Two Views of "Golden

Boy"

|

Golden Boy Shines, by Paulanne Simmons. The Timeless Story of Golden Boy, by Lucy Komisar.

“Golden

Boy” Shines "Golden Boy"

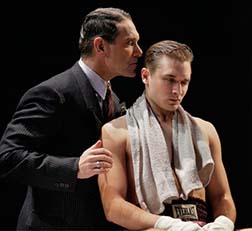

Seventy-five years ago, Clifford Odets, a high school dropout and founding member of the Group Theatre, wrote “Golden Boy,” a play about doomed love and unfulfilled dreams. The play came after his successes with “Waiting for Lefty” and “Awake and Sing!” and Odets’ move to Hollywood to work on films. It is believed that “Golden Boy” was inspired by the playwright’s own struggle between art and financial success. It’s certainly gratifying, and no big surprise, that the major struggles portrayed in “Golden Boy” have lost none of their interest or intensity so many years later. This is amply proven by Lincoln Center Theater’s current production, directed by Bartlett Sher. The play features an unusually large cast of 19, with Seth Numrich (last seen in LCT’s “War Horse”) in the lead role of Joe Bonaparte, the violinist turned prize fighter. Numrich’s sensitive portrayal of a man drowning in his own conflicting desires is matched by the equally fine acting of Danny Mastrogiorgio as Tom Moody, his promotor, and Yvonne Strahovski as Lorna Moon, Moody’s girlfriend and the woman Bonaparte comes to love. And Tony Shalhoub is heartbreaking as Bonaparte’s thoughtful and loving father, a role that could easily be over-sentimentalized. Although all these characters are close to stereotypes, Numrich, Mastrogiorgio and Strahovski manage to find the cracks in the facade that make their characters so totally real and human. These characters may not know it, but each is lost, something they find out tragically in the end.

Michael Yeargan’s set and Donald Holder’s lighting go a long way in helping establish the gritty world in which the play is set, whether we see the characters in Moody’s grimy office, in a city park, in the gym where Bonaparte is preparing for his fights or behind the scenes during the fights. And an excellent supporting cast completes the picture. Despite Odet’s ear for dialogue, many of the lines in “Golden Boy” do seem over-the-top, and many people will wonder why the criminals and ne’er do-wells in this play never use the four letter word that has become indispensable to modern playwrights. So it is important to take a trip back to the 1930s to fully appreciate the many textures and colors of this production. For those who know “Golden Boy” best from the 1939 film starring William Holden as Bonaparte and Barbara Stanwyck as Lorna Moon, this is the perfect opportunity to witness the vitality, immediacy and depth that live performances bring to a powerful story.

The Timeless

Story of “Golden Boy”

There’s a relationship here between values and the clouds of war gathering in Europe that establish a backdrop for violent attitudes at home. They are represented by the undercurrent pulling Joe from art to the dirty world of boxing represented by Eddie Fuseli (Anthony Crivello), a mafioso who muscles in to buy a piece of Joe’s contract. Crivello is tough, square faced, and carries a garish white coat that makes him a caricature of a TV Soprano. It is Eddie who nicknames Joe “the Golden Boy,” meaning he will bring in cash.

Odets’ women are stereotypes. Anna (Dagmara Dominczk), Joe’s sister, who is married to Siggie, a struggling aggressive frenetic cab driver, is crazy about him and lets herself be pushed around. Lorna Moon (Yvonne Strahovski), the secretary and lover of Tom Moody (Danny Mastrogiorgio), Joe’s fight manager, stays with him even though she doesn’t love him, because he loves her and needs her. Lorna is so damaged from past, she believes she has no right to her own happiness and is just grateful Tom rescued her. And Roxy (Ned Eisenberg), a fight promoter, is blatantly sexist. So maybe Odets drew those figures on purpose.

Joe says his nature isn’t fighting and talks with Lorna about souls. He declares, “In the street, there is rot.” But she tells him, settling for little, “All I want is peace and quiet, not love.” Still, later she will tell him, “We’ll find some city where poverty’s no shame.” Strahovski is strong as Lorna, the tough outside, soft inside broad from Newark who sports a Runyanesque Jersey accent.

Later we see Frank who has returned from the south, his head bandaged after he’s been beaten by company thugs. He declares, “I fight for what I believe in,” establishing the distinction between him and Joe.

Visit Lucy Komisar’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com/

|

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |