GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

Bregenz Diary 2001

By Glenn Loney, July 15, 2001

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

Outsiders & Impossible Dreams

Artistic Quality Instead of Quantity

State Visit from Vienna: President Thomas Klestil on Tolerance & Respect

"La Bohème" on Lake Constance

Steinbeck & Floyd's "Of Mice and Men"

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to

articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND"

button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal

correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor,

New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters

to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's

INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and

commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international

photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010.

Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

The Bregenz Festival 2001:

Outsiders & Impossible Dreams

|

|

WORLD'S

BIGGEST CAFE TABLE!--Giant Chairs & Parisian Bistro Tables are stages

for new lake-stage

Bregenz Festival production of "La Bohème." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001. |

And that's not just because the pile-driven foundations of the great open-air Lake-Stage opera productions go down deep into the waters of the Bodensee—or Lake Constance.

No, the depth is in the thinking, the planning, and the analysis of the festival program choices for their contemporary resonances. And their modern relevance to the lives of the thousands and thousands of spectators who flock to this westernmost Austrian city.

This is the essence of what Festival Director Dr. Alfred Wopmann has named the "Bregenz Dramaturgy." Both the War-Horses and the forgotten, neglected Drop-Outs of opera are selected for the Bregenz Treatment.

But Dr. Wopmann and his team are not simply searching for operatic works with terrific scores, dynamite plots, and larger-than-life protagonists.

Bregenz viewers should also be presented with operas of the greatest artistic merit, brought to vibrant life with the highest standards of performance, and with obvious entertainment-potential for audiences of all ages and from many walks of life.

Outsiders Dreaming Their Impossible Dreams—

But—beyond and above those goals—the operas selected should also be about important issues in Human Life, powerfully showing interesting people dealing with difficult situations, implacable enemies, hostile societies, daunting challenges, and even Dreaming Impossible Dreams.For instance, when George Gershwin's Porgy & Bess and Bohuslav Martinu's The Greek Passion were playing the same summer, the Central Theme of the Festival season was Outsiders.

For both groups of people central to these operas—disenfranchised American Southern Blacks and a displaced Greek community, routed by the Turks—were certainly Outsiders in the societies in which they were living—or trying to survive.

Actually, "Outsiders" would also have been a good thematic link this season for Giacomo Puccini's La Bohème and Carlisle Floyd's Of Mice and Men. Henri Murger's struggling young artists in their Parisian garret were also Outsiders. As indeed also were not only John Steinbeck's George and Lennie, but the other "drifter" ranch-hands as well.

If one thinks about this, many central characters of major operas are in fact Outsiders. That is often the source of their difficulties. And the mainspring of their dramas—which usually end in tragedy. Just make a Short List: Traviata, Trovatore, Aida, Alcina, etc., etc.

Dr. Wopmann's interesting idea of selecting a thematic core for festival programming is being adopted by other major music/theatre festivals as well. The Munich Opera Festival this past summer invoked Madonna—the soi-disant singer, not the Queen of Heaven.

The tenuous connection with Munich's festival opera offerings was Myth. Madonna has made her own Myth, it would seem. And the major new production at the Bavarian State Opera was Berlioz' The Trojans, which was inspired by a Certified Myth, as defined in Virgil's Aeneid. "Arms and the Man I sing…"

In Bregenz, there was no Myth-Making in the theme, but something rather related. Both operas examine the fates of men and women who are obsessed by what could be called—as in Man of La Mancha—"The Impossible Dream."

The Dream of Fame for Murger/Puccini's young artists. The dim-witted Dream of Hollywood Stardom for Curley's Wife, in Of Mice and Men. And the Dream of Home, George and Lennie's hopeless hope to own their own little farm "and live off the fat of the land."

Dr. Wopmann has spoken of the aspirations of the central characters in the Steinbeck/Floyd Music-Drama as instances of The American Dream. And he is right On Target with that comparison.

American literature, drama, and cinema are rich with tales of people destroyed by their desperate American Dreams of Fame, Success, Riches, or even just a Better Life. Arthur Miller's Willy Loman is perhaps emblematic of mid-century American Dreaming. Just as Tennessee Williams' Blanche Dubois is—in a rather different context.

But Bohème's clueless young artists aren't Americans, so the Bregenz Theme had to be broader. Dr. Wopmann has noted that the problems of would-be young artists in London today—or in Berlin, New York, or any other great capital—are similar. Perhaps even more complicated, with the growth of technology.

So their dreams—as with those of Lennie, George, and Curley's Wife—are, in a larger sense, Dreams in the Time of Capitalism. Dreaming of Making a Successful Career as a painter or a poet is perhaps as futile as Making It in Pictures or Making a Go of It on a Few Acres.

|

|

| SET 'EM UP, PIERRE!--Sequined chorus has champagne & a nosh around gargantuan table in Bregenz "LaBohème." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001 |

Artistic Quality Instead of Quantity—

For those opera-fans who "don't go to the theatre to think," all the Bregenz Festival productions—including dramas and dance-events—can be thoroughly enjoyed on a superficial level.The often unknown young singers will soon be seen and heard on major opera stages. The house pit-orchestra is none other than the famed Wiener Symphoniker. Chorus and dancers are from leading European ensembles, frequently from former Warsaw Pact nations.

But the directors and designers Dr. Wopmann invites to work on the opera-projects are not only among the very best and best-known. But they are also men and women who have regularly demonstrated their abilities to get to the core of operas and dramas. And they know how to make these essences visible, tangible, alive, important—even essential to Bregenz audiences.

This means intensive work with singer/actors to develop credible characters—inter-related with each other—not only through work on the actual texts and the music through which they are projected, but also through meaningful body-language: gesture, facial expression, and movement.

And—although some operas seem rooted in a specific time and place—Bregenz designers are always finding new ways to free the works from a Slavish Realism or a Romantic Mythos which often prevent audiences from making a real "connection" with them.

Some measure of the high regard in which the Bregenz Festival is held by opera/theatre professionals in Europe is the fact that its unforgettable production of Verdi's Maskenball—The Masked Ball/Un Ballo in Maschera—was awarded Bühnenbild des Jahres by the major opera-magazine: Opernwelt.

Of course, in translation, this honor was specifically for the physical production—rather than for the acting & singing—which were excellent.

But Bregenz's Festspielhaus staging of Bohuslav Martinu's The Greek Passion, of the same season, won the prestigious Laurence Oliver Award in London. No, London critics didn't fly off to Austria's Vorarlberg Province to see this shattering production. It was, in fact, a co-production with the Royal Opera, Covent Garden.

And Bregenz gave it its World Premiere!

This powerful Martinu opera was never produced in its original English version, even though commissioned for Covent Garden over half-a-century ago.

The Royal Opera got cold feet because it was confronted with the same super-pious religious objections which bedeviled the film-version of Kazantzakis' novel: A peasant portrays the Christ and re-enacts His Crucifixion, while his Blessed Mother is embodied by a local woman of questionable morals.

Martinu's Passion was such a success that next summer's indoor-opera will be his largely forgotten Julietta. And, on the lake-stage, Puccini's La Bohème will have its second and final season.

But these productions are only part of the festival-program. There are concerts, dramas, and more intimate operas, such as Astor Piazzolla's Maria de Buenos Aires, seen in 2000.

This was staged by Philippe Arlaud, who also astonished Bregenz audiences with his mounting of Italo Montemezzi's Love of Three Kings. This coming summer, he will direct and design Bayreuth's new production of Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser!

In previous seasons, Bregenz has invited Berlin's Deutsches Theater to share some its outstanding productions in the Theater am Kornmarkt. The DT was once Max Reinhardt's Berlin playhouse, in fact.

Now the theatre-component of the festival will be provided by Hamburg's excitingly avant-garde Thalia Theater. This ensemble has gained fame under the leadership of director Jürgen Flimm, who has staged Bayreuth's new RING.

Bregenz Festival productions can only be presented during the summer holidays of other major theatres and opera-houses. When their musicians, dancers, and performers have to begin their fall seasons, the great lake-stage—with its 7,000+ grandstand seats—usually has to sit idly in the autumnal sunlight.

Not so this fall—at least for some one- or two-nighters. Grease—which this summer seemed to be all over Europe—plays on the Bohème stage. My brochure of Coming Attractions from SHOW FACTORY also lists Magic of the Dance for this stage. In nearby Dornbirn, in the Messehalle, there's competition from Lords of the Dance. Like Grease, the Irish seem to be everywhere…

State Visit from Vienna: President Klestil on Tolerance & Respect!

|

|

YOU

CALL THAT STUFF ART?--Musetta surprised by sexual graffiti in artists'

garret in "La Bohème."

Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001. |

His remarks, on the occasion of the premiere of Martinu's The Greek Passion, focused directly on the problems of Outsiders, especially refugees and asylum-seekers. This is not merely a philosophical or academic issue in contemporary Austria.

In the dying days of East Germany's DDR, Austria welcomed thousands of East Germans fleeing that disastrous Social Experiment.

And now its borders are constantly being crossed, not only by East Europeans trying to escape the political and economic difficulties of their former homelands, but also by Middle Eastern and Asian refugees. Some from even from Afghanistan…

Many refugees are only passing through, hoping for sanctuary as far west as Britain. But Austria is a small nation now—no longer the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire. And it cannot support an endless flow of Outsiders. This has given rise to a Radical Rightist Reaction against these most unfortunate of Homeless People.

In his July address in Bregenz, President Klestil made specific reference to the Outsiders, the Others, in Steinbeck & Floyd's Of Mice and Men. He noted that Austrians should of course treat such people with Tolerance, even if their beliefs, customs, and dreams are not similar to those of native Austrians.

But even more important than Tolerance, Klestil insisted, is Respect. These people should be accorded respect as human-beings.

Of course, what he had to say to the Austrian festival audience could just as well have been said to Americans. Or to the United Nations General Assembly. Indeed, it should be said—and often.

But, even if Tolerance and Respect are invoked, there is still, as Klestil noted, the issue of the Rule of Law. Of the necessity in a free & democratic society to guarantee the rights of people who are not part of the Mainstream.

And that, he observed, includes protecting such people from unreasoning Prejudice: that no one should be pre-judged, defamed, or attacked without due process.

"Words are also Weapons, which often when they are uttered wound and discriminate," he reminded his listeners. And he urged both Politicians and the Press to take heed of these dangers.

President Klestil even suggested that Austria's longtime "Consensus-Democracy" was becoming a "Conflict-Democracy." In which not only Outsiders, but also Andersdenkenden—or Dissidents—are not treated with respect.

Referring to Of Mice and Men, Klestil said: Wenn die Welt so beschaffen ist, wie sie Georg und Lennie erleben, wenn dieses negativ Gegenbild einer menschlichen und gerechten Gesellshaft auch nur ansatzweise heute noch aktuell ist—sollten wir dann nicht unsere ganze Energie auf die kritische Selbstbestimmung konzentrieren?

He also deplored the tendency of the Media to exploit social and political conflicts. But even more shocking, he insisted, is the fact that almost every day, the Media bring us to some Theatre of War, Natural Catastrophe, or Human Tragedy.

Obviously, this is a general problem, not one confined to the Austrian press, radio, and TV.

But President Klestil noted that the reason he and his listeners were at the Bregenz Festival was Love, specifically their love of Music, which he said is probably in the blood of Austrians: "Above all, Opera is one of the most wonderful offerings of our Culture."

And: "Here the great cleansing working of Art begins: it restores to the Human Tragedies which it depicts their Individual Dimensions—which the Mass-Media have taken away from them."

Even more than that, however, such works awake in their audiences Empathy. Klestil continued: "Art has the possibility to make us better humans—people who are concerned about the misery of our fellow-men."

"And that certainly belongs to a festival. What we are also celebrating here is the possibility—in an unsettling time, which confronts us with completely new problems—to behave humanly."

Possibly President Klestil did not write this speech entirely by himself, but he certainly delivered it with strong conviction.

Americans could hardly expect their President to speak so eloquently, especially in linking the importance of the Performing Arts to solutions of Social Problems. But then George W. Bush doesn't have a doctorate, as does Dr. Klestil. And his speech-writers—of Republican Political Necessity—must be anti-Arts.

That is not to say that Austria does not also have a new and growing problem about Art, Education, and Culture. The long, dark shadow of Margaret Thatcher seems to have fallen over some Vienna politicians.

Or they may be echoing those American Conservatives who believe that even the Arts should pay for themselves. Governmental arts-subsidies are subsiding, to the consternation of opera and theatre intendants. As well as museum-directors…

Another political official from Vienna—come to help open the Bregenz Festival—was Franz Morak. He is a former actor, now Minister of Culture in an almost Thatcherite cost-cutting government.

His performance on the Festspielhaus podium may well have been more convincing than any of his roles on stage. There has to be a good reason why he left the professional theatre.

Borrowing from the late President John Fitzgerald Kennedy—who endeared himself to West Berliners with the enthusiastic: "Ich bin ein Berliner!" —Morak told his edgy audience: "Ich bin ein Vorarlberger!"

He didn't look or sound like one, however. And the previous summer, he had already cast a distinct chill over the Bregenz festivities by confirming the Austrian government's determination to make the arts pay their own way.

This past July, however, he saluted the Bregenz Festival—and effectively Dr. Wopmann and Festival President Günter Rhomberg, stewards of the fest—for the resourceful way in which they have secured corporate sponsorship and ardently marketed festival events to a large popular audience.

The Wave of the Cultural Future can be seen in Bregenz, where the Festival is now incorporated. It is not simply a form of State Theatre, depending largely on government subsidies. And of course on box-office income…

What will make this new form of arts-management and funding really viable, however, is an important change in tax-laws. Soon, it will be possible for Austrians to make tax-deductible contributions to Bregenz, Salzburg, and other festivals and arts organizations.

This will also soon be possible in Britain as well. So Minister Morak was more warmly received this summer than last. And he did not suffer the giggles President Kennedy encountered in Berlin.

To be a Vorarlberger—a native of that westernmost Austrian state or Land—has no hidden meaning. But Berliners are not only citizens of Berlin—they are also Jelly Doughnuts!

The festivities were enhanced by the Vienna Symphony playing selections from Puccini, a foretaste of his La Bohème on the lake-stage.

The major Festrede. however, was given by Dr. Michael Naumann, a noted author, editor, and general Kultur-Maven. In his "Celebrating Festivals—A Little Culture-History," he covered some 2,500 years of festival-making.

Those well-educated Austrians & Germans are nothing if not Thorough!

It makes one wonder: What would Public Dialogue in the United States be like if most of our politicians and media-moguls also had doctoral degrees?

La Bohème on Lake Constance!

|

|

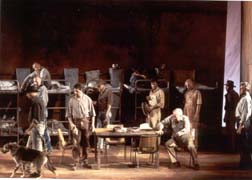

CALIFORNIA

DREAMING--Antony Dean Griffey & Gordon Hawkins as Lennie & George

in Carlisle Floyd's opera, "Of Mice and Men." Photo: ©Karl

Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001

|

Specially constructed for each of the two-season lake-operas, the Bregenz stages stand on piles driven into the muddy bottom of the Bodensee. These stages are always huge, not only because they face amphitheatre-seating for some 7,000 spectators.

But also because they have to support some truly spectacular scenic-constructions. No matter how intimate the scenes of an opera—or how subtle the intrigues of the plots or the emotions of the characters—astounding spectacle is the rule.

And, because the stage is set back from the front rows of the audience by the actual lake, there has to be some form of boat or ship at some point in the opera. Not to overlook the obligatory fireworks display.

But this season's lakeside opera, La Bohème—like Masked Ball before it—has only one really big scene. Its pathetic, sentimental tale is largely unfolded in a cramped artists' garret.

The same director/designer artistic-team who created the magnificent Bregenz Masked Ball—Richard Jones and Antony McDonald—faced a real challenge with Bohème.

What memorable form of monumental architecture and mammoth set-props could they devise for Puccini's opera of starving young artists and their unfortunate women?

Even though Mimi is dying of TB, another skeleton was out of the question…

So—instead of that gruesome tower of bones—all this autumn, winter, and spring, Bregenzers will be looking at Giant Café Chairs, rising out of the waters of Lake Constance.

The chair-backs can be seen kilometers distant, from German and Swiss trains—as Bregenz lies just between those national borders—and from the international highway, which passes right through the city. As in many past seasons, they are a very visible form of advertisement for the festival.

Many motorists—on their way to Munich, Lindau, Luzerne, or Zürich—stop to find out what those "things" are on the lake. And—if they can get tickets for the customarily sold-out performances—they stay-over and help fill local cash-registers.

Thus, the now-disputed State Subsidies from Vienna and even from the Land Vorarlberg for the Festival are very good investments. For the "trickle-down effect" of money spent on the productions and by tourists can be counted in the millions of Schillings. {Soon to be Euros!]

Jones & McDonald's Huge Chairs are not only sturdy and weather-proofed, but they also conceal important lighting-instruments and speakers.

They stand in the water—or are stacked—around three immense café tables. These represent the typical furnishings of a Parisian bistro such as the Café Momus—where Bohème's Big Scene is played.

But the opera actually begins in the cold, cramped garret of Rodolfo, Marcello, Colline, and Schaunard. How could the intimate hi-jinx of the "starving artists" be managed on such an immense stage-space?

How could Rodolfo and Mimi convincingly scrabble around the garret's supposedly darkened floor—her candle has blown out—searching for her key, when the immense stage has more ambient light than Times Square on a slow night?

Major opera-houses, of course, all have Bohème productions. And the problem of setting the garret in the large spaces of their often capacious stages is usually—and totally unconvincingly—solved by making the artists' loft bigger than Grand Central Station Concourse.

Jones & McDonald have taken another tack with this. Their café-table stage-round cannot be closed in. But to achieve intimacy, they have deployed large set-props which attempt to suggest different locales.

Chief among them are some immense Parisian Picture-Postcards lying on the stage.

One rises to form a wall-and-door to the garret. Another, lying in front of it, can rise from its raked position on pistons to become a level sub-stage. It can also be illuminated from inside, to highlight performers on it.

Another postcard farther upstage rises from horizontal to vertical to form an interior wall of Café Momus.

Instead of an immense Skeleton to dominate the skyline, Jones & McDonald have mounted a towering postcard-rack, leaning at an angle. This has three rotating faces.

To suggest a Christmas-tide atmosphere at the café, two vertical rows—with six giant postcards in slots on each side—show six horizontal sections which compose a sexy girl in Santa costume on the stage-right side and a complementary Christmas Tree at stage-left. The colored balls on the tree light up!

When this immense card-rack revolves, it reveals either a shabby vision of Parisian tenements—some windows of which also light up—or a selection of fuzzy, snowy views which add up to a street-scene in winter.

There's even an enormous phallic pink pen on stage for scribbling postcard greetings. At one point, Musetta's rich & foolish keeper finds himself astride this instrument as it rises in the air, leaving him stranded.

To extend the café-table image, center-stage there's an enormous triangular yellow ashtray—a familiar fixture in many Parisian bistros—with the logo of Ricard Anisette. Beside it lies an enormous champagne cork!

And where there are ashtrays, there will surely be Matches to light cigarettes. These are also enormous.

In order to fill the huge stage with some kind of activity while Mimi and her friends are relating to each other—the director/designers have deployed a Movement Group—not dancers as such—to move the matches around the stage.

Inside the circumference of the tabletop, the matches are variously laid out to spell PARIS, NOEL, MOMUS, HIVER, PRINTEMPS. As anyone who knows the opera will realize, these are not just cute visual diversions—though they of course do distract from the actual opera-scenes. They cue the audience to the nature or location of the scene currently being played…

Toward the close, the Movers stick some giant matches vertically in the stage. They soon catch fire, like guttering candles, later burning out.

The main table-stage is not the only one played. At the opening, high up on the smallest table, the audience sees a man and women disrobing for bed.

If you know the plot, you would be correct to suppose this is the demi-mondaine Musetta, preparing to entertain her despised keeper, Alcindoro.

This also would be a distraction from the main action downstage if it were clear & highlighted enough to make a visual point. Fortunately, it can be ignored, unless one is rapidly bored with what's happening in the foreground.

At the Dress Rehearsal—as I was seated far at the stage-left side of the bleachers—all these visual side-shows looked as important as the intimate scenes with the principals—which were far away.

At the premiere, however, I was front and center, and the real action came more forcefully into focus. But it was still like playing against a section of wall in Yankee Stadium.

Fortunately, some of the performers were not only able to hold their own in all this stage-prop spectacularity, but even to reach out empathetically to the audience. Especially outstanding was the Mimi of Alexia Voulgaridou.

She is not only beautiful—and a consummate young singing actress—but she has a power and purity of tone that will surely soon bring her to the Met and Covent Garden!

I should, however, note that I was tipped-off about her vocal and thespian excellences in character onstage by my old friend, Bavarian State Opera Kammersänger David Thaw. She studied acting for the opera with him at the Bavarian Theatre Academy, founded by the late Munich Intendant August Everding.

Rolando Villazon was also very appealing as Rodolfo. As the off-and-on lovers, Musetta and Marcello, Erla Kollaku and Marcin Bronikowski were fiery and admirable. Ulf Schirmer conducted this three-ring opera-circus.

The fundamental pathos of Puccini's opera—even with such a powerful score—was nonetheless somewhat undercut by all the visual sideshows.

The artists' landlord, for instance, seemed to be following events upstairs in the garret on his—closed-circuit?—TV, with his wife looking on in absorption. This was staged on the seat of the immense chair flanking the tabletop stage at stage-left.

On the surface of the middle tabletop stage, a ring of French chefs prepared flambée dishes during the Momus sequence. With lots of flames and flipped frying-pans.

When these cuisine-treats were ready, the immense group of Movers—all dressed in trendy Mod sequined outfits—streamed out onto the great circular balcony surrounding the mainstage.

