GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, December 23, 2000

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] "Jane Eyre"

[03] "Fermat's Last Tango"

[04] "Pete 'n' Keely"

[05] "A Child's Garden"

[06] "Christmas with the Crawfords"

[07] "The House of Seven Gables"

[08] "Old Money"

[09] "Tiny Alice"

[10] "The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant">

[11] "Princess Turandot"

[12] "Circus Oz" at the New Victory

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire.

For archival versions of Glenn Loney's past columns, please try our internal search engine or click here.

Holiday Greetings 2000-2001!

RING OUT THE OLD!

RING IN THE OLD AGAIN!

Musicals Old & New-Old—

The coming of the New Millennium was supposed to herald dramatic changes in the way we live and celebrate the Gift of Life. Inspired innovations and recharged human imaginations would give new vitality and relevance to our social, spiritual, and cultural lives. At least in the musical-theatre areas of the performance sub-division of the arts, not much has changed. Recent premieres on and Off Broadway break no barriers and offer little cause for jubilation.Pressed for time, I can do little more than briefly comment on the new productions below. Generally, not an outstanding offering.

"Seussical: The Musical" [***]

| |

| David Shiner as Dr. Seuss's Cat in the Hat. Photo: ©Joan Marcus, 2000. | |

I am of the generation before Dr. Seuss's fantasies became Required Reading. So I know about Cats in Hats and Green Eggs only by report. Thus, much that happens on stage seems somehow incomplete. As though you should have read the books and studied the drawings over and over, long before you came to see the musical.

To enjoy this new show to the fullest, you need to be a Dr. Seuss adept or fan. For me, it does not stand alone on its own merits. Most musicals are based on previously popular, audience-tested novels, plays, or films. But to succeed artistically—as well as with the mass-audience—they need their own inner integrity and appeal.

"Seussical" is too cute, too precious by half. The Whos are annoying enough in the new film, without being recycled on stage. The movie is not another "Wizard of Oz," and the musical certainly is not a contender against "The Wiz."

The stocky hero, Kevin Chamberlain, was sympathetic in "Dirty Blonde," but here he seems to be playing the same role, though pretending to be an elephant. He is right to ignore the love-pangs of the bird with the very long tail.

How odd that the mime-duo of David Shiner and Bill Irwin—seen together on Broadway in "Fool Moon"—are now both employed in non-mime roles in Seuss-derived entertainments!

The musical's book and songs are the work of Lynn Ahrens & Steven Flaherty, who also gave Broadway "Ragtime." The music is serviceable, but not memorable, just as in their previous effort.

Speaking of effort, it must be noted that the cast really knocks itself out to get the audience to pay attention and enjoy the show. It is obvious they want us to love them, not for themselves alone, but as comical characters with funny names. There is tremendous energy expended on stage. And they are all professionals. This is not performed as Children's Theatre, where the most appalling amateurism, condescension, and egotism prevails.

Nonetheless, there is also a sense of desperation. Especially in chorus-numbers, where some outrageously inventive William Ivey Long costumes seem to have been thrown in at the last minute to jazz up a lackluster number. Unfortunately, as they are on minor characters, they go for nothing. We don't have an opportunity to see them in a major way. They flash on, and then they are gone again.

Maybe there will be a Dr. Seuss Museum in which these costumes can be properly displayed?

"Jane Eyre" [***]

For those who prefer their Broadway musicals no longer than a popular film—say, 120 minutes or less—"Jane Eyre" is closer to 180 minutes playing-time. But it is still shorter than that great film classic, "Gone With the Wind." And it's certainly shorter than Wagner's "Parsifal."Blame it on TV-induced short attention-spans. Or the simple fact that we are uncultured Americans who lack the staying-power of Germanic Wagnerites who seem able to sit very still for hours, savoring the Music Dramas of the Master.

Oddly enough, however, it was not I, but my German guest who departed at the intermission. He is a Living Legend in the former East Germany, where he was, in turn, artistic director of the Leipzig Opera and then of the great Semper-Oper in Dresden. In fact, he had come to New York to lecture for the Wagner Society and show his 1964 black & white film version of Der fliegende Höllander.

What he disliked was the formulaic quality of the musicalisation of Charlotte Bronté's novel. Not to overlook its grim determination to document or narrate all important events in Jane's sad life from childhood onward. But least attractive of all for him was the score and songs, which he found as trivial and predictable as those in operetta.

I stayed to the end, actually enjoying the production most of the time. But immediately after, on the uptown 104, I overheard a very authoritative woman tell her friends that the music was: "terrible! Too operatic!"

For my guest, I guess, it was not nearly operatic enough. That a serious subject, if it's worthy of musical treatment, deserves a serious and powerful score and libretto.

These John Caird and Paul Gordon have not provided, though the show certainly has many serious—even depressing—moments. It also has some soaring, haunting songs—a few of them with operatic overtones which are quite attractive.

The major problem with "Jane Eyre" is not only that it is too long, but that it is too long for the wrong reason. Why Caird and Gordon felt obliged to replay Jane's complete chronology—hunks of it narrated by a black-clad chorus—instead of cutting to the chase, is a mystery.

The great Greeks, Sophocles especially, understood the increased dramatic impact of unfolding their plots from strong moments of conflict and confrontation, leading swiftly to climax and catharsis. It was not necessary to narrate, or to act out, the entire Trojan War as a prelude to Agamemnon's Homecoming and murder by his wife and her lover.

"Jane Eyre" would be a far more powerful and moving musical—without losing any of its unusual production-values—if it began at Thornfield Hall, possibly with Jane's first inkling that there's something strange upstairs. And that there's certainly something strange—even tragic—about her brusque and mysterious employer, Mr. Rochester.

To help define her own character—and the reasons she acts and reacts the way she does—there could be brief flash-backs to her past. Neither the actors nor the audience should have to wade through pages and pages of the novel before she comes to Thornfield. Her developing relationship with Mr. Rochester is the heart of the story, and it should also have been the core of this new musical.

Nonetheless, as the lady on MTA 104 said: "They all worked very hard!"

In fact, "Jane Eyre" has a very talented, versatile cast. James Barbour is not only a virile, handsome Rochester, but he has a fine singing voice which he uses to impressive effect interpreting his songs. Previous Broadway musical credits include The Beast in Disney's "B&B" and Billy Bigelow in "Carousel."

Marla Schaffel's Jane is more muted but ably, sensitively realized. She is a Plain Jane for most of the action, but she can be radiant in wedding-finery and later, in the fullness of her love for the maimed and blinded Rochester—after his mad wife has burned herself and Thornfield to ashes.

If the plotting and musical numbers of this new show seem retro, with the obligatory comic character—Mr. Rochester's relative and housekeeper, Mrs. Fairfax—its scenic-design is innovative, if unsettling. Its constantly moving, rotating, swooping gauzy curtain-panels create scenic illusions with projections.

Designer John Napier has devised an overhead center-stage revolve of lights and curtain-tracks which complements the revolving stage below.

But he has also designed a variety of floating windows which glide through the empty air, halting in space for a special scene and then disappearing again. This is not only disconcerting: it becomes a design-cliché: "Look where it comes again! "

Creators Caird and Gordon are so obviously wedded to their concept—which they have been auditioning for some time—that they surely now will not consider cutting the show by cutting to the chase. The pity of it is that they did not begin developing the musical that way.

Or they could have based their musical, not on the novel, but on a recent Alternative Theatre production from Britain, shown at BAM and the Edinburgh Festival. In this version, the mad, attic-imprisoned Mrs. Rochester becomes a clinging second-self to Jane, an alter-ego and a symbol of her repressed libido: of emotions also imprisoned in her own spiritual attic. The various episodes of the novel were drastically compressed and swiftly played by a small ensemble. Men even doubled as Mr. Rochester's horses and hounds! That book would have made a dynamic musical!

"Fermat's Last Tango" [**]

|

| LAST TANGO FOR FERMAT—Chris Thompson and Jonathan Rabb Photo: ©Carol Rosegg, 2000. |

As I left the intimate theatre, I said to Village Voice critic Michael Feingold, "It's 'Proof' set to music!"

Michael—who is the contemporary critic I most admire, now Jack Kroll has passed on—clued me in: "This was supposed to be called 'Proof,' but the play opened first, so they had to change the name."

Why anyone would want to write a play, let alone a musical, about a nerdy professor solving Fermat's Last Theorem—which was long thought insoluble—is to me a puzzle more baffling than squaring the circle.

But—throwing caution and their slide-rules to the winds—Joshua Rosenblum and Joanne Sydney Lessner have certainly pushed their talents to the limit to do just this.

Dressed in foppish French finery of his era, Fermat appears in Prof. Keane's attic study to taunt him. The prof's recent media celebrity for announcing his proof is flawed.

Euclid, Sir Isaac Newton, Pythagoras, and C. F. Gauss also materialize to provide chorus and comment. At the close, the prof has a breakthrough and finds the proof is actually fairly simple—at least for Higher Mathematicians.

Everybody is very serious and works very hard. They are all professionals; This is not Amateur Night—though one might think that from some of the costumes.

What could be seen as innovative in this new-old musical is its basic concept. But the format of the show in which it is developed looks and sounds very much like the formula musicals generated in Lehman Engel's BMI Workshop.

If anything has been gained by producing this, it should be the awareness that it's not a winning idea to set Heisenberg's Uncertainly Principle to music, even with Philip Bosco as Niels Bohr.

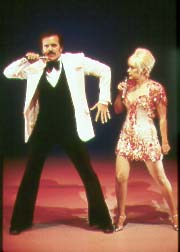

"Pete 'n' Keely" [***]

| |

| George Dvorsky & Sally Mayes in "Pete 'n' Kelly." Photo: ©Carol Rosegg, 2000. | |

The concept of the show is an acrimonious "Come-back" reunion on camera of two former TV singing-stars. Their ratings and lives have suffered severely since they broke up.

What saves this economically-packaged show at the John Houseman is its real stars, Sally Mayes and George Dvorsky. They are real pros, in great voice, and looking great as well!

They sing some durable standards—"Besame Mucho," "Daddy," and even "Battle Hymn of the Republic—as well as show songs written by the stage-director, Mark Waldrop, and the musical-director, Patrick S. Brady.

The format of the show—which its creators insist is a musical—is awkward, even amateurish, with the attempts to simulate a studio-broadcast intrusive.

What is really needed is Dvorsky and Mayes in a real cabaret act, singing and styling an entire evening of great songs. And not pretending to be Tina Turner & Ike, or Donnie & Marie, etc.

"A Child's Garden" [**]

No one would go with me to see this precious musical, based on Robert Louis Stevenson's childhood memories. Even though it is produced by the admirable Melting Pot Theatre, whose "Cobb" is currently such an outstanding achievement at the Lucile Lortel Theatre.Perhaps those I invited feared the lyrics would be adapted from RLS's "A Child's Garden of Verses"? If so, they were right.

Once upon a time, I knew all the verses: "Birdie with a yellow bill/Hopped upon my window-sill/Cocked his shining eye and said/Aren't you 'shamed, you sleepy-head?"

Then there was that bothersome Shadow, which went everywhere with me—and RLS—but what could be the use of him was more than I could see.

"Home is the hunter, home from the hill," however, has a chill about it. "Glad did I live/And gladly die/And I lay myself down with a will…"

The frame of this musical is a TB-doomed RLS, coughing in spasms in foggy San Francisco, penniless and unable to finish a commissioned story for his Scots publisher.

Four charming young performers recreate those magical summers on his grandfather's estate outside foggy Edinburgh.

Once again, everyone is very sincere, professional, and vital in performance. On the tiny stage, an evocation of the green hills of Mid-Lothian has been abstractly and ingeniously devised.

Much as I admire RLS's work—or is that nostalgia for childhood?—and his fight to write something of value before Galloping Consumption felled him, neither the actor-surrogate nor his memories really moved me. This was more like an illustrated lecture, with musical accompaniment. The tunes, in fact, did not make the lyrics more memorable. Or even more nostalgic.

"Christmas with the Crawfords" [****]

|

| Joan Crawford catches daughter Christina with a wire coat-hanger in "Christmas with the Crawfords." Photo: ©Pate Eng, 2000. |

But, set against all the shows above, it proved more entertaining than those which cost millions to mount and those which are burdened with Serious Purpose.

If you are in search of an hilarious holiday evening out, get down to Grove Street before the crowds! The place was packed the evening I was there, and the entire cast was in the tiny foyer after the show to greet the enthusiastic audience.

Created initially in San Francisco, the new version is "fresh as paint." Which has been laid fairly thickly on the faces of some major Hollywood Stars of the 1940s.

Joey Arias is a marvelous Joan Crawford, with a pompadour wig even more terrifying than the monumental hair of Ann Miller [Matthew Martin].

The show's format is a Hedda Hopper radio-interview on Christmas Eve from Joan Crawford's spotless Brentwood living-room. Joan's career is in a nose-dive, but she isn't going to let the world know it. Nor is she going to permit her children, Christina and Chris, to be less than perfect. Especially in front of Hedda and her Hollywood peers. All of the Crawford Horror Stories from Christina's best-selling "Mommie Dearest" exposé are hilariously recycled.

It qualifies as a musical because a parade of glamorous stars comes to Joan's portico, mistakenly thinking they've found Gary Cooper's Christmas Party next-door. With Hedda's open-mike, who could keep Judy Garland [Connie Champagne] from singing? Mark Sargent makes a triple-score as Carmen Miranda, LaVerne Andrews, and Ethel Merman.

Gloria Swanson wasn't known for her singing: "We had Faces!" But she takes her riotous turn, thanks to Trauma Flintstone, who also sings Patty Andrews. Bette Davis, as Baby Jane, drops in, as well as Shirley Temple, Edith Head, and Katherine Hepburn!

With a sidelong nod to "Forbidden Broadway," some of the Golden Oldies have had their lyrics adjusted for the Laugh-Meter. This is a great show, and not just for the holidays. But who wants to open Christmas presents in February? So see it now!

"The House of Seven Gables" [****]

The good news in Music Theatre is that the World Premiere of Scott Eyerly's new opera, "The House of Seven Gables," was a rousing success.The bad news, as usual, is that the handsome, haunting production—at the Manhattan School of Music—was presented only three times. It cannot be repeated nor transferred. That is the ongoing problem with all the outstanding opera productions at both the Manhattan School and the Juilliard School—which even has its own Opera Theatre.

Eyerly has based his impressive work on Nathaniel Hawthorne's classic New England ghost/mystery tale. Like Richard Wagner before him, he has devised both the libretto and score.

But, unlike many of his contemporaries who also create new works of Music Theatre, Eyerly has a very good dramatic sense. His opera is good theatre, as well as being presented through interesting and even haunting music and lyrics. Eyerly has a very good sense of character, mood, and action: all of which he is able to evoke in varied musical modes.

What's more, it was thrilling to rediscover the twists and turns of Hawthorne's plot, with a Missing Will and a Hideous Curse hanging over the Pynchon Family.

It was also gratifying to have the story unfold, as the characters reveal themselves in action and relationships, in a most effective series of arias, duets, and choruses. Eyerly does use dissonances for dramatic effect, but he is not about to punish either the singers' voices or the audience's ears.

The new work is so attractive and effective, it is sure to have more productions in the near future.

The last of the Pynchons in their ancient seven-gabled house are surrounded by its ghosts, unseen but sensed. Although the ghosts' clothes are clearly of an earlier time, these presences are initially a bit confusing. When they come momentarily alive, to recycle events from the past, all becomes clear.

An admirable achievement, strongly made manifest through the performances of James Schaffner, Christianne Rushton, Kelly Smith, Bert Johnson, and Dominic Aquilino.

Plays New & Old—

"Old Money" [****]

| |

| John Cullum and Emily Bergl in Wendy Wasserstein's "Old Money." Photo: ©Joan Marcus, 2000. | |

Was he Wasserstein's inspiration for the newly-rich Jeffrey Bernstein [Mark Harelik] in her new and nostalgia-rich drama, "Old Money"?

Jeffrey has bought a somewhat worn Wasp Mansion, restored it at immense cost, and now, he's invited the Movers and Shakers of Manhattan and "The Coast" to a gala party in the middle of August. He knows everyone who's anyone is in the Hamptons, but it's his test of his power that they will return to the city for his event.

In Old New York—as the novels of Edith Wharton so sleekly and satirically show—the really Old Money was that of the descendants of the Original Dutch Settlers and the adventurous English who followed. These people owned the land on which the Great City grew.

They were WASPS and they knew how to deal with the New Money Crowd, which might well include sons of emigrants, Italians, Germans, and even Eastern Europeans.

Wasserstein's play moves back and forth in time, showing another newly rich non-Wasp, Arnold Strauss [also Harelik], trying to move up the social ladder, in the very same mansion, when it was new and splendid. Being named to the Board of the Metropolitan Museum, then as now, is the Golden Ring. But the anti-semitism in the splendid room is palpable, and he misses the ring.

The Rockefeller children and grandchildren have devoted careers to giving away the ill-got gains of Robber-Baron John D. Rockefeller. In this provocative and strongly satirical play, the son of the original owner—another Self-Made Man, with all the rough edges intact—also disperses the fortune.

This leaves his son—played by John Cullum—by design with no inheritance. He becomes a professor, with a vast knowledge of the history of Old New York. And of his grandfather's house, to which he's now been invited by Jeffrey's rebellious son.

But Cullum also plays Schuyler Lynch—combining Dutch and English blood-lines—the architect of the mansion. He also represents the Artist who is a decoration—then as now—to the stultifying society of the rich.

As all the characters in the present are played by actors who become their own ancestors or others in the past, this proves somewhat confusing. But when characters from the present find themselves in the past—or vice-versa—and are treated as if they were people they don't even know, the added complexity is less Pirandellian than simply game-playing with the audience.

Mark Brokaw directed the excellent cast, which included Mary Beth Hurt, Dan Butler, Jodi Long, Emily Bergl, and Charlie Hofheimer.

Thomas Lynch—no relation to Schuyler—devised the magnificent mansion interior. In the fairly intimate Newhouse Theatre, it seemed quite as grand as the much larger one seen upstairs recently in the Vivian Beaumont for "The Little Foxes."

"Tiny Alice" [*****]

At the Second Stage, this revival of "Tiny Alice" is a handsome and very impressive staging of one of the recent American Theatre's most important but mysterious dramas. This production should do much to restore to playwright Edward Albee the admiration and recognition he deserves—but which has been so long lacking.Richard Thomas is amazing and moving as the lay-brother Julian, who is literally sacrificed to the God Unknown, the Alice whose spirit lives in a model-mansion replica of the mansion in which the action takes place.

Thomas' passionate, sensitive, but baffled Julian is a certain Tony contender. And not to be missed. As Albee presents Julian, he is selfless but intelligent, dutiful to the point of masochism, and both simple and complex. He has not sought nor achieved priestly orders.

And his passion to serve God is so strong, he could accept martyrdom. Which is in fact visited upon him by the surrogates of the unseen, incomprehensible "Miss Alice."

But this happens only after he has been tested—seduced, even—in degrees by the riches of the great house: the library full of rare books, the fine wines, the fabulous food, the creature-comforts, the riding of thoroughbred horses. And, finally, in secular attire, as Miss Alice's husband-to-be, Julian succumbs to the Ultimate Seduction. But the woman he believed he was wedding is only a surrogate.

His shining innocence has been compromised. He has been tempted by the vanities of this world—and surrendered to them.

In the original Broadway production, Julian was played by a weathered John Gielgud, not by a young man. Gielgud even demanded some cuts in Albee's text, noting that he couldn't play what he could not understand. Unquestionably, this casting and the cuts hurt the powers of the play.

Bill Ball's long-ago San Francisco ACT production was far more effective—and memorable—with an elemental set and Paul Shenar as Brother Julian. It remains one of the best stagings Ball and the ACT ever did.

Alan Schneider staged the Broadway premiere, in which the advance of the tiny Alice in the mansion-model—down long miniature corridors and staircases to her dying acolyte-husband Julian—was marked by the extinguishing of tiny lights in the replica as she progressed, otherwise unseen.

When her spirit—accompanied by a thunderous beating of a heart—reached the Library and the actual model, the stage was plunged into darkness. I was puzzled by this effect, for I thought Julian was experiencing a spiritual union with the Unknown God, even as he left the shell of his human body.

In Western myth and symbol, Light represents not only Knowledge, Truth, Enlightenment, the Good, but also the blinding Presence of God: The Burning Bush, The Pillar of Fire.

So I suggested to Alan that the lights in the model should go on, not out, as Alice progressed, and when the invisible, unseeable Presence entered the actual room, the stage should be filled with a blinding Light.

He told me that only Murray Kempton—who'd written wonderfully of the powers of the play—and I understood the Mystery of the drama. He invited me back to see the production again, and this time, the lights stayed on.

Even now, I'm not sure I understand Albee's own intent, but I have my own understanding of the drama—which works for me. And it certainly does in this production.

After the New York premiere, however, some critics thought Albee had lost it. What had happened to the brilliant young playwright of "Zoo Story," "American Dream," and "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?"

For many theatre-regulars, the play was incomprehensible. Some saw it as Theatre of the Absurd pushed beyond its limits: Absurdity for its own sake.

Some snide critics were certain "Tiny Alice" was homosexual code for a man with a very small penis. They were sure Albee was laughing at his audiences, goofing on them.

But I cannot forget the sage comment of Rosamond Gilder, founder of the International Theatre Institute and sometime Editor of "Theatre Arts." At the time, she dismissed the play as rubbish and nonsense. As a sad disappointment, considering Albee's "promise" as a Young American Playwright.

Six months later, she told me she and her sister Francesca were still arguing every evening over dinner about how stupid, empty, pretentious, and meaningless "Tiny Alice" was. She cocked her head and smiled slyly: "If it were really any of those things, it wouldn't continue to bother us. We cannot solve its riddles, but we also can't forget the way the play worked out. Nor that brilliant production."

Do see this equally splendid staging, in its minimally monumental production. It's staged by Mark Lamos and set by John Arnone. But at its thunderously beating Heart, it is still a Mystery.

"The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant" [**]

| |

| Petra von Kant weeps bitter tears at Henry Miller's Theatre. | |

Now it has been translated, reworked, and revived at the historic Henry Miller's Theatre. It may be the last show to play there, for only the facade is Landmarked.

Anita Durst—of the real-estate Durst Family, who control the rest of the block not now occupied by the Condé Nast Tower and ripe for major development—is fascinating as a mute design-assistant and semi-slave who worships the successful designer Petra. Not so long ago, Durst played a blood-drinking Hungarian countess in the Durst premises on 42nd Street, backing on Henry Miller's Theatre. In that, she was totally exposed. In this, she exposes only her talent. She's spooky as Marlene.

Petra, flamboyantly played by Rebecca Wisocky, is over the top in her emotions. She meets a young, calculating, selfish girl and promptly falls totally in love. She loses it as she tries to keep her new lover for herself. So she comes to a tragic end.

What's most interesting about this staging—aside from some near-bizarre performances—is the l950s Art Deco setting with bizarre Art Deco furniture and sculptures. Deco may have been dead in American in the Fifties, but not in Germany, which missed out earlier, owing to the appetite for monumental architecture of Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer.

Despite the ravages made by Xenon and "Cabaret" on the Henry Miller's interior, you can still enjoy the gilded plaster-work. Considering the need for more intimate Broadway theatres for both cabaret and small-scale shows—the Biltmore will return!—this handsome midtown theatre should be saved and restored!

See it before it's destroyed. And have a good laugh at Petra's expense. Somehow, I think Fassbinder would enjoy this production.

"Princess Turandot" [***]

|

| Italian Commedia stereotypes revived in "Princess Turandot"—without Puccini's music. Photo: ©Carol Rosegg, 2000. |

Or recall Julie Taymor's magical "The Green Bird"!

Darko Tresnjak is no Taymor, nor is his designer David P. Gordon. That has not discouraged either from creating their very own vision of Turandot and her three fatal riddles.

This is a Blue Light Theatre production in the McGinn/Cazale Theatre, above the Promenade. The space is intimate, the stage small, but director/adapter Tresnjak and designer Gordon have created a simple but serviceable and attractive milieu for the drama. It's also richly embellished with skulls and acrobatics.

The staging is an exercise in style, with the traditional Commedia characters setting the performance tone. It's worth seeing for the style alone.

You may not want to risk your life answering Roxanna Hope's riddles, however.

The functionary in the downstairs lobby continually referred to the show as "Princess Turandoh," as though she were a French princess. Or Goldoni were not an Italian. Both t's are hard in "Turandot." It's also hard to top Puccini…

Other Entertainments—

"Circus Oz" at the New Victory [****]

This zany Aussie Circus is the riotous, exciting holiday attraction at the New Victory on "New 42." It will perform there—complete with unusual acrobats and very strange New Age clowns—through January 14.As usual at the New Victory, the show is great for adults, as well as children. In fact, it has a sexual and sado-masochistic edge that may well go right over the kids' heads.

A very skilled acrobat—in masochist-leather and dog-collar—performs at the imperious behest of a Dominatrix with a real bullwhip. He's passive in everything but the skills of his performance.

There are special riggings and gadgets galore, but the heart of the show is the real talent of the gifted cast as acrobats, jugglers, and the like. Each has a fairly bizarre costume—some have changes—but even their clowning has an edge. And they don't keep it up on stage either: the audience is always fair-game.

Time was when New Yorkers—and kids especially—had to wait for Ringling Brothers-Barnum & Bailey to roll into town and set up house-keeping in Madison Square Garden. There was nothing like their five-ring circus, staged by John Murray Anderson. With Elephant Ballets.

Paul Binder's Big Apple Circus—now, as in every recent holiday season, in Damrosch Park at Lincoln Center—was the first to return to European circus origins with the one-ring circus. P. T. Barnum enlarged the arena to three rings. Ringling topped that with five.

Now in Bryant Park, there's now new competition for both Circus Oz and Big Apple Circus. This is Barnum's Kaleidoscape—not "scope," for some reason—which is also small-scale on the European model. Its tents make a colorful holiday display in this 42nd Street park.

What's more they are accessible to everyone, unlike the huge Fashionista Tents which regularly infest Bryant Park, as ordinary and/or uninvited citizens are shoved aside by designers, models, media, and celebrities.

The Parks for the People! It is wonderful that two important public spaces are currently hosting circuses everyone can enjoy! [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home |

reviews |

cue-to-cue |

welcome |

| museums |

recordings |

coupons |

publications |

classified |