GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, November 20, 2000

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] Tchaikovsky's "Orleanskaya Deva"

[03] Adolphe Adam's "Si j'étais roi"

[04] Riccardo Zandonai's "Conchita"

[05] Semi-Staged Operas in White's Barn

[06] Maurice Sendak's "Love for Three Oranges" at City Opera

[07] David Daniels in NYCO's New "Rinaldo"

[08] David Daniels in Munich's New "Rinaldo"

[09] New "Rigoletto" at New York City Opera

[10] Juilliard Opera's Fanciful "Cenerentola"

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

OPERA ABROAD AND AT HOME—

By the time you read this, the New York City Opera is already resting on its autumn seasonal laurels and preparing for its triumphal spring return to Lincoln Center. In Ireland's historic Wexford, they are savoring admiring reviews for their recent season of neglected operas.At the Metropolitan Opera, life & art go on, much as usual, but without much of the excitement and innovation which distinguish both the Wexford Festival and the NY City Opera. Unfortunately, your reporter is currently not able to tell you anything about the Met's new or old productions.

The Met's Press Department does not extend the press-privilege to websites—at least not to this one—preferring to see reviews in print in "hard copy." The Internet may be the Wave of the Future, but it has not yet washed up on the shores of the Metropolitan Opera.

At the Wexford Festival:

Three Virtually Forgotten Operas—

One of the world's more interesting and unusual opera festivals isn't staged in a national capital or even in a major cultural center. Instead, it occurs annually in a small but historic town on the Southeastern seacoast of Ireland. This is the ancient Viking center of Wexford—which still has some of its old city walls. In this Millennial Year, the October festival was explosively opened with a great fireworks display—and festive high-jinx—along Wexford's newly renovated harbor quay.

But this was only the 49th season of an opera festival which grew out of a local group of opera-lovers exploring works of opera-theatre unknown to them through lectures and recordings.

Next October will mark the 50th Anniversary of the Wexford Opera Festival. Unfortunately, all the funds Ireland set aside for Millennium Celebrations & Projects has run out. How can Wexford top this past fall's extravaganza?

The opening festivities need to be extra-special. After all, next year's forgotten operas were composed by no less than Antonín Dvorák, Jules Massenet, and Friedrich von Flotow!

The operas are Flotow's 1844 Alessandro Stradella, Dvorák's 1889 Jakobín, and Massenet's 1897 Sapho. Flotow's Martha—though not often performed—is still the best-known of his works.

Massenet has his day on the modern stage now and then in revivals—but not of Sapho. Dvorák composed some impressive operas—The Devil and Kate, for instance—but they are so closely linked to Czech tradition and culture, that they've not received the attention they deserve beyond Prague.

Next year could be the final season for Wexford's genial and resourceful Artistic Director, Luigi Ferrari, as well as its half-century anniversary.

This would be a great loss for the Wexford Festival, but Ferrari has regretfully already had to give up his post at the Rossini Festival in Pesaro. His good fortune has been to be called to Bologna's historic City Theatre to preside over its Opera.

As he told the press after the Wexford premieres this fall, the demands upon his time and energy there are such that he could no longer manage both Pesaro and Bologna. He is waiting to see how Wexford's needs can be adjusted to his new schedule in the city which gave sausage a distinctive Italian name.

Orleanskaya Deva—

|

| JOAN OF ARC AT THE STAKE——Lada Biriucov is a transcendent Maid of Orléans in the Wexford Festival production of Tchaikovsky's neglected opera. Photo: ©Derek Speirs/Wexford Festival Opera 2000. |

Unfortunately, he was neither playwright nor dramaturg himself. So his libretto was strangely and awkwardly cobbled together from Schiller and Jules Barbier and August Mermet.

What could have resulted had he based his opera on Mark Twain's account of The Maid makes fascinating speculation. Bernard Shaw's St. Joan was beyond his reach at that time, alas.

Fortunately, there are some extremely powerful musical moments—as well as some sensitively imagined ones—in Tchaikovsky's score. This makes any intelligent revival well worth the effort, despite the clumsiness of the drama itself.

Not so long ago, I saw a strangely surreal production of this challenging work in Munich at the Bavarian State Opera. So it is not exactly forgotten. And certainly not in Tchaikovsky's homeland.

The most outstanding feature of the Wexford revival was the powerful performance of Lada Biriucov as Jeanne d'Arc. The opera was sung in its native Russian, so the cast, including the admirable Youri Alexeev, Igor Tarassov, Aleksander Teliga, and Andrei Antonov, was largely in its natural linguistic and musical element.

Schiller has his St. Joan die a soldier's honorable death on the battle-field. But Tchaikovsky had enough sense of drama to realize—long before Honegger—that Joan of Arc at the Stake was what opera audiences really wanted.

He also included a fanciful—and somewhat mythical—romance on the field of battle. Joan has vanquished a Burgunian knight who is fighting against the Dauphin and his right to rule as King of France.

As she prepares to thrust her sword into his heart, the handsome Lionel looks into her eyes. And she is lost, lost in love and lost as the leader of her troops. This is no mere interlude, but a plot-complication with dire results. Not only to Joan, but also to the powers of the opera.

But Joan is destroyed as much by her own father—who till the end insists she's a witch—as she is by her English enemies and the love which weakens her belief in herself and her Mission.

Daniele Callegari conducted the score and cued the singers with vigor. In the small pit of the Theatre Royal were the members of the National Symphony of Ireland.

As stage-director, Massimo Gasparon was rather hampered by his set & costume-designer, Massimo Gasparon.

This peculiar paradox has been posed in the past when brilliant designers such as Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, Pet Halmen, and Rudoplph Heinrich have tried their hands at opera-staging.

Ponnelle finally succeeded—by subjugating himself as a designer. He soon realized he'd been trying to call attention to himself with his sets and costumes when he was only the designer.

Gasparon devised an elegant ensemble of Gothic architectural elements—including two-level structures—which could be variously combined to suggest major scenes. He also created handsome period costumes, complete with flowing gowns and billowing hairdo's for the ladies of the court.

On a large opera-stage, all this would have worked splendidly. Unfortunately, the stage of Wexford's Theatre Royal is all too intimate. The set-structures crammed the stage, and the gowns filled what space remained.

Movement was extremely difficult—and, as a result, it became stylized in a way that did not accord with the passions of the music.

The effect was rather like presenting the opera in subway car. The Coronation of the Dauphin in Rheims Cathedral could have been taking place in a corner of the Sacristy.

Si j'étais roi—

|

| TRUE LOVE IN OLD GOA——Joseph Calleja, as a fortunate former fisherman, accepts the love of a princess, played by Iwona Hossa in Adolphe Adam's "Si j'étais roi." Photo: ©Derek Speirs/Wexford Festival Opera 2000. |

Adam's comic opera is set in Goa—before it became a Portuguese Colony. But the costumes, palaces, and flora of this production wouldn't be out of place in a Hollywood version of Kipling.

What Barbe understands about designing for a small stage is the same thing ballet-designers have learned: Leave the center-stage open for movement! The venerable drop-and-wing two-dimensional solution to evoking locales worked very well for Si j'étais roi-which, after all, is both fanciful and stylized.

This King-for-a-Day plot—as devised by d'Ennery and Brésil for Adam—is at least as old as Calderón's Life Is a Dream. But it's much less serious in this treatment, in which a simple fisherman is put asleep, only to wake in the palace and be treated like the King himself.

In his brief rule, he rights some wrongs. And settles some scores.

But when he wakes, a fisherman again, he is baffled. Worse, his life is in danger. And the princess who loves him is to be married to the dastardly villain of the opera.

This delightful tale was staged and choreographed with charm by Renaud Doucet. It was conducted with wit and affection by David Agler.

Best of all, it was sung with delight, charm, wit, and joy by the entire cast. Outstanding was the Princess Néméa of Iwona Hossa. She is a fine artist who is sure to be more widely known on opera stages. Tereza Mátolvá, as the poor fisherman's dowry-less sister, was also impressive.

Joseph Calleja was both amusing and musically effective as Zéphoris, the temporary king. Darren Abrahams, as his village chum, was a comic delight—if a bit too frenetic. His work has already made an impression in a previous festival season: he's a young talent to watch!

Roberto Accurso was properly regal but humane as the King of Goa, threatened both by Portuguese invasion and betrayal by his deputy.

Dara Pierce and Emma Martin provided some light balletic moments. But Fiona O'Reilly was the major Coryphée.

Princess Néméa's brilliant coloratura aria recalled Lily Pons' famous showpiece, the "Bell Song," from Lakmé. But Hossa is better than Pons, who now is only a recorded memory.

i>Orientalisme was very fashionable in Paris—and other capitals, as well—in the late 19th century. It made its mark on painting, on decors, on furniture & fabrics, on poetry & fiction.

Some outstanding examples of these are now back in fashion. Has Luigi Ferrari sensed a trend in opera revivals?

Some seasons ago, Seattle & Portland revived The King of Lahore. How about a new look at Lakmé and Si j'étais roi? Then there's always Bizet's The Pearlfishers!

Conchita—

|

| CIGARET-FACTORY SINGERS——Not Bizet's "Carmen," but Zandonai's "Conchita." at the Wexford Festival. Photo: ©Derek Speirs/Wexford Festival Opera 2000. |

And, way back in 1984, James Levine conducted Zandonai's Francesca da Rimini, in an unnecessarily gargantuan production at the Met. A few seasons ago, this powerful work was also revived at the Bregenz Festival.

So Signor Zandonai is not exactly forgotten. But Puccini's undying sun does keep him, Cilea, Alfano, Giordano, and other eager Italian veristi eclipsed in the shadows.

Zandonai's courage in tackling Nobel Prize-winner Selma Lagerlöf's Swedish saga of the redemption of Gösta Berling is even today notable. It presented a subject, context, and a musical tradition completely alien to him.

Fortunately, Zandonai didn't choose to be folkloric.

Unfortunately, with his opera, Conchita, he was flabbily derivative. The work is based on a lurid fin de siècle novel of the now virtually forgotten Pierre Louÿs.

Called La femme et le pantin, this florid fiction for a time interested Puccini. But he finally rejected it, and Casa Riccordi passed it on to Zandonai.

Louÿs at that time enjoyed a vogue which today is almost impossible to understand. Obviously, both Riccordi and Zandonai thought they had another Carmen waiting in the wings.

Conchita is another of those fiery Spanish gypsy beauties who drive men mad with desire. She also works in a tobacco factory. In Seville, no less!

Why are so many operas set in Seville? Is it the sunshine?

In the Wexford Festival production, the factory girls seemed to be rolling cigars awkwardly or sorting tobacco leaves in big burlap sacks. During their rather boring workday—singing and sorting—the nobleman hero, Mateo, arrives to take a look at the operation.

He spots Conchita, who has already caught his eye, when, on leaving a convent, she got into a street-brawl, from which he saved her. That potentially interesting event, however, happened before the opera begins.

It would certainly have been more dramatic, more exciting, than the entire first act.

Mateo is hopelessly in thrall to the indifferent Conchita. He offers her a house, where he hopes to be with her. She takes the keys but locks him out.

He gives money to her impoverished mother, which infuriates her even more. She spurns and humiliates him, especially when he comes to see her dancing in a cafe, where she makes a point of semi-erotic contact with her guitar-player.

Only when Mateo is finally goaded so far that he slaps her and knocks her down does she realize how much he loves her. And how much she needs such a manly man!

What's more, she is still a virgin! She was only teasing Mateo with her musician.

Obviously, this opera is a seething cauldron—or olla podrida—of Political Incorrectness. It is also—in addition to its celebration of Spouse Abuse—dramatically and psychologically shaky.

The score's best sections are not even sung. There is a lovely symphonic interlude—almost a Tone Poem—which precedes Act III.

Zandonai would have done better to have treated the entire subject as inspiration for a symphonic suite. Or a Cycle of Spanish Art Songs?

For this opera to work at all on stage, it is absolutely necessary to have a wonderfully handsome and sexually magnetic Mateo who is visibly—and understandably—driven mad by the luscious beauty, sultry sexuality, provocative gestures, and contemptuous indifference of Conchita.

This was not the case in Wexford, sad to relate. Mateo was very careful of his vocal line, but it was passionless. He could have been a Master of Ceremonies at an opera workshop. He looked like a singing post in a blue suit.

The Conchita, alas, did not have the face, figure, or sexual allure that drives men to distraction and even to murder. Don José wouldn't have looked at her twice. She didn't even seem to be earning her wages at the cigar factory.

Zandonai's vocal demands were also difficult for this soprano. Her voice suffered from a metallic hard edge.

Conductor Marcello Rota did what he could to help these two leads, but the score itself is a long way off from Bizet.

The production was also booby-trapped by the complicated stage-filling set-design of abrizio Palla, which didn't leave much room for director Corrado d'Elia to maneuver his cast.

In the first scene, odd-shaped sloping platforms made the tobacco factory look like some kind of obstacle-course in which the girls could easily break a leg, leaping from one to another of these structures.

Soon, however, they were up-ended to reveal them as bulky wall-elements of a house, with illuminated insets of a Goya picture of women tossing a stuffed male-doll in a blanket. These weren't clear, unless one was very close to the stage.

It also wasn't immediately clear why they were on view in Mateo's house, now barred against him by Conchita and a huge ornamental iron gate. The gate could have been the Porte d'Enfer in Bohème.

Only when a collection of doll-puppets descended from the overhead grid was it painfully obvious that Mateo had been a virtual Puppet of Passion. In an earlier scene, he was tied up with ropes, but he didn't quite resemble a puppet in his actions.

Puppets! Wow!

What an ingenious underscoring of the score, the plot, and the production! Or is "painfully obvious" a better descriptive?

This was Luigi Ferrari's second Zandonai revival. At the post-premiere press-conference, some suggested that there are a number of worthy, if forgotten, composers and operas out there more deserving of revival than Zandonai.

This Wexford Festival production of i>Conchita was, if anything, anti-erotic. It reminded one of that famous Restoration Drama quip about a garishly costumed, coutured, and painted sex-starved harridan: "She is the positive antidote to desire!"

Andrew Porter, the magisterial British music-critic—formerly of The New Yorker—made me even more depressed during an interval of Conchita: "Did you know this was made into a movie starring Marlene Dietrich? The Devil Is a Woman, I think."

Opera Scenes & Concerts—

On a much happier note, semi-staged versions of Porgy and Bess and La Traviata were presented in White's Barn. There was also a Figaro which I was not able to see and hear.The beautiful Alison Buchanan was impressive as Bess—and also as a factory-worker in Conchita. Stewart Kemptser was a fairly effective Porgy, although he's not African-American. John Shea was music director.

The admirable Rosetta Cucchi served both that function and as stage-director for Traviata, which was affecting, thanks to the Violetta of Ermonela Jaho, the Alfredo of Ayhan Ardà, and the Germont of Roberto Accurso. Cucchi commissioned a series of interesting paintings by Federico Bianchi to set each scene.

In the vocal concert, Moscow-Paris Return, the historic cultural links between the two capitals—severed by the 1917 Revolution—were celebrated. Wexford took admirable advantage in this presentation of its slavic singers: Lada Biriucov, Katia Trebeleva, Igor Tarassov, and Andrei Antonov, with Valdimir Slobodian at the piano.

The talented chorus-master of the Wexford Festival, Lubomir Mátl, presented the Prague Chamber Choir in a Bruckner-Brahms-Martinu program.

At New York City Opera:

Three Exciting Revivals—

The Love for Three Oranges—

The fantastic stage-designs and outrageous costumes of children's book-illustrator Maurice Sendak usually upstage the rest of the show they are decorating.That would also have been so with Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges, had not the composer's libretto been as fantastic and bizarre as Sendak's designs for the New York City Opera production. The enthusiastic public reception of the recent performances at the New York State Theatre suggest that this handsome revival could be a welcome addition to the regular repertory.

Even if it had long been in storage, the production looked band-box new. Director Frank Corsaro's staging was also as fresh as an opening-night on Broadway.

But then his assistants were working with a new and youthful cast, willing to give Carlo Gozzi's strange magic fable their all. After an initial visual introduction of the two factions of the chorus—one clamoring for tragedy; the other, for comedy—they were heard, rather than seen.

This freed the forestage areas, at left and right, which otherwise would have been crowded with the jostling and noisy opera-lovers. Prokofiev may well have wanted them visible throughout the opera, to make his point about the impossibility of pleasing the public. Not to mention government censors.

But it's just as well they unseen, for they have in the past proved a tiresome distraction from the magical and idiotic wonders stage-center. But you still hear their cries of approval and distress.

In the NYCO's current revival, the carnival atmosphere evoked by Sendak's costumes and sets is—or was, as the fall season is just over—enhanced by jugglers and acrobats. Indeed, this production ought to be almost as much fun for intelligent young people as the Big Apple Circus, next door to the State Theatre in Damrosch Park.

Prokofiev's artistic conceit, in trying to please fanatics of both Comedy and Tragedy, results in a situation similar to that in Strauss' Ariadne auf Naxos. In both operas, an ensemble of stock Italian Commedia dell'Arte players are put through their paces. All the traditional character stereotypes are on hand.

Among the admirable performers were Richard Troxell as the hapless Prince, Linda Roark-Strummer as the evil sorceress Fata Morgana, Cherry Duke as her handmaid Smeraldina, Michael Lofton as Pantalone, Matthew Chellis as Trufaldino, and Eduardo Chama as the scheming Prime Minister.

The able George Manahan conducted with verve and enthusiasm, keeping the high-jinx bubbling but in hand.

Rinaldo—

| |

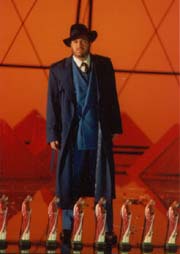

| JESUS WILL HELP YOU WIN!--Counter-tenor David Daniels as Rinaldo, a modern-day Mafioso, prepares to free Jerusalem from the Saracens with a row of plaster statues of Jesus. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

The New York City Opera, like its Bavarian counterpart, is leading an astonishing revival of interest in Handel's operas in modern performance. In Munich, the Giulio Cesare, Xerxes, Ariodante, and Rinaldo are variously so visually jokey and Post-Post-Modernist in performance that the NYCO Handel stagings seem reverently historical in comparison.

As directed and designed by Francisco Negrin and Anthony Baker, however, the new City Opera Rinaldo is sufficiently inventive and adventurous to exonerate it from charges of Historicism.

At least Handel's characters plot, cavort, lust, and battle for Jerusalem in semi-period costumes. It is possible to distinguish the Crusaders from the Saracens.

Admirable, in addition to Daniels, are Lisa Saffer as the lovely heroine, Almirena; Christine Goerke as the vengeful sorceress, Armida; Denis Sedov as the Saracen chief, Argante, and Kevin Burdette as the strange apparition of the Christian Magician. He's a kind of Merlin of the Middle East.

Harry Bicket, a genius with baroque scores, conducted as he did in Munich.

Rinaldo is, fortunately, one opera that cannot be updated by setting it in a Nazi Concentration Camp and invoking the unearned emotions of the Holocaust. That is too often done, however, with Nabucco, Samson & Delilah, and Fidelio.

It has become a stage-cliché which ought to offend even Jewish opera patrons.

The long-suffering Jews who survived in Moslem Occupied Jerusalem—both before and after the brief regency of the Crusaders—aren't even a footnote in Rinaldo.

But, in opera—as in American Presidential Elections—nothing succeeds like Excess. So it is only a matter of time before Rinaldo is presented as a melodramatic singing battle in the Gaza Strip, with Arafat instead of Argante leading the Moslem armies.

Rinaldo in Munich—

| |

| CHRISTIAN CRUSADER AS TV EVANGELIST!--Director David Alden puts a contemporary spin on Handel's "Rinadlo," a baroque opera about a mythical medieval crusade. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

Although the fabled action of Rinaldo takes place during one of the Crusades, director David Alden and designers Paul Steinberg [sets] and Buki Shiff [costumes] chose neither the medieval nor the baroque for their vision of this tale of true love sore beset, Christian fidelity, and Saracen perfidy.

Rinaldo [the brilliant David Daniels], dressed like a New York mafioso, wants to reclaim the Holy Land for Christianity along with his stalwart comrades. That they are a trio of talented counter-tenors makes this production a very special treat.

A fourth counter-tenor, Charles Maxwell, gets to play a drag-role and the Christian Magician, for which he's dressed like a fantastic Voodoo Conjure-Man.

Each of this interesting quartet of talents has a distinctive vocal quality which goes very well with the character being played.

Counter-tenor David Walker is properly brusque and conspiratorial as a Mafia Capo—Goffredo, the Crusader General. But Eustazio [counter-tenor Axel Köhler], his brother, is a wavy blond-haired Christian Evangelist, a real TV Bible-thumper.

In Alden's production, he is something of a cult-figure. At the close—with Jerusalem at last freed of the Saracens and in Christian hands—he's shown smiling but bound on the cross, rather like the Christ Crucified this summer at Oberammergau in the Passion Play.

It's all a send-up of the purported reasons for the Crusades. They weren't so much about Faith as about Power and Booty.

The initial setting is a room with walls covered with the symbolic Hand of Fatima. As these warriors are leading a Christian Crusade to liberate Jerusalem, this must be a Muslim stronghold they have already conquered.

In any case, it doesn't appear to be a very historic mosque, for, as with all the other settings, it is terminally trendy. The Magic Palace of the Saracen sorceress, Armida [Noëmi Nadelmann], is a seriously skewed travesty of a 1950s living-room.

A German critical colleague dated it 1970s, but its central floor-lamp could have been designed by Ray and Charles Eames. Not only was the room's perspective off-center and its yellowish floor steeply raked, but its walls were bold, clashing pink and orange.

A cut-out of the fleeing heroine, Almirena [Dorothea Röschmann], popped out of the stage-left wall to reveal the poor captive girl filling the cavity.

As often happens in such plots, the witch falls in love with Rinaldo, and her original lover, the Saracen King of Jerusalem, Argante [Egils Silins], is smitten with Rinaldo's Almirena.

The source of all these amorous, fabulous, and military high-jinx is Torquato Tasso's epic, Gerusalemme Liberatta. But what is this Holy City our Crusader heroes finally conquer for Christ?

It is a glowing sign on a high scaffold, spelling out Gerusalemme. An eagle—or is it a raven?—perches on the initial E. These letters are repeated on the floor, so large and solid that the characters can walk on them.

Between these two Gerusalemmes there stands a tall swooping slide, illuminated in neon, with three black cut-outs of girls—outlined also in neon—sliding downward.

When it's time to besiege the Holy City, Daniels and Almirena bring out armfuls of little plaster statues of Jesus. These are ranged across the front of the stage, and at one point they fall like a line of dominoes. Or the Radio City Rockettes, dressed as toy-soldiers.

This may be bad choice of image, for Christ is not defeated in this battle. Unless the production teams intends to underline the tremendous loss of Christian Lives in freeing the Holy City from the grasp of another of the World's Great Religions.

In the libretto, both Argante and Armida, defeated by the superior power of the Christian Crusaders, convert. This may have seemed a formulaic Happy Ending—along with the lovers reunited—for both Tasso's and Handel's audiences.

It parallels Shylock's forced conversion to Christianity in The Merchant of Venice. Alden forestalls any such triumphal Christian self-righteousness by making it very difficult for Argante to change religions.

In the final scuffle for Jerusalem, Argante—in full armor, with a big sword—is no match for Crusader heroes. His head is cut off at one blow. His body slumps to the floor.

Some distance away, his head continues to sing!

Harry Bickett, a protégé of Ivor Bolton, conducted with a full sense of the satiric interpretation, without losing any of the beauty of Handel's score.

What Handel opera seria will David Alden and friends choose for their next parodic spectacular? The four BSO Handel satires are, each in its own way, so provocative and attractive, one can hardly wait for the next installment.]

Rigoletto—

A fellow-critic warned me that I would not like this new NYCO production of Verdi's Rigoletto because it was designed to look "like the Wild West." Where he got either of those ideas is a mystery to me: That I would reject an updating. Or that designer John Conklin's settings were meant to suggest Arizona or New Mexico.Verdi in the Wild West would, I think, be an interesting counterpoise to Puccini's La Fanciulla del West. Interesting opera updatings—if they are Werktreu, or true to the events and atmosphere of the libretto and to the emotions in the music—are often a welcome re-introduction to an old favorite.

Dr. Jonathan Miller's famous Brooklyn Mafioso setting of Rigoletto, for the English National Opera some seasons ago, was received with jubilation by both critics and public. Both in London and New York!

In the event, Conklin provides a brooding outline of a medieval fortified tower in the background. Black against a deep red sky, this is Post-Modernist Minimalist Mantua, not the domains of the Duke of Albuquerque.

The only scene that is pure Futurist is the riverside bar & lounge of Sparafucile and his lovely but whorish sister, Maddalena. It consists of two slanted panels in front of the basic set elements.

If the strange slanted slashes in their surfaces look vaguely familiar to some opera-lovers who have been to Europe recently, no wonder. They look as though Conklin had lifted them right off the facade of Daniel Libeskind's new Berlin Jewish Museum!

What isn't Post-Modernist is Rhoda Levine's fairly routine, unadventurous, unexciting stage-direction. Given Gaétan Laperrière's rather pedestrian interpretation of Rigoletto, he could have used some fresh and vital ideas from his director. She may have had none to spare.

Given the conventions of this Piave libretto—based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse—it's understandable that the courtiers of the licentious Duke of Mantua would want to get even with this bitter, vengeful court jester who constantly mocks them.

What is often not clear in performance is why the Duke indulges and humors him, for Rigoletto's jibes and capers—as played and sung—seldom amuse anyone on the stage, not to mention in the audience.

Misha Didyk makes a devilishly handsome Duke, and he sings and plays the role with a sense of erotic entitlement. Both the Gilda [Christina Bouras] and the Maddalena [Kirstin Chavez] were making their debuts with the NYCO. Both were admirable, but evil always has the edge.

That made the Sparafucile of Peter Volpe even more attractive and impressive. George Manahan conducted, but he was not evil—or even in an evil mood—so this performance lacked a certain something in power.

At the Juilliard Opera Center:

A Charming Cenerentola and Her Prince Charming—

The new production of Rossini's La Cenerentola at the Juilliard School was, in effect, a pre-holiday treat. But—as with stagings of student singers at both the Juilliard and the Manhattan School of Music—it was impossible to extend it beyond its appointed three performances in the Opera Theatre. Those who think they know the story of Cinderella—complete with Fairy Godmother, Pumpkin Coach, and Glass Slipper—are suprised on their first exposure to Rossini's version, with libretto by Jacopo Ferretti.

There's no Fairy Godmother. Nor white mice transformed into horses for Cinderella's coach. Instead, Don Ramiro, Prince of Salerno, has a Merlin-like tutor, Alidoro, who helps him find the right woman to be his queen and mother of his heir.

Cinders' cruel step-father is the elegant, egotistical, blow-hard, Don Magnifico. There is no step-mother in sight.

The vain, unkind step-sisters, Clorinda and Tisbe, are hilarious grotesques—with music to match their pretensions.

Juilliard opera students usually already have some professional experience to their credit. Certainly this cast was eminently able, both as singers and actors. Jennifer Rivera was a sadly abused Cinderella, radiantly transformed into the future queen.

Stefano de Peppo was hilarious as Don Magnifico, well matched with his daughters, well sung and vividly played by Raquela Sheeran and Mariateresa Magisano.

Andrew Nolan's Alidoro was magisterial, but Don Frazure's Don Ramiro was a bit bland, rather than princely. When he disguised himself as his valet—searching for the unknown beauty he'd met at the ball—his body-language suggested that he might make a better Major Domo than a ruler.

On the other hand, initially disguised as the Prince, in search of a wife, the real valet, Dandini, made a fine prince in the person of Anton Belov. He has a wonderful zest in performance and a supple voice.

James Scott's elegant costumes really set the stage, more than the minimalist rake and screens of designerJuliana von Haubrich. Eve Shapiro staged rather routinely. Kenneth Merrill conducted. [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home |

reviews |

cue-to-cue |

welcome |

| museums |

recordings |

coupons |

publications |

classified |