They pulled red-leather stools out of the stage-drum itself so they could sit and enjoy their crêpes suzettes. Or whatever…

As for Musetta's Waltz-Song and her Big Moment trashing Alcindoro, the obviously unhappy duo—sparkling in sequins— were seated center-stage on a recumbent postcard. Like Madonna at a Major Concert, Musetta took the mike from its stand and proceeded to do her stuff like a trendy Rock Star.

Any why not? How can you win modern audiences—especially young people—to opera unless you make it look like another World Tour by Michael Jackson?

Of this Bohème, one could certainly say: Never a Dull Moment.

But never a Quiet Moment would be more like it. These diversions distracted from the core of the action and emotion.

Perhaps some of this extraneous and gratuitous Movement will be reduced or removed next summer? They would do that at Bayreuth, of course. But Bregenz is not Bayreuth…

The intimate scenes in Masked Ball did not suffer in this way. The stage was variously filled—or traversed—by dancers and extras whose costumes, patterns, and movements were in themselves impressive, dramatic, even beautiful, to behold. But which also enhanced or framed the core-actions.

It may have been intended only as a High-Spirited joke—possibly to enhance the pathos of Mimi's approaching death in the garret—but shortly before this, the four comrades went wild painting rowdy sexual graffiti on the postcard wall of their garret.

Earlier visible artistic efforts by Marcello, the painter of the quartet, indicated that his hopes of success as an artist were indeed in sync with the Festival Theme. He, like the other three, was obviously dreaming an Impossible Dream.

Paris is, of course, divided by the meandering River Seine. But Jones & McDonald didn't opt for a touristy bateau-mouche for the obligatory Bregenz Festival boat.

Instead—perhaps inspired by Parpignol's Christmas toys for the kiddies outside Café Momus—a giant folded-paper cocked-hat boat floated before the stage, piloted by what looked like the Easter Bunny!

As for the customary fireworks, this time they were replaced by explosions of red and green paper coils, such as those used to send off the Titanic on its Maiden Voyage.

One eagerly awaits Season 2002 in Bregenz. Will this production remain entirely unchanged? Or…

Almost a Folk-Opera

But Certainly a Heart-Breaker!

|

| GOING OFF TO SHOOT THE OLD DOG--Symbolic scene in ranch-hand's bunkhouse in "Of Mice and Men." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001. |

John Steinbeck & Carlisle Floyd's Of Mice and Men—

Composer Carlisle Floyd is probably best known in America for his opera, Susannah. But his powerful treatment of John Steinbeck's short novel, Of Mice and Men, in its own way is quite as distinguished an achievement.This the Bregenz Festival's Intendant, Alfred Wopmann, recognized immediately when he saw the recent New York City Opera production. Although the work had been premiered long ago at the Netherlands Opera, it had no further European career of note.

So introducing it to contemporary opera-audiences in Bregenz was almost like a European premiere. It was, in fact, the Austrian premiere.

And it proved popular with the general public—although it is, by definition, a "modern opera"—because its musical modes are thoroughly accessible and eminently apt for the situations, characters, and passions of the tale.

Without recourse to ardent avant-gardisms, dissonances, and serial tone-games which would have called attention to themselves, at the expense of this Depression Era tragedy of small lives and shattered dreams.

Somewhat like Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, Floyd's Of Mice and Men comes close to being an American Folk-Opera. Especially in the bunk-house with the ranch-hands, when the Ballad-Singer evokes a vision of the wide-open spaces and the romance of the Old West.

And because Nobel Prize-winner Steinbeck's novels have remained popular in Europe—if largely neglected in America—this simple, direct, honest work of great human pathos was doubly welcome.

This heart-wrenching tale of two homeless drifters, dreaming of a real home of their own—their own little farm, where they can, as Lennie says, "Live off the fat of the land"—is by no means trapped in the preservative amber of memory of a bygone time in America.

Steinbeck's novella, the play based upon it, and Floyd's opera-libretto remain vital and contemporary: Homeless people—seeking asylum, work, safety—continue to flood across the Austrian border from Eastern Europe.

If anything, the problems of the modern Georges and Lennies—from Poland, Romania, Macedonia, Albania, and even Afghanistan!—are even more potentially pathetic, even tragic, than those of Steinbeck's 1930s drifters.

The American West—especially California, the "Golden State"—had room for the newcomers, the Outsiders, with their perhaps impossible dreams. In fact, it still does. And still they come.

But Austria—and its thickly settled neighbors, Germany and Switzerland—never had any wide-open-spaces. And the constant stream of needy homeless can be threatening to settled and satisfied citizens—who have been trying to stabilize their lives and society since the horrors and displacements of World War II.

Thus, director Francesca Zambello has made the right choice in giving this production a generalized Californian character, but not one rooted in the 1930s. This powerful if elemental story is unfolding Now.

Not in Austria, not on a dairy-farm in Vorarlberg, but in America. In a modern America, not in a big city, but on the land. And it speaks both simply and subtly across the continents.

|

|

GET

UP! GET UP! I DIDN'T MEAN NO HARM!--Frantic Lennie tries to revive Curley's

Wife in "Of Mice and Men." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz

Festival/2001.

|

As Lennie Small, Antony Dean Griffey was almost heart-breaking as the seemingly Gentle Giant who loves soft things but who does not know his own strength. Steinbeck's ironic name emphasizes his big frame and powerful muscles. He is anything but small.

He not only sang his role beautifully, but he also played the great child that Lennie is with touching pathos. When his despairing friend and protector, George Milton, finally had to shoot him—to prevent the lynch-mob from doing far worse to him—people all around me were wiping away the tears.

Steinbeck visualized George as small and wiry, a highly-strung contrast to Lennie in almost every way. But they share a dream, the vision of their own little farm.

In the Bregenz production, the big, powerful Gordon Hawkins is a physical match for Lennie—and a strong vocal contrast. But the Steinbeckian irony of a small nervous man protecting a large placid child-man was transmuted into a parallel paradox. George is black—which makes him even more of an Outsider in rural situations—but he is always protective of his white ward.

Steinbeck & Floyd's Curley—whom some Austrian critics assumed was the ranch-owner—is, in fact, only a kind of foreman. And as he is small, he over-compensates by being aggressive and bullying—to puff up his own sense of importance.

Joseph Evans was effective in this role. Especially when Lennie crushed his hand after he had picked on him, and the other hired-men threatened to report what had really happened.

What was especially impressive about this production was the thoroughly believable quality of the acting. This could have been a Broadway staging of the play, instead of the opera. Zambello is obviously a wonder working with actor/singers.

Especially right for the Great White Way was Nancy Allen Lundy as Curley's sexy, sluttish wife. Bored to death on the ranch, with no trips to town to movies or dances, and no action or even attention from her new husband, she flaunts her very attractive sexuality in the bunk-house.

Poor simple Lennie, flattered by her attention, doesn't even know what a big man like him might do with such a pretty woman. All he wants to do is stroke her beautiful soft blonde hair…

But she gets scared and pulls away. As he did with his mouse and his puppy, he tries to make her be quiet. The minute she stops moving, he knows he's done something Very Bad.

Two Impossible Dreams have come to an abrupt end at once. Curley's Wife will never get an audition, a Screen Test, or become a Hollywood Starlet. And Lennie and George—now that they will have to be on the run again—will never have their little farm.

Of course, the Steinbeckian irony of both those dreams is that they could never have become realities anyway.

|

| GEORGE! I SEE IT! I SEE OUR LITTLE FARM!--Heart-broken George [Gordon Hawkins] prepares to kill his child-like buddy, Lennie [Anthony Dean Griffey], before the lynch-mob comes to get him. Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival/2001 |

Curley's Wife—even if she had any acting-talent—would have been used and abandoned by the man who promised to put her in "Pictures." If he did not also prove to be a White-Slaver, a pimp.

In the 1930s in California, it was almost impossible to maintain even a subsistence living on only a few acres of farmland. And, if there was no income from farm-produce, George and Lennie would soon have lost their land for unpaid taxes!

Others who made the action both believable and deeply affecting were Julian Patrick as the aged Candy—whose old smelly dog is shot, a foreshadowing of Lennie's death; Peter Coleman-Wright as the jerk-line mule-skinner Slim, and Douglas Nasrawi as Carlson.

Patrick Summers conducted—as he will in Houston—but in Bregenz he was working with the Vienna Symphony and the Moscow Chamber Choir.

The very impressive—but essentially elemental—settings were created by the ingenious London stage-designer, Richard Hudson. His strongly skewed scenic-environment for La Bête on Broadway has passed over into legend.

Shortly after that scenic triumph, I interviewed him in his London studio. And I have been following his career ever since. His sets for Of Mice and Men are so simple but powerful that they ought to be seen in New York—even if the City Opera already has its own production in storage.

Perhaps at BAM? After Houston, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC?

When I entered the auditorium during tech rehearsal, I saw two sets of rails jutting outward and upward toward the audience. With low open box-cars on the rails—and a high-tension tower in the distance.

This image astonished me, for I was certain I had already seen it someplace.

When I asked Hudson where he had used this before—or if it had been inspired by some other setting—he assured me that this was absolutely original. And then it dawned on me that I had dreamt this image only a few nights before I actually saw it on stage. Go figure…

I did point out to him that these were not American rail-cars, because each had two little shock-absorbers on each end, at either side of the iron panel. Hudson couldn't believe American freight-cars—at least in the past—did not also have those odd items.

As an amateur train-buff, when I first came to Europe, in 1956, those shock-absorbers were one of the first differences I noticed between American and Continental trains. Hudson was surprised, for he supposed period rail-cars were much alike.

The almost surreal cast- & wrought-iron rusted farm-machinery—in front of which Lennie accidentally kills Curley's Wife—I thought must also be some kind of archaic European engine, or Hudsonian Invention. I'd never seen anything like it on an American farm or ranch.

Hudson assured me, however, that it was modeled—but not copied in detail—from an image of just such an actual farm-machine. As we looked at this imposing set-prop backstage, I began to see that it could have very well been based on some form of corn-shucking machinery.

At close range, I was astonished to discover that both this "infernal machine" and the rail cars were in fact made of real iron, steel, and wood painted to look like metal.

Hudson and Bregenz's Technical Director, Gerd Alfons, introduced me to the man who made these impressive props, Romania's Eugen Postolache.

He has also created props for the innovative Viennese set-designer, Hans Schavernoch. Among those shows have been the spectacular musicals, Freudiana and Elizabeth.

Postolache maintains shops in Bucharest, where he employs over a score of skilled workmen to construct props and scenery. His work is in such demand now, that he also has an office in Vienna.

He has studied art & design in the United States, so his English is both idiomatic and excellent.

I used to write, edit, and publish The Art Deco News, so I was doubly charmed when Postolache told me he calls his company ARTDECO!

Anyone reading this who would like to find out more about his work can contact him email at: artdeco@penet.ro

The only scenic element in Hudson's vision of a Steinbeckian ranch in Salinas' Long Valley that jarred historically was the bunk-house.

With double-decker metal Army cots along the wall and folded-up bedding, it looked just like my barracks at Fort Ord in 1953—only a few miles away from Salinas, as it happens.

If this production had been intentionally set in the pre-war era—which it was not, of course—the bunk-beds would have been made of wood. Factory-made cots cost too much!

In fact, in Salinas—at the National Steinbeck Center—there is a museum mock-up of George and Lennie's bunks. They are made of wood, just like the ones the Loney Brothers and my Salinas cousins used to have for their ranch-hands!

Curiously, in Bregenz, Carlisle Floyd's Of Mice and Men was often referred to—both orally and in print—as one of America's most successful modern operas.

I certainly agree that—as a musical-version of Steinbeck's novel, and as an opera on its own terms—it is indeed a major artistic success, one of which Floyd can be justly proud.

But the truth sadly is that it is all-too-seldom produced or performed.

When the New York City Opera imported its bare-bones—but striking—Glimmerglass Opera production several seasons ago, it was indeed well received.

This was the production that Dr. Wopmann saw, the one which convinced him Floyd's opera must be seen in Europe. And he could well have left the New York State Theatre, believing that this staging was a big success. The reviews seemed to affirm that.

But new productions at the NYCO are customarily introduced for some three performances only. If they strike sparks with audiences—as well as critics—they will return to the repertory the following season.

Lack of sufficient audience-interest may have been the reason, but this powerful production did not appear again.

When I had the opportunity to talk with Floyd—we stayed in the same hotel—I noted this discrepancy between the fabled "success" and the failure of the City Opera to capitalize on it and maintain Of Mice and Men in the permanent repertory .

Floyd suggested I ask City Opera's Paul Kellog about this oversight.

Considering the opera's tremendous critical and audience reception in Bregenz, NYCO ought to take note and bring back their fine staging.

They have even more reason to do this as their production is elemental, and thus not especially expensive to revive.

Not to overlook the publicity potential of having possibly One-Upped the Houston Grand Opera, which has co-produced Of Mice and Men with Bregenz.

And the Bregenz production will almost surely also be shown at the Los Angeles Opera and the Washington DC Opera.

That is, if the reactions at the General-Probe of Placido Domingo—who is the operative power in both those American opera ensembles now—is any indication. He seemed both moved and impressed!

[Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2001. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| museums | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |