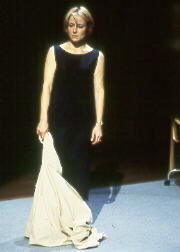

| |

| JENNIFER EHLE IS THE REAL THING——As seen in Tom Stoppard's drama of love and infidelity. Photo: ©—Ivan Kincel/2000. | |

That's not such a bad thing. As the actors are moved about in the cubic space by director David Leveaux, the changing compositions are a form of art in themselves.

But they are as impermanent and precarious as the house of cards the playwright-within-the-play [Stephen Dillane] builds on his coffee-table and in his actual script of the relationships among a young actor, a playwright, and his actress-wife.

Did she deceive him? Did he, in a way, provoke or permit adultery?

This witty drama is neither "Rashomon" nor "Copenhagen." But the audience is treated to several visions of events, and it's not at all easy to realize what is the Real Thing.

For that matter, is a passing lust to be taken as the Real Thing? Can any of these characters recognize true love when or if they chance to encounter it? Are they even capable of it themselves?

The cast is very good, but Jennifer Ehle—daughter of Rosemary Harris—is outstanding in her Broadway debut. Having the First Lady of the American Stage as a mother has proved a good inheritance. And her dad was once Governor of North Carolina, wasn't he? Something like that…

Tom Stoppard's works are always intellectually challenging and often rewarding. But why couldn't we have had a Broadway premiere of his "Invention of Love," as well as this revival?

His meditation on the frustrated loves of English poet/professor A. E. Housman had a very good production this past winter in San Francisco at the ACT. It could have been brought East.

After all, someone thought the ACT production of David Hirson's disastrous "Wrong Mountain" absolutely had to be seen on Broadway this season. Critics and public thought otherwise.

Noël Coward's "Suite in Two Keys" [**]

| |

| COWARD'S BITTER "SUITE"——Judith Ivey, Haley Mills, and Paxton Whitehead talk it over. Photo: ©—Joan Marcus/2000. | |

As originally produced in London, in 1966, it was "Suite in Three Keys, using the same hotel-suite for three rather different one-acts. Neil Simon has done this fairly well, with "Plaza Suite" and "California Suite."

Unfortunately, Simon has never risen to the level of Coward's wittiest comedies—which should have been revived instead of this and "Waiting in the Wings." But then neither Simon nor Coward has managed more serious drama very well.

The recent revival omitted the third London one-act: "Come Into the Garden, Maude." Just as well. Note that each of the three plays is named for an old popular song.

Paxton Whitehead played a somewhat restrained Paxton Whitehead as both tenants in the Lortel's Lausanne hotel-suite. Judith Ivey was satisfactory, but not memorable, in two roles.

Hayley Mills, bravely making her New York stage-debut in her mid-fifties, was also restrained, even a bit colorless, as two quite different wives. That seems required in the conception and writing of the roles, however. But it was sad that she had to return to London so soon after opening.

Critics were unkind to the plays and production. And there was no apparent surge of eager ticket-buyers, so the show closed abruptly. John Tillinger brought his usual skills to the direction—but they were less serviceable this time out.

At least we have been spared, thus far, from Coward's 1956 "Nude with a Violin." Bring back "Hay Fever," Blithe Spirit," and " Private Lives." Those brittle upper-crust British farces are Coward at his best—demonstrating his "talent to amuse."

Aphra Behn's "The Lucky Chance" [****]

Generally, I now avoid college theatricals—no longer feeling obligated to attend them in the line of duty as a professor of theatre. But I always make an exception when Elizabeth Swain is staging a show.And not just because she earned her doctorate from our CUNY Grad Center PhD Program in Theatre. She is a seasoned actress, with London, Broadway, and TV credits.

But she is also a gifted teacher of acting, as well as an insightful director. Her productions when she was head of the Theatre Program at Barnard College were a revelation: "Our Country's Good" and "The Rover," among others.

"The Rover" is a randy, ribald Restoration comedy, all the more surprising because it was written by a woman, the redoubtable Aphra Behn. She was not only the first woman to make her living from writing, but, aside from John Dryden, she's regarded as the most prolific writer of her time.

For some male contemporaries, her ability to write and think like a man was almost shocking, indecent even, in a woman. What most did not recognize was her ability to insinuate a woman's thoughts, feelings, and wrongs into her dramas.

Only now—with the rise of Women's Studies and fresh new systems of analysis—has her work been rescued from that White European Male-imposed limbo reserved for women artists and writers of past ages.

Mrs. Behn's "Rover," "Oroonoko," and "Lucky Chance" have all had major British productions. "Lucky Chance" even had an intimate and charming production Off-off Broadway some seasons ago.

Liz Swain's production, at Marymount Manhattan Theatre, lacked the cutesy unit-set of that previous presentation. In fact, this was not a loss, but a benefit.

Audience-attention could thus be concentrated on the actual performances of very able student-actors in handsome period costumes and splendid wigs, by Paul Hartley. They played like professionals against dark neutral drapes, with a few necessary pieces of furniture, a great four-poster bed, and some small set and hand-props.

You cannot do a Restoration comedy without fans. Against all expectation, Swain's talented Marymount College cast understood the Language of Fans and played them with skill and subtlety.

And the young men, as well, played their costumes, handkerchiefs, and snuff-boxes—like true Restoration gents and fops. Nor were the young women unconvincing as innocent virgins and worldly-wise ladies.

What was most interesting about the performances was the maturity manifested and the almost professional assurance, not only in manners and movement, but also in deft visual, verbal, and emotional clues to inner attitudes, thoughts, and schemes.

Dr. Swain is an admirable teacher of the basic elements of acting, but she is also remarkable in her work with plays of other times and cultures. Obviously, she has been able to help her student actors profit greatly from this.

Nor has she neglected the undercurrent of Behn's cleverly disguised concern with the needs and interests of women—high-born or lowly, often ill-treated and deceived—in Restoration England.

What would have routinely been a Happy Ending, then and now, with a man staging "The Lucky Chance," ends—in Swain's understanding of Behn's play-text—as a sad and bitter disappointment of a woman who expected so much more of the man she loved.

It is high time Swain was invited to stage another of Aphra Behn's unjustly neglected dramas for a major Manhattan ensemble.

There were too many good performers in this Marymount mounting to list them all, but some of the leads look like strong candidates for advanced work at the Juilliard School Drama Division.

Why shouldn't Marymount produce some of its own "Stars of Tomorrow"?

Anton Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya" [***]

Friends have raved—and raved and raved—about this current Roundabout "Vanya" revival at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre. My guess is that Atkinson himself would have had some reservations about Michael Mayer's casting and staging.Not to mention the clumsy, over-complicated, even ugly settings of the usually brilliant Tony Walton.

If the entire play had been conceived as some kind of vulgar peasant cartoon, it could have made visual sense to have a fine library of beautifully-bound books languishing on shabby shelves in what seems to be a log-cabin—with no mud to seal the cracks between the logs.

Even the costumes are a bit off-key. Roger Rees, as the mature Astrov—the hard-working country-doctor, who rides on muddy roads and plants seedlings in stripped land—is dressed in an impeccably tailored new suit, set off by shiny new boots.

Completely free of any traces of mud or dust, which could well be expected in such a place and time. What's more, he opens the play, lounging in a chair right in front of the first row of audience, his long legs spread apart, offering ample opportunity to study his boots and other apparel. This is a very exposed position.

Despite the raves of colleagues, for me, Rees really does not fill Dr. Astrov's boots.

I wouldn't go so far as to say—as some cynics have—that Sir Derek Jacobi, as the titular Vanya, is actually playing "I Claudius" all over again. Like Rees, he seems to have a clothes-sense that one seldom sees in "Vanya" revivals. Even though he's running a large, marginal, rural Russian farming-estate, he looks better dressed than most gentleman-farmers.

Laura Linney is lovely to look at as Yelena, the mis-married young woman who drives both Astrov and Vanya to distraction.

Amy Ryan is appropriately moping and ugly-ducklingish as the badly neglected and psychologically abused Sonya. Unfortunately, as Chekhov ordains in the play, she never has the chance to become a beautiful swan, even for a moment.

Brian Murray offers his usual bit of British Bluster as Sonya's self-important but superficial father, the unwillingly retired professor.

Rita Gam and Anne Pitoniak are also in the cast, playing aged Russian women—the former an addled aristocrat, the latter an addled old nanny.

Luigi Pirandello's "Naked" [***]

Down on East 13th Street, at the Classic Stage Company, someone had the unfortunate idea of reviving Pirandello's "Naked." Even in Nicholas Wright's new translation—or possibly because of it—actors are left dreadfully exposed. Naked, even.Her acting talents known previously from her films, Mira Sorvino courageously decided to show what she could do live. The role of the unfortunately wronged woman, Ersilia Drei, may also have been an unfortunate choice.

Sorvino seemed strangely muted, even in her experiencing the character's adversities and humiliations. This role seems to have been designed for Pirandello's muse and platonic mistress, Marta Abba, who had her own acting-ensemble.

Marta would have given it some real passion. I met Abba only when she was in advanced age, but she was still full of fire.

Daniel Benzali was outrageously audible and obstreperously visible as Pirandello's stand-in, the putative novelist, Ludovico Nota. Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Wright's translation was first played in London at the Almeida Theatre. More Brit Imports?

Zona Gale's "Miss Lulu Bett" [***]

At the Mint Theatre, Artistic Director Jonathan Bank has earned a well-deserved reputation for finding old but unjustly neglected dramas and restoring them to life. This season, his revival of Harley Granville-Barker's "The Voysey Inheritance" was widely admired.And I was very pleased with his fairly recent staging of the edition I'd long ago made of the Edith Wharton-Clyde Fitch dramatization of Wharton's "The House of Mirth."

So it seemed an interesting idea to bring one of the earliest Pulitzer Prize-winning American plays back to life as well. Especially as it was written by Zona Gale, the first woman to win the Pulitzer for drama.

Gale was an admired Midwestern "Local Color" author, having begun as a journalist. Her novel—about the unmarried sister who slaves away, unpaid and unthanked, for her more fortunate sister and her overbearing husband—was a national best-seller in 1920. Then she adapted for the Broadway stage, where it was also a critical success.

I had read Gale's play fifty years ago—when I was writing my doctoral dissertation at Stanford University. My topic was "Dramatizations of Popular American Novels: 1900-1917."

So Zona Gale's play lay outside my analytic boundaries. But it was similar in tone to many of the popular plays of a more innocent time—about just plain folks in American small-towns.

But, instead of extolling the ordinary virtues of hard-work, of suffering without complaint, and remaining hopeful in the face of adversity, Gale gave her downtrodden heroine the courage to break free.

The worm finally turned. But, even in a time of utterly simplistic local-color plays like "Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch" and "Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm," Zona Gale had some extra twists to her plot.

Lulu—ably interpreted by Angela Reed—on impulse accepts an almost joking proposal of marriage from her brother-in-law's own brother. She is a radiant bride. And the honeymoon trip opens up new and wonderful vistas to her.

Unfortunately—long before Arthur Miller had the idea—hubby proves to be already married to someone who is still very much alive.

Crestfallen, Lulu returns home, to the family who has missed all her free labor so badly. She has to prove to her own satisfaction that her short-time spouse really did love her when he proposed.

Her tyrannical brother-in-law tries to prevent this, as well as to keep the real reason for Miss Lulu Bett's untimely return a secret—to protect his own reputation in the community.

As Gale originally conceived Lulu's story, this turn of events gives her the courage to make a definitive break with the family and go off to make a new life for herself.

Decades before this—when Henrik Ibsen had Nora slam the door on her doll-house of a home in narrow 19th century Norway—Ibsen had to soften the ending for the play's first performances in Germany. As did Zona Gale, at her producer's behest, for Broadway.

The Mint ensemble, directed by James B. Nicola, performed the original version. But—after years and years of movies and TV series about small-time small-town Americans—these characters seem stereotypes, the situations contrived & schematic, and the dialogue virtually predictable.

We've come too far, seen too much, for such period plays to work effectively now.

Philip Barry's "Hotel Universe" [***]

J. B. Priestley wasn't the only popular playwright between the wars who was interested in the mysterious and the paranormal.Despite his reputation as a brilliant creator of Social Comedy—"Paris Bound" and "The Philadelphia Story"—Philip Barry was also fascinated by what might have been and what still could be. The Blue Light Theatre ensemble is to be congratulated on a stylish, if minimalist, revival of Barry's haunting "Hotel Universe."

The blondely beautiful Ann Field, on psychic impulse, has invited some long unseen Lost Generation chums to a lovely but strangely haunting villa on the French Riviera. Here, in isolation, she cares for her mysterious old father.

One of the bored party—all of whom are eager to escape and move on—hears a rumor that strange things have happened to people in this house, on this terrace. And so they soon begin to do, with alarming regressions to childhood and adolescence.

Some truths are brutally confronted. And some of these former gilded youths of the Jazz-Age are in effect liberated, reborn.

This may be a metaphoric Ship of Fools, but, unlike Sutton Vane's "Outward Bound," it is not an ocean-liner whose passengers are all dead.

As Ann, Arija Bareikis was quite as radiant as Gwyneth Paltrow. Richard Easton was magisterial as her aged father, a kind of Father-Confessor and Master of the Revels—which end with his ordained death.

Given the short run and small budget, this production was set and costumed simply but effectively, evoking the Age of Art Deco, the North Shore Long Island Rich, and rootless American Expatriates in France.

It was a refreshing change to experience a drama about wealthy, well-educated, well-mannered young people with problems of the heart and careers. Rather than one of those tell-it-like-it-is plays dealing with violent, illiterate ghetto youths with drug, venereal, and prison problems.

Barry belonged to another age. The Dead End Kids of his time were the boys next door, compared to today's rapping, menacing, desperate slum-posses.

Karen Sunde's "Balloon" [***]

Shown briefly in revival by Chain Lightning Theatre group at the Connolly Theatre, "Balloon" is Karen Sunde's imaginative attempt to fill in some blank pages in the "Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin."Franklin's once beloved—but later despised—bastard son, William, became Colonial Governor of New Jersey, under His Majesty King George III. This was initially galling to Franklin, if most gratifying to the insecure William.

He must always have been in an awkward position with his natural father. When Franklin performed his famous Kite Experiment, he had William hold the wet string, down which the lightning would course to the key. If anyone was to be struck dead, it wouldn't be Ben Franklin!

[A new children's drama dealing with this time, "Ben Franklin's Apprentice," has been handsomely & professional mounted by Stage One in Louisville, KY. In this show, the apprentice saves both Billy and Ben from electrocution when Franklin is making experiments leading to the invention of the lightning-rod.]

When the storm-clouds of the American Revolution began to form, Franklin urged his son to resign his Royal appointment and join the small band of rebels. Which he refused to do.

So William was imprisoned and ceased to be regarded as a son by Franklin. Even when his wife was dying in New York, he was not allowed to come to her.

Sunde's play alludes to another airborne invention, the hot-air balloon, in which Franklin himself made an ascent over Paris. This is celebrated in the Broadway musical, "Ben Franklin in Paris."

But her "Balloon" is not a lot of hot air. It's a fantasy which imagines Franklin's last evening in France, before he must return to the newly free American states. His beloved hostess, Mme. Helvetius, and her household of poets and politicians try to recreate the actual story of the relations between Ben and Billy, hoping to get Franklin to disclose something about this thoroughly closed account-book.

It is 1784, a year after Cornwallis' surrender at Yorktown. The Treaty of Paris has been signed. A new era of freedom is beginning across the Atlantic.

In five years, France will have its own Revolution, but much more violent and bloody than its American model. Aristocrats like Mme. Helvetius, their palatial homes, and their way of life will be savagely swept away. All in the name of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.

Franklin was wise to leave when he did. But Sunde's play offers only rumblings of the dreadful storm that was to sweep over France, especially in the forebodings of the dismissed minister, Turgot.

Gozzi/Taymor's "The Green Bird" [*****]

Julie Taymor's innovative production of "The Green Bird" is one of the most beautiful, original, surprising, and lavish shows on Broadway since—well, you guessed it!—her vision of "The Lion King."Though the new show at the Cort Theatre is being treated as a New York premiere, it was in fact shown two seasons ago on 42nd Street at the New Victory Theatre in a very limited engagement.

Critics are having difficulty in deciding whether this is a play or a musical. Or something entirely new and special. It is all of these.

Actually, it's an 18th century attempt—by Count Carlo Gozzi—to keep alive the spirit and the traditions of the old Italian impromptu traveling-theatre ensembles: the Commedia dell'Arte.

The talented Commedia performers were customarily dancers, acrobats, musicians, singers, and actors. To a bare plot-outline, pinned up backstage, they'd use all their skills and set-scenes to spin out their fairytale stories of thwarted love finally rewarded.

In addition to "The Green Bird," Gozzi also gave us the plays which became the operas "Turandot," "King Stag," and "The Love of Three Oranges." So Taymor's enchanting use of music, song, and dance are entirely in order. Her longtime collaborator, Elliot Goldenthal, has provided a score that is a constant delight.

The plot of the vanished royal twins—supposedly murdered by order of weak King Tartaglia's vicious Queen-Mother—has its roots in folk-tales, Greek comedy, and even Shakespeare.

The show's wonderfully realized Commedia stereotypes retain their traditional names: Brighella, Pantalone, Smeraldina, Truffaldino, and Pierrot.

Unfortunately, Gozzi was also trying to mock the Age of the Enlightenment's fascination with philosophic systems as guides for living. As a result, the long-lost Prince and Princess have to baffle modern audiences, young and old, with some arcane philosophical considerations which have no obvious contemporary resonances.

Voltaire did this much better in "Candide," which has a musical of its own. Maybe it's time for Taymor to try her ingenious hand with that show? Hal Prince has already had his innings with it.

There are so many astonishing scenic, lighting, and prop effects in "The Green Bird" that they alone are worth a trip to the Cort. How about an immense stone Talking-Head on rollers—with a smashed nose it wants mended?

Or singing apples that bounce up and down along red ropes like a musical staff—so the audience can sing along? Or a lovely nude female statue which comes to life? Not to overlook the fabulous Green Bird itself, perched atop a pyramid of shuddering skulls!

The large cast is entirely wonderful—and too numerous to list. But what doesn't quite work—at least when I saw the show early on Broadway—is the frenetic first-act Commedia clowning of the traditional characters.

This shtik has survived over the centuries, but the audience didn't seem to know what to make of it in this unfamiliar context.

Those who've read the rave reviews may come better prepared. Nothing is more painful than actors knocking themselves out when the audience clearly is not getting it.

The production concept is Taymor's, as are the direction and the mask and puppet designs. But Christine Jones [sets], Constance Hoffman [costumes], Donald Holder [lighting], and Jon Weston [sound] also deserve full credit for their contributions to this remarkable spectacle

If anything, it's too good for Broadway.

Musicals Old & New—

Meredith Willson's "The Music Man" [*****]

| |

| MAKING MUSIC WITHOUT INSTRUMENTS——Harold Hill shows how it's done in "The Music Man." Photo: ©—Joan Marcus/2000. | |

At one recent performance of "The Music Man," at the Neil Simon Theatre, a family with noisy small kids did manage to incur the wrath of critic John Simon. As variously reported in the "News" and the "Post," he informed the parents that the production was not a musical for children. Nor should the family be clapping and singing along.

This was early in the show, apparently. At the glorious finale, however, it's difficult not to want to clap in tempo and stand and cheer.

The stage gradually fills with the entire cast, marching and counter-marching in spiffy patriotic uniforms. Everyone, including the tiniest of tots, is playing a shiny new brass instrument or a percussion.

It seems indeed like Seventy-Six Trombones, as in the hit-song of this 1957 Broadway musical classic. There are a lot of trombones, but not quite 76.

This curtain-call finale is one of the most rousing on the Great White Way since that fabled anniversary salute to "Chorus Line."

It's almost half-a-century since "The Music Man" became part of American Theatre folklore, thanks to the wonderful songs, score, and book of Meredith Willson and the inspired Harold Hill of the late Robert Preston.

In the many revivals this show has had over the years, Preston has always been the act no one could really top. But Craig Bierko, the new and radiantly smiling Harold Hill, makes the role truly his own.

His smile could light up miles of subway tunnels. And his palpable charm could lure birdies from the trees and greenbacks from misers' pockets. His ability to sell band-instruments to small-minded small-town parents of goofy kids who cannot read music is totally believable.

So is his gradual transformation from hit-and-run scammer to solid citizen, thanks to falling in love with Marian, the lovely local librarian, in the equally radiant person of Rebecca Luker.

The show's dynamic opening of the interlocking patter-song of salesmen's complaints, linked to the repetitive clicking of train-wheels on rail joints, is a smash-hit, as it was years ago.

If you don't know the show, you may well worry that Willson and the cast have shot their energy-bolt at the outset—with nowhere to do but down. Not so. A profusion of well-remembered hit songs follows in rapid succession.

The vintage train-coach scene is set right up front, "in One." When it slides into the wings and rises into the flies, it's rapidly replaced by a colorful three-dimensional flown evocation of a charming Victorian town square, someplace in Middle America. It's set some time before we all lost our innocence.

There should be some major design awards for the sets of Thomas Lynch, the colorful and often comical costumes of William Ivey Long, and the ingeniously supportive lighting of Peter Kaczorowski.

Choreography, musical number-staging, and general direction are the inspired work of award-winning Susan Stroman. She's also responsible for the dance-theatre musical, "Contact," at Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theatre. If Stroman doesn't win a handful of awards this season, the voting critics must be blind and deaf.

This is a sweetly sentimental show, a musical ramble down Nostalgia Lane. And it is certainly joyously Wholesome!

Don't let that keep you away…

Webber/Rice's "Jesus Christ Superstar" [***]

| |

| RELIGIOUS RALLY——Cheering The Messiah in "Jesus Christ Superstar." Photo: ©—Ivan Kincel/2000. | |

When "Superstar" originally premiered on Broadway, however, it wasn't the banality and predictability of the songs that worried conservative taste-makers. The concept of the entire show seemed blasphemous in the extreme to Concerned Christians.

Even the title of Mary's impassioned ballad, "I Don't Know How To Love Him," inflamed some censorious clerics—who had neither seen the show nor heard the song performed.

Some viewers still make the mistake of thinking the Mary in question is Jesus' Virgin Mother. No, this is Mary Magdalene. She who caught Christ's Living Blood in a sacred chalice as He hung on the Cross of Calvary.

There are certainly enough medieval images of this hallowed act: woodcuts, paintings, enamels, sculptures.

In medieval times, there was a great Cult of the Magdalene. Great pilgrimage churches were built in her honor—Gothic shrines which today seem to have shifted their allegiance to the BVM.

There was even a mysterious tradition that Jesus had married the repentant Magdalene, by whom they had children. Some still believe that this Holy Blood lives on in the Royal Blood of some European princes.

So Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber were certainly on to something. That they didn't seem to do much with it could be because they never got round to writing the libretto they'd envisioned for this show.

I know this only because I once interviewed Lloyd Webber for "Opera News." The editor at that time was convinced that "Evita" and "Superstar" were in effect new—and certainly popular—operas.

He reasoned, not implausibly, that they should be considered modern operas because their stories were told entirely in music and song. No spoken dialogue!

The serious but affable young composer—later to become successively Sir and Lord—was flattered. But he assured me that there should have been librettos for both shows.

Rice and Webber knew the stories they wanted to tell, but they first had to arouse some investor/producer interest in their songs. The libretto would come later, when they were sure of a production.

Instead of a simple demo-record, they were able to record "Superstar" with a major orchestra. It became a major best-seller.

The rest is history. When producer Robert Stigwood decided he wanted to present "Superstar" on Broadway, the team was surprised to discover he didn't want them to write a libretto.

Stigwood correctly surmised that most of the audience would already know the Biblical story of Christ's Passion and Death. The songs—innovatively staged by the avant-garde genius of the hour, Tom O'Horgan—could carry the show.

The same thing happened with "Evita," whose liberally hated heroine drove producers away from the project. Rice and Webber had a great "demo" recording, selling like hotcakes, as they say.

No libretto was needed with the ingenious "Evita" staging of Harold Prince.

The new "Superstar" on Broadway, now on view at the Ford Center, could certainly have profited from the combined talents of Prince and O'Horgan. Even in their Golden Years, they could have devised something more interesting than the noisy gang-rumble director Gale Edwards has scattered over the stage.

Peter J. Davison's unit-set can charitably be described as a Post-Modernist evocation of an elemental Roman facade. But it's not amiss to call it, as one critic suggests, a concrete Overpass on some lonely section of the Interstate network.

Roger Kirk's black-on-black costumes make both the Romans and the Jewish Leaders look like villains. The often-attacked Oberammergau Passion Play—to be performed this summer for the first time in a decade—is pro-semitic in comparison.

Taking a cue from trendy opera-productions, in which CNN-TV crews capture climactic action on-camera for live-transmission, "Superstar" provides big-screen projections of Christ's Final Agonies.

What most impressed me about this multi-media device was the discovery that Jesus had some pretty good silver fillings in his divine teeth. You just do not think of good dentistry when you imagine Jesus riding into biblical Jerusalem on an ass. Palms yes, fillings no.

Glenn Carter seemed a fairly wimpy Jesus, nor was his mike turned up as high as those of his followers and tormentors. Especially those of his deadly enemies, who—as usual—were the most interesting figures on stage.

Although I saw only the understudy, Tony Vincent, as a punk-rock Judas, he was still easily the most dynamic, interesting character on stage.

Herod's effetely effective Art Deco Revue number was visually amusing, even though it came out of nowhere—through the Overpass. With no apparent relation to the rest of the show, for which one could be almost grateful.

Nonetheless, the show is so ferociously miked and so furiously played that it is sure to pack in hordes of the injudicious young for weeks and weeks. It is, however, unlikely to make many Converts for Christ.

John/Rice's "Aida" [****]

If you were able to guess the second rhyming-word in each pair of Tim Rice-rhymes for "Superstar" lyrics, you'll become a champion at "Aida." The banality of the images, the similes and metaphors, is beyond belief.And the rhymes are so obvious and simplistic. Verdi has nothing to fear from this show—which was once curiously called "Elaborate Lives." But that's still a song in this Technicolor pageant—which looks like a sequel to "The Lion King," set in another part of Africa.

Sir Elton John's music now sounds rather like tuneful wall-paper, suitable for any situation and surface. Could one consider it Generic John?

Will Disney this time reverse its customary process and make an animated film of "Aida," patterned on this production? It is sadly deficient in cute animals, however.

They could certainly make a much more impressive animation of "Lion King," if they started over with Julie Taymor's uniquely stunning vision.

Even with the stylized sets and costumes of the brilliant Bob Crowley and Natasha Katz's bold lighting, "Aida" still looks like a "Lion King" knock-off.

Visually, Aida" does have arresting effects and some dynamic stage-movement. But this is second-tier stuff, thanks to the talents of director Robert Falls and choreographer Wayne Cilento.

Despite critical reservations and outright attacks on the production, it is nonetheless clearly designed as a crowd-pleaser. I foresee that it will be once more a very long time until I am again able to enter the handsomely restored Palace Theatre to see the next new show there.

"Beauty and the Beast" kept it tied up for quite a while. Now that show has moved to the also newly and handsomely restored Lunt-Fontanne Theatre.

All that's now needed is for "Cats" to vacate the Winter Garden Theatre, so Disney can rebuild it to accommodate its technically complicated Berlin production of "The Hunchback of Notre Dame."

Linda Woolverton's book for this show—amended by director Falls and the once-promising, once young, Chinese-American playwright, David Henry Hwang—was actually "suggested by the opera."

This is admitted on the program's title-page. Hwang should have spent his time and talent on doctoring Disney's old Chinese fable of the Woman Warrior, "Mulan."

Verdi's original ending is a real downer for a family audience, however. What can you do about being sealed alive in a cramped chamber-tomb?

How can that be made upbeat?

Verdi didn't even try, but that has certainly not prevented his version of "Aida" from being one of the most popular operas of all time.

Disney takes no chances. You don't have to make marketing surveys to know there has to be some kind of Happy Ending.

So the show opens with a stereotypical scattering of Politically Correct museum-visitors strolling among the Egyptian artifacts. Center-stage is the stone-tomb, now empty.

Standing in one tall case is a figure of Princess Amneris, who comes to life as the real story gets underway. Other objects on display will later also play their various parts.

After the suffocating Love-Death of the duo of doomed lovers, it looks like it's all over. All-she-wrote, and all that gloomy stuff.

And, unfortunately, this death-agony occurs to the music of Elton John, not Verdi or Wagner, who were pretty facile with that kind of musical moment.

If you were worried and wondering if Michael Eisner and his minions believe in Life After Death, the Disney "Aida" should set your mind at rest. We not only live on in the spirit world, but we return to rejoin our own loves Millennia later.

The modern counterparts of Radames [Adam Pascal/"Rent"] and Aida [Heather Headley/"Lion King"] see each other across the crowded Egyptian Room of the prologue. And suddenly they know—as in some enchanted Rodgers & Hammerstein evening. Unfortunately scored by Elton John, instead of Richard Rodgers.

Headley is both a splendid singer and actress. Although some infatuated teen-age girls would disagree, the blandly blonde Adam Pascal doesn't seem worth dying for.

But he does take off his Egyptian threads frequently to show the effects of his gym workouts on his pectorals. They haven't done much for his diaphragmatic breathing, however. But who needs strong breath-support when you are so thoroughly miked?

For those ardent students of African-American history and its roots on the "Dark Continent," Disney's "Aida" should finally disabuse them of the notion that all the Pharaohs were black. Cleopatra VII and her ancestors were certainly Greek Ptolemys.

Black Nubia may once have ruled Upper and Lower Egypt for a time, it's true. But the Egyptians were another racial group. In the Disney version, they seem to be blonde and fair, for some reason.

The joke on the street is that Disney did this show because they needed a black doll to merchandise in their hordes of gift-shoppes. Pocahontas isn't quite the same thing.

Just before the matinee I attended, I watched a dad happily shell out $50 for a T-shirt, a small rolled-up poster, a souvenir program, and the cast CD. Disney has learned what museums already know: gift-shop souvenir sales can be almost as rewarding as admissions.

Add the staggering prices for orchestra-seats for a family of four—not to mention mid-town parking and lunches at Burger King—and you could have made a small down-payment on a house in Amityville.

Disco "Dream"/Nightmare "Donkey Show" [**]

Way back when I was reporting on the cultural scene for the late, somewhat lamented "After Dark," I was invited to the trendy clubs and discos. I think I'm too old for that now.It's a long dark stroll from the subway to Club El Flamingo, just across from the Chelsea Piers. Club Kids take taxis or limos, don't they?

There was a red carpet, velvet ropes, and a heavy-set guy in a tux. He didn't look friendly, but he nonetheless waved me inside.

In the midst of the noisy turmoil on the main floor—which could have been a form of dancing or just rubbing bodies—a disco version of Shakespeare's "Midsummer Night's Dream" was in progress.

This was hardly as well-structured as "The Boppity of Errors." another current updating of Shakespeare, designed for drinking-age audiences. If you weren't already familiar with the Bard's play, some of the parodic evocations would have to register on their own bizarre—and occasionally colorful—merits.

It reminded me of that long ago balloon-tent Bryant Park production of "Orlando Furioso," with its cast of nubile nude and semi-naked Italians pushing great set-props—and clumps of perambulating audience—around the vast space.

The difference at El Flamingo is that the space is cramped—rather like a small hotel ballroom. Nor was there the sense of Occasion about the event. John Cage and John Lindsay were not in the audience.

One novelty was women playing Demetrius & Lysander. Another was a quartet of fairies with buff gym bodies—and one with a fabulous tattoo.

Frankly, I was expecting something slightly obscene visually, from the show's title.

Most productions of "Dream" make much of the hairy donkey-ears of the transformed rustic craftsman, Bottom. King Oberon's spellbound spouse is enamored of them.

But it was surely a great joke for Shakespeare's own untutored groundlings—standing in the pit of the Rose or the Globe—to understand instantly why the fairy-queen, Titania, should be so delighted with a donkey as a lover.

Not for the size of his ears!

Another missed opportunity for artistic avant-garde outrage in Manhattan's trendy Chelsea/Clinton districts. Or did I miss something in the crush on the dance-floor?

Two Times Too Much "Wild Party"

Why would anyone want to set Joseph Moncure March's dated and dreadful poem of that name to music? Why would two composers want to do it?Why would two leading New York institutional theatres want to stage these two disastrous and depressing shows at the same time?

Is there such a thing as a dramaturgical Death Wish?

Andrew Lippa's MTC "Wild Party" [***]

Julia Murney was Queenie to Brian d'Arcy James' Burrs at the Manhattan Theatre Club. He sweatily suggested the vulgar clown, with the lust for violence kept just below his joking surfaces.And Murney/Queenie was very good at goading him to be abusive—masochism, tinged with fear. Throwing a wild party for various low-life and show-biz friends, in this context, was only delaying real trouble. Or spreading the risk.

The time was 1929, and Martin Pakledinaz's costumes evoked the period without excessive flash. Designer David Gallo's interfacing and irregular blocks of performance platform were moved about to heighten the effect of various confrontations at this shabby party in the depths of Prohibition.

The spareness of the production focused attention on the players, all of them very involved. But this was production was a Party from Hell I would have liked to avoid.

Andrew Lippa bore the entire responsibility for the book, the lyrics, and the score.

LaChiusa/Wolfe's Public "Wild Party" [***]

| |

| TONI COLLETTE——As Queenie in "The Wild Party" at the Virginia Theatre. Photo: ©—Carol Rosegg/2000. | |

Wolfe—who's artistic director of the Public—has staged his party on a much grander scale than the one at MTC. Designer Robin Wagner has created a cavernous and badly deteriorating Beaux Arts ballroom: an architecturally suggestive shell whose shabby pretension says a lot about the variously ambitious and frustrated party-goers.

This is a show of star-turns. There are even vaudeville placards to indicate successive entertainments.

Mandy Patinkin, as Burrs, is more over-the-top than usual. He even menaces the audience.

Toni Collette, as a blowsy blonde bombshell—or a low-rent Carole Lombard—is a revelation. She's a good foil and goad to Burrs.

It's astonishing to realize she was the unfortunate fat girl in that Aussie film, "Muriel's Wedding." What's her diet? She looks a lot slimmer than Fergie or Monica.

Tonya Pinkins rivals her with silky power. Eartha Kitt—who could be the grandmother of some of these gypsy-kids—is still able to dominate the stage when she has her turn.

As with Lippa's "Party" songs, LaChiusa's are serviceable, but not memorable. Of course, if one were condemned to listen to CDs of both shows for ten days or so, some might insinuate themselves into the subconscious.

LaChiusa has had a bad season. He has had two Broadway premieres—few composer-lyricists can manage even one now—but both were critically faulted.

It will be interesting to see if any theatres outside New York will produce his "Wild Party" or his "Marie Christine," a bayou Medea.

Lyric Theatre Treats—

For those who reject invitations to go to the opera—insisting they won't understand it—the pill might be sweetened by referring to the magnificent entertainments in store as "Lyric Theatre."Some recent opera-stagings in Manhattan certainly deserve to be saluted as the best of Lyric or Music Theatre. The days of the Fat Lady singing on a bare stage—backed by shabby painted scenery—are long gone.

Two Triumphs at New York City Opera—

Without taking any laurels away from Maestro Julius Rudel or Beverly Sills, the current City Opera management team—headed by Artistic Director Paul Kellog and Music Director George Manahan—is doing wonders to establish this ensemble as a model of excellence in stunning and innovative opera-production.Rudel can be regarded as a kind of Founding Father, with Sills the brilliant protégée, who donned his producing mantle with grace. Both were stalwart artistic stewards of the City Opera,

But it's only fitting, as the NYCO and its audiences move into the 21st Century, that new horizons be explored. Thanks to earlier showings at the Glimmerglass Opera, it has been possible to bring to Lincoln Center some outstanding new productions of forgotten or neglected operas. And mountings of Old Favorites wonderfully reconsidered.

Mark Morris Revises Rameau's "Platée" [*****]

Rameau's Comédie lyrique, "Platée," is much more than a baroque opera, based on a fable about the Olympian Gods. It also offers splendid opportunities for the most inventive choreographies.Director-choreographer Mark Morris has seized those opportunities with joy and great good humor. Instead of imagining the action in 18th century settings, Morris opens his lively show in a bar, with a great Victorian framing, including a terrarium.

Here—dressed as cops, hustlers, bar-flies, sailors, drunks, floozies, and other bar-types—the gods plan a lively spoof which will teach the pretentious swamp-nymph Platée a lesson about the excesses of vanity.

As costumed by Isaac Mizrahi, she's like a great overgrown frog. As played and sung by the wonderful Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, she is hilariously oblivious to her real appearance, while posing and preening ridiculously.

When it's suggested to her that Jupiter is so smitten that he wants to marry her, she doesn't even think of Juno's possible revenge for this bigamy.

Mizrahi's delightful costumes for the many birds, animals, and insects which haunt Platée's swamp are wonders of invention. As are the guises and disguises of the gods.

This could be a great show for children—there are English supertitles overhead—for the swamp-life alone. A wonderful way to introduce kids to the delights of Lyric Theatre!

But there's a risk: Do you really want to expose your children to the Facts of Life at the opera-house?

For the first time on any stage, I saw two turtles in carnal congress. It's not easy with those bulky shells, but they did it. Morris devises many other incidental visual amusements, some suggestive, some downright thigh-slappers.

The City Opera's singing actors, or acting singers, are all admirable. They blend effortlessly with Morris's manic dancers.

There's no sense that the singers are a race apart, incapable of fluidly graceful movement, or unable to enter into the hilarity of the mock wedding.

Adrian Lobel's main set—after the monumental William Saroyanesqe bar vanishes—is a giant version of the swamp-world of the tiny terrarium. Exotic in the extreme, it also leaves a lot of floor-space for the dancers. But it does have a pond!

Brian McMaster, Intendant of the Edinburgh Festival, suggested "Platée" to Morris. Now he should be urged to study the score and libretto of Rameau's "Les Boréades" as well.

This opera-ballet was produced last summer at the Salzburg Festival in a gleaming silver Art Deco evocation of 18th century architecture, staged and designed by the innovative team of Ursel & Karl-Ernst Hermann.

Morris' dances might wreak havoc in such an elegantly contained setting, but they'd certainly be more inventive than what was offered in Salzburg. Too refined and sedate for the stunning visual envelope.

It's immediately apparent in these Rameau operas that a variety of gracious dance-forms are intended to be executed. Either as meditative commentaries on the restrained dramatic action of the operas, or as total diversions.

There are extended sections in which no singing occurs because choreographies were required. They are not mere orchestral interludes.

A modern revival which cuts all or most of this music—and the ballets which might have been—does no service to Rameau's genius or to restoring the works and their formal structures for contemporary audiences.

Seriously Opera-Seria "Clemenza di Tito" [*****]

I remember well a Salzburg Festival production of Mozart's "Idomeneo," mounted nearly four decades ago. It was something of a sensation.Its novelty was not the ingenuity of the staging. There was none to see; the singers just stood there in costume on some steps, with Greek columns at either side of the great stage of the Grosses Festspielhaus.

No, the novelty was that this neglected, virtually forgotten opera seria was being performed at all. Mozart Opera had for decades meant the Da Ponte Trio, "Abduction," and "Magic Flute."

Soon, even such minor works as "Thamos, König von Aegypten" were being staged. This is really a fairly formulaic drama, with music by Mozart. One Munich critic described this experience as a "Musik-Seminar."

The idea that the magisterial figures in "Idomeneo" might actually have individual characters and emotions took longer to win acceptance. As well as the idea that these qualities could be played by the actor-singers, through gesture, body-language, and musical interpretation.

Clues to character and emotions are certainly indicated and developed in the music. As they are in all of Mozart's operas.