TWO VIEWS OF "MACHINAL"

by

Paulanne Simmons

by Lucy Komisar

|

Machinal

- A Lurid Murder Becomes a Luminous Play

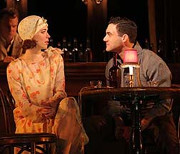

On January 12, 1928, Ruth Snyder (née Brown) was executed for the murder of her husband, Albert Snyder. Her execution followed a scandalous trial that revealed a lurid love affair resulting in a brutal murder. Even though a hidden camera captured her final moments in the electric chair, Snyder is largely forgotten today. But not completely unremembered. The trial did inspire playwright and journalist Sophie Treadwell to write "Machinal," an expressionist and feminist drama that opened on Broadway only eight months after Snyder's execution. The central figure in the play is a nameless Young Woman, and her only resemblance to the original is the fact that she too kills her husband and is executed. In the Roundabout Theatre's revival Rebecca Hall plays the Young Woman. And it is her stunning portrayal of an unhinged woman victimized by a society that did not understand or care about the female psyche that makes this play so poignant. But what makes it equally gripping is Lyndsey Turner's brilliant direction. The play is staged on Ed Devlin's revolving set on which the characters walk from one urban scene to another, the subway, the office, the cramped apartment. This gives the action a kind of menacing fatality that one feels can end in nothing but doom. These characters speak in a mechanical manner, devoid of emotion or understanding of the world they are in. They are the puppets of society. Thus the Young Woman walks through life doing what she is supposed

to. She marries her boss (Michael Crumpsy) because he will provide

for her mother (Suzanne Bertish). Marriage will also allow the Young

Woman to get away from The Mother's bitter nagging. "Machinal" has a large and very effective cast of supporting actors who all contribute to the feeling of a world disconnected from emotion and real relationships. Like the girls in the office and the guards in the prison, everyone is doing his or her job. And that is what makes this play so terrible and so tremendous. "Machinal" a powerful and inventive 1920s play about woman who murders husband 'Machinal." A woman is trapped in a system, caught in a machine (machinal,

from the French of or pertaining to machines), that turns her into

a victim any way she looks, whether she accepts her plight or fights

it. Sophie Treadwell's powerful and inventive play is a feminist

treatise about women forced into marriage and then self-destruction,

because they have no alternatives. It's a stunning drama, given

a rich, subtle, moving performance by British actor Rebecca Hall

in this Roundabout Theatre Company revival.

The play is painful but also invigorating, because it is so stylized,

naturalism replaced by an almost musical rhythm, staccato repetitions,

visual slow-motion and shadowy movements all designed by director

Lyndsey Turner. (Choreography is by Sam Pinkleton).

One of them, the man who pursues her, is J. (Michel Cumpsty), an

officious vice president of the George H. Jones Company. Cumpsty

is perfect in the role, exuding self-importance. At home with her

mother (the very good Suzanne Bertish), Helen sits at a plain wood

table covered with cheap stuff, maybe oil cloth, in a kitchen with

an old sink.

She has a baby and, lying in a white metal hospital bed, she declares,

"I'll not submit any more." Her thoughts are stream of

consciousness.

So comes rebellion. The office phone operator (an excellent Ashley

Bell) takes her to a speakeasy where she meets an attractive, laid-back

guy (Morgan Spector), called only "Lover."

With him, suddenly she is happy, feels hope. She is ethereal. The

play turns into film noir. Or maybe it's always been that. FIRST REPORTER: (writing) Under the heavy artillery fire

of the State's attorney's brilliant cross-question, the accused

woman's defense was badly riddled. Pale and trembling she – This is a play that anyone interested in American theater should see – especially given its origin in the 1920s — both for its powerful stheme and for its very inventive, original style. A milestone in feminist theater.

Visit Lucy Komisar’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com

|

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |