The Gates of Hell

|

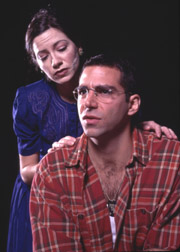

| Elijah Alexander as the pilot, Natasha Piletich as the psychiatrist. Photo by Jonathan Slaff |

"The

Gates of Hell"

Written by Robert Kornfeld

Directed by James DePaul

Theater for the New City

155 First Ave. (at E. 10th St.)

Th-Sat at 8 p.m., Sun at 3 p.m.

$10/tdf; Box Office (212) 254-1109

Opened January 31, plays through February 24

Reviewed by Paulanne Simmons February 14, 2002

In 1918, Dr. W. H. R. Rivers published an article in Lancet proposing a new "interventionist" method for treating trauma victims. This method required that the patient actively recall and face the traumatic event he or she was repressing so that healing could begin.

The method was highly controversial because at the time, the extraordinary fears, flashbacks and paranoia of traumatized individuals (primarily veterans) were generally considered symptoms of a syndrome known as "shell shock" or "battle fatigue" and treated with rest and rehabilitation.

"The Gates of Hell," by Robert Kornfield, now on stage at Theater for the New City, describes how a psychiatrist, Filora Nellmans (Natasha Piletich) bucks conventional wisdom to treat Mort Polhenmius (Elijah Alexander), an American army pilot who has become severely depressed four years after the end of World War II.

The play, directed by James DePaul, unwinds as a psychological mystery, as Nellmans attempts to unlock the past of her unwilling patient. The first act takes far too much time showing the audience that Polhenmius, an artist and Harvard graduate student who hails from New Orleans, is a suicidal intellectual, haunted, hallucinating and speaking (sometimes) in tongues; and Nellmans, a Nazi victim with a scar to prove it, is a noble-hearted earnest psychiatrist who will risk everything, even the wrath of her father, Deplod Nellmans (Bell Van Horn), a German émigré and traditional Freudian psychoanalyst.

But the play really takes off in the second act, when Nellmans hypnotizes Polhenmius and has him cause the appearance of the wonderful Aimée Nicole Lewis as Ana di Montemigniato (previously a wraith-like presence), who rescued and hid Polhenmius when he parachuted into the grounds of her villa outside Florence.

Lewis is childish, loving and playful. It's easy to see why Polhenmius falls in love with her. What happens to their love affair is the mystery Nellmans has to solve.

If the plot of The Gates of Hell is relatively straightforward, the play is nevertheless not for the intellectually timid. Kornfeld quotes or refers to Heidegger, Nietzsche, Sartre and Proust - and that's just the tip of the iceberg.

Although the principals involved are obviously highly intelligent, it's not clear what all this intellectual chatter actually does for the play. Nor is it evident why Kornfeld chose to include the subplot of Nellmans' conflict with her father. And at the risk of being called petty, why was this new "interventionist" method still in question over 25 years after it had been introduced?

If The Gates of Hell doesn't get too bogged down in over-philosophizing, it's mainly because of the brilliant performance of Alexander, who seems to have spent a good deal of time observing psychotics, in preparation for his role. If Piletich just didn't make Nellmans so painfully and unbelievably sincere, the play, especially the first act, might work a lot better.

DePaul has wisely kept the staging spare and abstract - suggesting the realm of the mind rather than the real world. He also keeps Alexander busy - running, falling, parachuting as he plays out his past

The Gates of Hell could use a lot of pruning and sharpening

of focus. But even in its present state, it's a totally satisfying emotional

and intellectual experience sensitive theatergoers won't want to miss. [Simmons]

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |