GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, August 1, 2000

| |

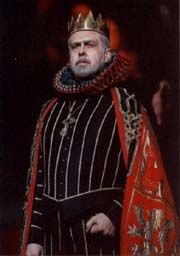

| THIS KING IS A KILLER!--Roberto Scandiuzzi as King Philipp II of Spain—the most powerful monarch in Europe—in Verdi's "Don Carlos." Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

[02] Munich Festival 2000

[03] Neumeier/Rose "A Cinderella Story"

[04] Jürgen Rose's "Don Carlo"

[05] Pountney/Lazaridis "Faust"

[06] Jonathan Miller's "I Puritani"

[07] David Alden's "Ariodante"

[08] David Alden's "Rinaldo"

[09] Peter Mussbach's "Fidelio"

[10] Deborah Warner's "Diary"

[11] Ballet Trio

[12] "Pariser Leben" at Gärtnerplatz

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

Picture of the Month!

| |

| HEY, GUYS! HAVE I GOT GREEN CARDS FOR YOU!--55,000 U. S. Green Cards up for grabs in German Lottery! Photo: ©Glenn Loney 2000/The Everett Collection. | |

The American Dream in Germany—

Win US Green Cards in the Lottery!

With Leica and lens ever at the ready, your roving reporter and Infotographer found this red-white-&-blue patriotic poster glued all over some German cities this past summer. It promises fulfillment of "The American Dream," no less! The poster suggests that the chance of winning one of the available 55,000 American Green Cards is "almost one in fifteen."

Anyone who has ever tried to get a Green Card in the United States—either for a newly arrived friend or for oneself—knows how very difficult it is to get one of these precious work & residence permits.

And yet, here in Germany, people are being urged to try their luck for one of the thousands of Green Cards the U. S. Government has put up for grabs. I couldn't believe the offer.

Similar—and much larger—posters on billboards suggested winning one as a way to overcome "visa problems" on visits to the United States.

A colleague at the German bureau of the New York Times assured me that this is no mere capricious give-away. Only those who meet certain criteria in education, training, experience, and expertise are eligible to compete.

Uncle Sam is looking for smart Germans to help with our millennial development plans.

And, as we drain off German brains, the German Federal Government is offering Green Cards to Asians who are skilled in computer-sciences to fill important jobs in the German economy.

Oddly enough, these are not called Grüne Karten, as one might expect. No, they are also called "Green Cards" in Germany. Indeed, all over Europe, this American phrase seems to have infiltrated native languages.

The Munich Festival 2000!

Not so long ago, the annual Munich Festival was purely a Bavarian State Opera festival, a celebration of the hits of the regular repertory and of striking new productions prepared specially for the festival—or being tried-out for the new fall season.When the late August Everding was in charge of all the Bavarian State Theatres, however, he conceived the idea of prolonging the seasons of the other Munich theatres into July. This permitted Culture-Vulture tourists to sample drama, comedy, ballet, modern dance, operetta, and musicals as well.

There simply wasn't time this July to see shows at the Residenz-Theater or the Theater der Jugend, both exemplary and well worth visits when you are in Munich. The famed Kammerspiele, the Jugendstil City Theatre, unfortunately, has been undergoing repairs, renovations, and expansions—from which it has not yet recovered.

Fortunately, the Bavarian State Ballet, the State Opera, and the State Gärtnerplatz-Theater provided a number of impressive productions. These filled all the available performance-slots in my program when I was not checking out the new Ludwig Musical Theatre near King Ludwig II's fairytale castle, Neu Schwanstein. Or going into the Bavarian Alps as I have done every ten years since 1960, to see the famed Oberammergau Passion Play. These reports have their own files on this website. Munich is already long enough!

The Prokofiev/Neumeier/Rose Cinderella Story

| |

| WHAT HAPPENED TO CINDERELLA'S UGLY STEP-SISTERS?--Here's one of them—Lisa Cullum—looking absolutely fabulous and whirling up a waltzing storm at the Prince's Ball, in John Neumeier's Munich "A Cinderella Story." Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

In Neumeier's handsome version, Cinderella's two thoughtless sisters [Irina Dimova & Valentina Divina] are really very beautiful, stylishly dressed, and they are also graceful dancers. Any prince might be satisfied with either, except for their vanity and superficiality.

But then Princes—either in fairytales or ballets—are not notable for their intelligence or insight. If fitting a shoe onto one of a host of local beauties is all it takes to find a wife, obviously the prince hasn't much going on upstairs.

In this ballet, Cinderella's magical shoes are golden, not glass. And she does her finest dancing, not in them, but in ballet slippers. So much for legends.

Neumeier has re-ordered the sections of Prokiofiev's Cinderella, which was commissioned for the Kirov Ballet in 1941, even as the Germans were advancing on Mother Russia. It was completed only in 1944.

The reshuffling seems to work very well—especially if you don't know the original score by heart. Neumeier has even added some other Prokofiev works: the symphonic poem, "Dreams," and the symphonic sketch, "Springtime."

The additions give the Prince [the excellent Alain Bottaini] more dimension, more opportunity to reveal his inner character and outer behavior through dance, than was possible in the original. This is an alienated prince, an Outsider.

In fact, deep characterization was not really a concern in the original choreography. It was only a lively, almost jazzy, retelling of the old tale, without much interest in Freudian sub-texts.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Prokofiev went abroad, visiting Japan, Bavaria, and America, where he was entranced with the Jazz idiom—which shows in this score.

So Neumeier has set it in a kind of magical white world of High Society between Two World Wars. Elegance is the key in much of the costuming, with Flapper Styles and handkerchief-gowns much in evidence. In the great court ball, these gowns float and fly with the graceful women, supported by white-tie-and-tails partners.

If Handel and Rossini could borrow from their own earlier works, Prokofiev had great models to emulate. So he included the major theme from his 1919 opera, The Love for Three Oranges.

Neumeier has wittily set this music as a diversion at court when a plate of oranges is offered to the ball guests. Oranges are passed from dancer to dancer with great ceremony and enjoyment!

To distance his Cinderella Story from more traditional balletic versions, Neumeier presents the Prince as an amateur artist, uninterested in life at court, He wanders the countryside, sketching from nature.

His drawing of Cinderella [demurely danced by Maria Eichwald] obsesses him. So much so, that he has no interest in the procession of local and exotic princesses his father the King produces as potential wives.

Cinderella's handsome young father [the elegant Norbert Graf]—while he does care for her—is obviously and understandably smitten with the beautiful new wife [wickedly and spiritedly danced by Judith Turos] he's won. So very soon—too soon for Cinderella, certainly—after the funeral of Cinderella's mother [Sherelle Charge].

At the grave, Cinderella plants a tiny hazel stalk. It grows and grows during the ballet, until it is a great tree in which she hides, to be discovered by the Prince.

At the ball, her step-mother shows her true colors by ignoring her husband and making a play for the King. Well, this isn't just the same old bed-time story.

Cinderella doesn't need a Fairy Godmother in Neumeier's version either. She has the memory of her mother to guide her and the support of four devoted Bird-Spirits to protect her.

None of this would seem so magically modern, were it not for the timelessness of the White World created by designer Jürgen Rose, who also designed the lovely costumes.

Rose has devised an enormous glowing white box for A Cinderella Story. He calls this a Magischer Lichtraum. Or a Magic Light-Space.

"The basic idea was to create a room or space which on one hand is a real room, but on the other hand represents a fictional space. It is its own world, in itself a closed Cosmos."

"No one notices that the room has no shadows. It seems so natural, that no one sees or asks where the light is coming from. An imaginary Magic Light is everywhere."

This is made possible by a double tent-construction—used also in Munich in some striking Mozart productions. The inner walls of the double-tent are made of "shirting," a thickly-woven but translucent cotton fabric. About 80 centimeters apart from this cotton wall is another outer wall made of tulle—the fabric of those stiff little ballet skirts.

Both of these fabric walls are sprayed on their backsides with black. Powerful stage-lights mounted outside the double-tent white-box are thus twice filtered. For Rose, this creates an indirect, doubly-diffused, unearthly light.

At the same time, this lighting-construction creates a new playing-area. An actor or singer can move between the two tent-walls. "He looks completely immaterial, a Memory, a Dream Image."

Rose's Magic Room is made even more magical and mysterious by the fact that it seems to have no end to it.

The sides and top of the white box—which has no perceptible back-wall—are slightly smudged with black near their upstage margins. This smudging merges into pure black, which in turn, merges with the black curtains farther upstage, into which characters can disappear. Or appear almost magically.

The ideal ballet environment sets the stage without encumbering it with scenery or props—which inhibit choreography and dancers. Rose minimally uses only a white table, some chairs, thrones, and the ever-growing hazel-bush, as needed by the libretto.

Color is provided by the costumes and characters in motion. The subtle indirect stage-lighting softens these colors. And it helps evokes the inner life of the characters and what they are experiencing.

Rose originally devised this production for Neumeier's Hamburg Ballet premiere in 1992. But it has been newly constructed for Munich.

Of this double-tent construction, he says: "The neutral, concentrated Light-Space is for me like a sheet of white paper on which I can sketch in black-and-white or with color. But [sketch] not only one-dimensionally, but cubically…grotesquely,

dramatically, or lyrically. "It's not like a stage-scene that gives a certain piece atmosphere, ambiance, or milieu. Instead, it's a frame, a Passepartout.

The real sketches are the characters in all their aspects and all their expressions. The focus is set on them. They stand in the burning center of this abstract and at the same time magical Light-Space."

The Verdi/Rose Don Carlo

| |

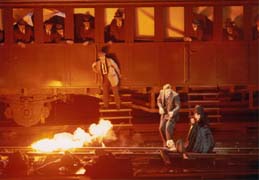

| BURN THE JEWS AND ALL THE OTHER HERETICS!--The Spanish Inquisition stages a human barbeque in Verdi's "Don Carlos," in a new production in Munich. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

The late Jean-Pierre Ponnelle was another designer-turned-director of equally wide-ranging—though different—artistic talents. Initially, as a designer—as Ponnelle himself admitted to me—his sets and costumes were much too detailed and complicated. He said he wanted to call attention to himself as a designer.

When he began staging, he found he had to force himself to work more simply. But at the close of his distinguished career, both his stagings and his designs were becoming more and more baroque in feeling, and even in appearance, on occasion.

Other brilliant designers—given the chance to stage operas in their own sets—have proved unimaginative, even disastrous.

Jürgen Rose, as a designer, has often given his director-colleagues sets and costumes which transform pedestrian stage-movement and lackluster Personnen-regie into memorable experiences at the opera.

Aside from the singing—which should be glorious—what's most often remembered about famed opera productions is their "look," which is largely made possible by designers and choreographers. Some noted directors are unable to move large crowds of chorus and extras effectively.

Working as his own designer, director Rose has been able to create an impressive and adaptable basic black-box setting for Don Carlo, which is almost the opposite of his white-box "Cinderella."

There are openings on all three sides of this grim box. They serve as doors, windows, and arches. In all the intimate scenes, the box is dominated by an immense Crucifix leaning against the stage-right wall.

Even though this confining space represents various chambers in the palace of King Filippo II of Spain, the Crucifix is ever present. It symbolizes the extreme religious fervor of the paranoid monarch—who fears God even more than his enemies—and the strong arm of the Spanish Inquisition, which dominates his state-craft.

King Philipp's El Escorial Palace, though very grand, must certainly—given the rigid ceremonial ritual of the Spanish Habsburg Court—have been something like a prison. This Rose's black box well symbolizes. Queen Elizabeth of Valois, Don Carlos, Princess Eboli, and courtiers and handmaidens were all under virtual House-Arrest.

Only Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa, was his own man—which made him so interesting to the immensely powerful but lonely and suspicious king.

To relieve the gloom of the Basic-Black Royal Room, Rose offers a glowing Fontainebleau scene and a memorable Auto da Fé. This horrifying Act of Faith climaxes with actual flames licking at the naked bodies of suitably agonized extras.

As his own costume and lighting-designer, Jürgen Rose is also visually able to reinforce the over-arching feeling of restraint and constraint in court and characters.

His triumph, however, is to achieve a degree of passion and human truth in the interactions of his major players which is seldom seen on an opera-stage. This was as fine as the finest of stage-productions of Schiller's tragic drama—of which I've now seen several memorable mountings.

That Zubin Mehta conducts surely helps the cast to sustain the dramatic power they achieve, not only through words and music, but also in pure human passion.

Even without the music, this production would still seem an impressive stage-work, because of the truth of the performances. But the truth about opera is that the music provides the players with the possibilities for emotional transcendence which can make opera-theatre much more powerful than drama.

This, of course, doesn't always happen, for a variety of reasons. Not least: hackneyed direction and routine conducting, neither of which were present in this Don Carlo.

As Filippo, Roberto Scandiuzzi, in this production, is a seriously troubled man. Not the monster he often appears in this opera. His concern for his empire—and his fear of his enemies—obviously outweigh his affection for his queen [Kallen Esperian] and consideration for his son, Don Carlo [Sergei Larin].

That Carlo was originally intended to be Elisabetta's husband—but has lost her to his own royal father, to seal the peace of the Wars of the Spanish Succession—is central to both Schiller's drama and the libretto.

He still loves her passionately, but she has such a strong sense of honor—now that she is effectively his mother—that she will not yield to his pleas. Princess Eboli's [Dolora Zajick] jealous betrayal of the queen, frustrated in her own love for Carlo, brings on catastrophe.

The King is crushed when he realizes that the queen doesn't love him. It's almost a harder blow than his own son's defiance and the rebellion in the Spanish Netherlands.

Paolo Gavanelli is a stalwart but independent Posa. Paata Burchuladze is imperious as the Grand Inquisitor. Over all the grim doings looms the figure of a mysterious Monk [Mario Luperi], who proves to be the spirit of the great Spanish Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Carlo V.

Don Carlo Production Preparations:

In TAKT, the house-journal of the BSO, an interview with both Rose and Mehta about the creation of this new production was titled: "Don Carlo, or Climbing Mount Everest."Rose notes: "The stage-space for my Don Carlo-staging is very reduced and black. In the process of working on the [Don Carlo] story, in the most diverse dramatizations, I've put my focus more and more on the spiritual background, on the inner conflicts of the characters.

"For five long days, I looked at Madrid, San Juste, and the Escorial. I went through endless flights of rooms which Philipp had built. Through the many pictures, furniture, and decorations, such little details, the historic figures came amazingly to life. So I could present the scenes of the drama in unusually plastic form…"

In this way, Rose believes he was able to come to understand the central significance—as well as the historical person and the fictional opera-character—of King Philipp.

"This monarch of the greatest empire in Europe and America had 30,000 masses said for the repose of his soul, in fear of the Last Judgment. The fear of what would come after death dominated him entirely."

Rose insists, despite his background research, that he had no interest in presenting Historic Tableaux. Instead, he wanted to show on stage the wrecked and miscarried relationships among the five major figures in Don Carlo.

But this was only possible if the flow of the action and the music was not interrupted by long scene-changes. That's why he designed his very simple and functional room, with its dark atmosphere as a foundation for the events. Only a few, but necessary, props were chosen.

Both Mehta and Rose believe it is essential to the flow of the drama that there is only one intermission. This helps clarify the importance of Carlo's memory of his love for Elisabetta in France and his depression over losing her. That's why it was also necessary to restore the often-cut Fontainebleau scene, to show how the dramatic conflict began.

But this is not only a drama about thwarted love, or deadly conflict between father and son. At the close, Don Carlo's passionate advocacy for oppressed people in the Spanish Netherlands leads to a local uprising, with the rabble calling for Carlos to lead them.

In the Rose staging, only the armed intervention of the Grand Inquisitor and his troops save King Filippo from a nasty confrontation and possible death.

In return, the Inquisitor demands Carlo's death—and in most productions, Carlo is either dramatically stabbed or shot. But then either his body or his spirit is redeemed by the spirit of his illustrious ancestor, Carlo V.

What actually happens at the close, says Rose, must remain a big question-mark. In some productions, the ghost of Emperor Charles V leads Don Carlo into his tomb. Or the voice of the dead emperor is merely heard from the imperial vault. In this production, the hovering Monk, with skull in hand, seems to be the Emperor's spirit, watching over the doomed prince from beginning to end.

Zubin Mehta makes it very clear that Verdi loved all his characters, "whether they were named Violetta or Carlo." Both Rose and Mehta have tried through the music, the emotion, and the action to make the characters believable and affecting to the audience as well.

Unlike some Munich Opera stage-directors, Rose had no intention of up-dating the opera. In fact, to make it more believable, he believes it was necessary to play it in a recognizable historical era: "Without imitating museum rooms and costumes of the time. But I think the silhouettes of the costumes and the establishing atmosphere of the stage-space must recreate something of this time of the great upheaval of 500 years ago."

The Gounod/Pountney/Lazaridis Faust

| |

| FAUST IS ON THE WRONG TRACK!--All Hell breaks loose in the avant-garde Munich staging of Gounod's French musical version of Goethe's German Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. classic. | |

The new Munich staging of Charles Gounod's Faust is only the latest and the most astonishing of all. If you think you already know this opera—or even Goethe's epic drama on which it is based—think again!

Without Gounod's well-beloved music to clue you, you might well believe you are seeing a bizarre social critique imagined by Anne Bogart or an extravaganza choreographed by Peter Sellars.

There are avant-gardist elements in this production which are virtual trademarks of some other famed directors and designers. But designer Lazaridis and director Pountney have brought them together to create an entirely new visual synthesis.

This makes Faust an epic 20th century panorama of War, Love, Betrayal, Death, and Redemption. The medieval Faustian ambiance of a German university town with ancient walls and half-timbered houses is only a faint memory.

Before describing some of the more striking scenes, it must be noted that the Munich cast was outstanding—one of the best ensembles assembled in years. Otherwise, their brilliance as singers and actors might seem only a postscript to a catalogue of visual wonders.

Marcelo Alvarez is an amazing young Faust, with a pure clear tone that is thrilling and produced without apparent effort, despite the tremendous demands made by both the score and the emotions provoked by it. And by Pountney's vision of the character. As a kind of latter-day Elvis in sleek sports-jacket—it lacked only "Hard Rock Cafe" on the back—he is a heart-breaker.

John Tomlinson is a sexy but mature Mephistopheles, seducing his prey with glee but also holding himself a bit aloof from the mayhem he manufactures. In the first of the production's two parts, he's like a Master Magician in a crazy cabaret.

In the second half, he has aged severely, now an old man with long white hair. At the close, in the hurly-burly of Marguerite's damnation and death, he's confined to a wheelchair.

In effect, he has relived the horrors of the twentieth century, trying to tempt Faust with earthly joys and win his soul for the regions of Hell. What is most surprising about this Pountney/Lazaridis version, however, is that both Mephistopheles and Marguerite ascend heavenward at the close—in the actual wheelchair!

Angela-Maria Blasi is a compellingly attractive and innocent heroine—with a lovely voice which is entirely equal to the transports of love and the terrors of the damned. In the extremities of Marguerite's desperation—abandoned by Faust and tormented by her neighbors—she is never shrill, but her voice affectingly suggests the tremendous fear and horror she's experiencing.

Instead of drowning her unwanted baby—as Marguerite does in Goethe's version—she has almost absent-mindedly thrown the babe into the huge refrigerator in her 1950s vintage chrome & formica kitchen.

Later, when her Kindermord crime has been discovered, she takes refuge in the fridge, but black hands of the Devil's helpers punch through the interior walls to grab at her. She fends them off.

This is a very modern Faust indeed. When Faust first sees her, instead of spinning wool thread at her spinning-wheel, she's mindlessly watching the rotary drum of her washer-dryer roll around and around.

Heidi Brunner's loving Siebel is both ardent in affection for Marguerite and wonderfully comforting in her abandonment and distress. Rodney Gilfry is a macho Valentin, as eager to kill his sister's seducer as he is the enemy on the battlefield. He has no pity for his poor sister—only fierce anger that she has sullied the family name.

Marita Knobel makes Marthe Schwerdtlein the quintessential modern shopping-mad busybody. She is no Martha Stewart, but she's more than a handful for Mephisto! Gerhard Auer is an able Wagner.

Conductor Simone Young's concentration on the score and her close support of the singers keeps the narrative in focus, despite the frequent turmoil all over the stage. Near the close, when there are four Marguerites on stage, each with a baby, it's not easy to know which is the real one.

The production-team of Pountney and Lazaridis are joined in this memorable Faust by costume-designer Marie-Jeanne Lecca. Not only has she created scores of handsome 20th century styles for the principals and the large chorus—with a number of changes, from scene to scene—but she has also, with Stefan Fichert, created hand and rod-puppets which reproduce the cast in miniature.

This is not just a cute gimmick—it certainly is that as well—but the puppets are essential to the vision of this production. After all, this is an opéra comique, with spoken dialogue instead of recitatives.

For more than a century after the opera's creation, German opera-houses insisted on calling the work Marguerite, instead of Faust. In the view of some Pan-Germanists, Gounod had not only changed the focus of the drama, but he had "Frenchified" it as well.

This new production tries to find a middle ground between Goethe and Gounod, between German and French sensibilities.

The singers and chorus are brilliantly faithful to the French libretto of Barbier and Carré. As are the puppet-actors to the spoken text, which is briskly uttered and sputtered in German, not French. The contrast and clash of sung French and spoken German is strikingly effective, especially in high-lighting the baser emotions and motivations.

All the puppets have individual handlers, dressed as look-alike functionaries or ordinary people. They respond, or react, to the puppets they animate, giving an extra dimension to the drama—often a comic one.

A Brechtian half-curtain is pulled across the forestage frequently to provide slits for puppet appearances or an upper-level for action and the siting of Marguerite's tiny chalet, with smoke spiraling from its mini-chimney

Mephisto's elegant sword-cane is even topped with a Mephisto puppet-head.

When Marguerite's former friends—the village girls—come to mock and scorn her, each has a baby-puppet on her right hand.

Among the visual astonishments are two sets of railroad tracks running across the downstage area. Down front throughout the production is one track which is used intermittently for a large hand-car, operated by pumping a handle. At the close, Faust's body is dumped into it, on top of a heap of black plastic garbage-bags.

Marguerite's bed, on rollers, also runs on this track, complete with large wooden ties, over which the cast has to clamber for its curtain-calls.

Slightly upstage of this track initially is another, on which stands a pre-war second-class railway passenger-coach. Part of another coach is seen attached to it stage-right. These are both played to great effect.

This visual astonishment is not original with Lazaridis and Pountney. Luca Ronconi used it two years ago in Salzburg for his Mussolini-Modern production of Mozart's Don Giovanni. All of the Don's varied sexual conquests appeared at the coach's windows to greet him.

I asked Pountney about this in Bregenz, where he was staging Rimsky-Korsakov's The Golden Cockerel. He was very ingenuous, professing to know nothing of the Salzburg staging, and insisting that lots of product8ions are using trains now.

Instead of presenting roistering university students drinking in Auerbach's [medieval] Cellar. Pountney has a gaggle of young business-men in suits with briefcases extolling the virtues of drinking from the windows and doors of the "Faust" Express.

A row of seats—as in a cinema—rises behind the railway coach, complete with chorus. Then, above this rise three swinging ferris-wheel seats, suspended in space, with cheering, waving women in them. At that point, there are four levels of action and song center-stage.

Later, the ferris-wheel seats are equipped with hair-dryers, so the women can enjoy the view and get their perms set.

Mephisto strolls along the tops of the cars, very much the Master of Ceremonies of 20th century trends and fads. Among his innovations: the Kermesse is no longer a medieval Carnival. And the Faust Waltz becomes something quite new.

It is Shopping-Madness, as choreographed by Vivienne Newport. Exuberant villagers waltz round in a great circle, wheeling shopping-carts piled high with products. This is either an homage—or a direct steal—from Anne Bogart's recent theatre-piece on rampant consumerism.

Figures of inflated men and women plastic dolls—sex-aids, perhaps?—are mounted on scaffold-towers and rotated around the dancing crowd.

Much later, when Marguerite is made the butt of village scorn for her transgression, these figures are visually echoed by towering giant-puppets, like those still used in Belgian folk and religious processions.

Four of these giants wear bishops' miters. But the fifth wears a cardinal's red beretta. With a difference: red horns are sprouting out of it!

Is this what Mephistopheles hopes will win Faust's soul for an eternity in Hell? It is already Hell on Earth!

When Valentin answers his country's Call to Arms and when the army returns victorious, satiric modern images are used. Pountney has had the ingenious idea of letting little boys weave their way through the triumphant men, shooting at each other with toy guns. The Victory Chorus will never sound the same again.

The little boys lie dead among the ties of the railroad tracks. This image certainly gives the lie to the glories of war extolled in the chorus. And to Valentin's false courage and virtue, he who repudiates his unfortunate sister, instead of protecting her.

When Siebel seeks to gather flowers for Marguerite, he finds them on grave-plots. As Lazaridis has visualized this, hospital beds covered with green-grass undertakers' carpeting are wheeled on stage. Each bed is topped with a glowing cross. Corpses on the beds tear the petals from the flowers Siebel is trying to steal. Mephisto even has to romance Marthe Schwerdtlein on one of these grave-beds.

Later, the same beds, now stark white, appear in the Walpurgis Night scene. This is an elegant all-white evocation of a 1920s garden-party. Even though the costumes are all white, textures and sheens of fabrics, as well as jazz-age and extravagant cuts and silhouettes make this a Fashion-Show in Hades.

Now the railway coach appears upstage right, wrecked and gutted. At one point, a section of trackage runs down center stage for other wheeled apparitions: Faust on Wheels!

As astonishing as the visual effects are the virtuoso performances of the singer-actors. Instead of posturing and singing amid all the constructions, they are actively involved with them. Including pumping the handle on the railway hand-car and pushing beds around.

They react humanly to this bizarre world Pountney and Lazaridis have conjured up for them, rather than merely enduring it in order to sing their arias, duets, and trios. Unfortunately for the vaulting final trio, however, the stage is so strewn with wreckage and optical sensations that it's not easy to single out the singers.

Looming over the carnival and carnage upstage is a large clock-face to remind Faust and the audience that his time is running out. Ronconi also used a number of clocks—especially railway clocks—in Salzburg to warn Don Giovanni of the same thing. Faust's clock, however, beams light out from its translucent surface. At the close, the numbers glow ominously.

Hovering over the stage like great oval haloes are two loopy constructions which suggest fairground roller-coasters. They are very much in keeping with the Carnival in Hell atmosphere. One of them lights up. The other is trackage for the world's two largest clear plastic shower-curtains, used to stunning effect in various scenes.

When the Apotheosis of Marguerite and Mephistopheles begins—as the wheelchair rises high overhead—the two haloes slowly descend toward the stage, to heighten the effect of a Himmelfahrt—or ascent into Heaven.

There is this ancient idea that one day the once brightest of all angels, Lucifer, will be reconciled with God the Father. Redeemed and reclaimed. As is Marguerite in Faust I, and even Faust, in Goethe's Faust II.

But it's not part of Goethe's—or Gounod's—vision that Marguerite should go to heaven riding in the lap of an aged Mephistopheles. And in a wheelchair, no less.

As Hamlet said to Horatio—in a rather different context—so must Pountney have said to Lazaridis: "There are more things on heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy." But not in your stagecraft, right?

You two guys! What next? Handel's "Messiah" as a hip-hop rap-fest in Harlem?

The Jonathan Miller I Puritani

| |

| JONATHAN MILLER ACCESSORIZES!--Director Miller and designer Clare Mitchell have provided a gown for Edita Gruberova, as Elvira, which perfectly matches the setting for Munich's "I Puritani." Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

Isabella Bywater was given credit for the stage-design. But this could have been an unimaginative stock-setting from the 1950s, when Munich's neo-classic National-Theater was still a bombed-out ruin.

The action, such as it was, occurred in a large space with tall arcaded windows along each side and some fenestration on the upstage wall. It could have been the choir of a renaissance church, but—with the drop-in use of a front arcaded wall—it suggested both a cold church and an even colder castle.

But then Cromwell's fanatic Puritans smashed every stained-glass window, every religious image, every evidence of artwork and humanity they could get their hands on. So perhaps the barest of spaces was most appropriate for this musical melodrama of Love & Intrigue at the ill-starred beginning of the Commonwealth in England.

Fortunately, costume-designer Clare Mitchell filled the stage with grand 17th century gowns—Puritan ladies had fine gowns, even if they were largely grey or black! Male principals wore elegant court dress and on occasion armor. And of course there were soldiers!

The obvious directorial problems are, basically, how to fill the space with a large chorus. Or with only two or three soloists. A tenor and soprano look so very lost in the middle of an immense stage-space with nothing to do but posture and sing!

They were doing this on both provincial and major opera stages a hundred years ago. But they had no Jonathan Miller—or David Pountney—to help the singers develop their characters, their movements, and their interpretations of the music.

Not much is going on in the heads of Bellini's protagonists anyway, so someone like Miller is very much needed with these bel canto works. Of late, however, he seems to depend on the astonishments of his set and costume-designers for the look of such stagings.

This was visually boring. It was saved from musical boredom, however, by the formulaic passions of Lord Arturo Talbo [Paul Groves] and his beloved Elvira. She was awash in cascades of coloratura, thanks to the talents of the seemingly ageless Edita Gruberova.

An elegant, haughty, be-jeweled lady behind me hissed to her escort: "Isn't she much too old for this part?"

Edita/Elvira may not look Sweet Sixteen in this Munich production, but she can still deliver the goods. It was thrilling.

Paolo Gavanelli was also excellent as the angry Puritan General who expects to marry Elvira and execute his rival.

If you ever wondered what became of England's Stuart Queen, Henrietta Maria—after the Puritans cut off the head of her husband, Charles I—this is the opera for you!

At least when the Great Powers had finally vanquished Emperor Napoleon, at the Congress of Vienna, they made his wife Grand-Duchess of Parma. They didn't throw her into prison. But she was the Austrian Emperor's daughter, after all.

Henrietta Maria was not only French, but also Roman Catholic. No place for either in Cromwell's Puritan Commonwealth. In the opera, she's called the "French spy," and Lord Arturo nearly loses his life trying to free her.

Curiously, for a bel canto opera, after all the denunciations and death-threats, all ends happily. No one important dies, and Arturo gets his soul-mate, Elvira,

This could be a movie with Mel Gibson and Madonna. Marcello Viotti conducted. He would look good in a movie, too!

The David Alden Ariodante

| |

| WHAT AM I DOING UP HERE?--For Munich's revival of Handel's "Ariodante," designer Ian MacNeil has devised a stage-within-a-stage. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

The Bavarian State Opera has already had immense success with two of Handel's baroque operas: Giulio Cesare and Xerxes. Without the connivance of brilliant stage-designers, however, the visions of the director wouldn't have worked.

For Ariodante, designer Ian MacNeil has devised an all-purpose baroque chamber with a raised proscenium-stage in its back wall. None of the architectural detailing is complete, however. It looks either unfinished or disintegrating. The latter better suits the disastrous events which occur within it.

Overhead is an elaborately painted mythological vaulting. This is very much in keeping with the feeling of a court-theatre or a noble chamber. The vault descends for the second act, and the villain, Polinesso, does some of his dirty-work on top of the rough plaster dome.

This has the effect of letting the audience look behind the scenes—behind the glittering baroque interiors—at nasty realities. Even on the stage-within-the-stage, elegant pretension is stripped bare.

In a delicate court-ballet, with towering powdered wigs and exquisite costumes—also by MacNeil—one lady has her wig knocked off to reveal her as a transvestite. She is then shoved about and thrown out of the stage-frame onto the floor below.

The contrast between elegant appearances and sordid facts is frequently emphasized visually. But, in this opera, "facts" are also not what they seem.

Although the libretto is based on an Italian work, Ginevra, principessa di Scozia, its dramatic origin is in Shakespeare's Much Ado about Nothing. Just as Shakespeare's poor heroine, Hero, is wrongly denounced at the altar as a whore by her intended groom, so also is Ginevra falsely accused.

In both works, the villain has his girl-friend dress in her mistress's clothing and then make love to him. In Ariodante, the villainous Duke Polinesso [Christopher Robson] entices Ginevra's lady-in-waiting, Dalinda, to don her attire and make love to him. She is hopelessly smitten, so she agrees, not thinking of possible consequences—such as being seen and overheard.

Polinesso wants to force Ginevra to marry him. He lusts not only for her, but also for her father's Scottish crown. Naturally, she has refused him, so he destroys her honor with his plot.

Her intended, Ariodante [Ann Murray], is so distraught at Ginevra's supposed sexual lapse that he jumps into the sea.

Having no further use for the pathetic Dalinda, Polinesso shoves her into the sea as well.

Both Ariodante and Dalinda survive, emerging from rolling baroque theatre-waves. These are a series of spiraling cylinders, cranked from the side, like those still in use in the 18th century Drottningholm Court Theatre near Stockholm.

In the meantime, the King of Scotland [Umberto Chiummo] has renounced his own daughter. Her shame seems about to break his heart.

Polinesso has Ginevra [Joan Rodgers] arrested, and she [both singer and character] is subjected to brutal maltreatment by lance-wielding soldiers. Dressed in rags and tied to a lance set across her shoulders, she is like a crucifixion victim.

She protests her innocence to no avail. If no champion appears to defend her soiled honor, she will be put to death. Ariodante's outraged brother, Lurcanio [Paul Nilon] has already challenged any knight who will dare to stand for the poor princess.

This resembles Elsa's need of a champion to defend her in Lohengrin, but that opera is much later than Handel's, of course.

Ginevra doesn't get a Lohengrin. Her declared champion is the detested Polinesso.

Fortunately, Ariodante appears in the nick of time to be her real champion, and Polinesso is fatally defeated. But not before he confesses his villainy, confirmed by the wet and bedraggled Dalinda.

The nobles wear metal breast-plates with period costumes, and the combatants don full armor, so most of the cast gets a thorough physical work-out.

Even though Alden and MacNeil have set their Ariodante in a fantasy baroque world—with a mysterious range of mountains inside the court-theatre—the action is roughly realistic, rather than daintily stylized.

Despite the artificial conventions of the plot and music, as well as of the ambiance, the sharpness of the denunciations and the strong physicality make the drama potent rather than static and formulaic. This is no mean achievement.

Polinesso is not only a nasty man, but his counter-tenor range is unpleasant to hear. This is not just an aspect of a bad character, though occasional raggedness could be taken as an excess of violent emotion. He seemed to have some difficulty getting through certain passages, as well.

Unfortunately, the radiant Ann Murray also had difficulty in one aria. She appeared to have insufficient vocal support in some crucial phrases.

Ivor Bolton—who has made a specialty of conducting period music on authentic instruments—helped the singers through very demanding vocal and physical challenges. His spirited conducting in the pit mirrored the vitality on the stage.

The David Alden Rinaldo

THE FOUR [COUNTER] TENORS!

| |

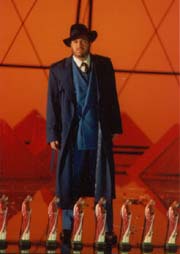

| CHRISTIAN CRUSADER AS TV EVANGELIST!--Director David Alden puts a contemporary spin on Handel's "Rinadlo," a baroque opera about a mythical medieval crusade. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

But it's not in the visual vein of Munich's mountings. And the NYCO can hardly afford a co-production with the Bavarian State Opera. So it will be interesting to see what the City Opera has done to or for Rinaldo this season!

Although the fabled action of Rinaldo takes place during one of the Crusades, in Munich David Alden and designers Paul Steinberg [sets] and Buki Shiff [costumes] chose neither the medieval or the baroque for their vision of this tale of true love sore beset, Christian fidelity, and Saracen perfidy.

| |

| JESUS WILL HELP YOU WIN!--Counter-tenor David Daniels as Rinaldo, a modern-day Mafioso, prepares to free Jerusalem from the Saracens with a row of plaster statues of Jesus. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

A fourth counter-tenor, Charles Maxwell, gets to play a drag-role and the Christian Magician, for which he's dressed like a fantastic Voodoo Conjure-Man.

Each of this interesting quartet of talents has a distinctive vocal quality which goes very well with the character being played.

Counter-tenor David Walker is properly brusque and conspiratorial as a Mafia Capo—Goffredo, the Crusader General. Eusaztio [counter-tenor Axel Köhler], his brother, is a wavy blond-haired Christian Evangelist, a real TV Bible-thumper.

In Alden's production, he is something of a cult-figure. At the close—with Jerusalem at last freed of the Saracens and in Christian hands—he's shown smiling on the cross, rather like the Christ Crucified this summer at Oberammergau in the Passion Play.

It's all a send-up of the purported reasons for the Crusades. They weren't so much about Faith as about Power and Booty.

The initial setting has walls covered with the symbolic Hand of Fatima. As they are leading a Christian Crusade to liberate Jerusalem, this must be a Muslim stronghold they have already conquered.

In any case, it doesn't appear to be a very historic mosque, for, as with all the other settings, it is terminally trendy. The Magic Palace of the Saracen sorceress, Armida [Noëmi Nadelmann] is a seriously skewed travesty of a 1950s living-room.

| |

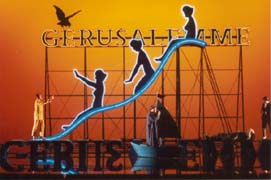

| JERUSALEM LIBERATED!--The Holy City as Luna Park in Munich's new production of Handel's "Rinaldo." Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

A cut-out of the fleeing heroine, Almirena [Dorothea Röschmann], popped out of the stage-left wall to reveal the poor captive girl filling the cavity.

As often happens in such plots, the witch falls in love with Rinaldo, and her original lover, the Saracen King of Jerusalem, Argante [Egils Silins], is smitten with Rinaldo's Almirena.

The source of all these amorous, fabulous, and military high-jinx is Torquato Tasso's epic, Gerusalemme Liberatta. But what is this Holy City our Crusader heroes finally conquer for Christ?

It is a glowing sign on a high scaffold, spelling out Gerusalemme. An eagle—or is it a raven?—perches on the initial E. These letters are repeated on the floor, so large and solid that the characters can walk on them.

Between these two Gerusalemmes there stands a tall swooping slide, illuminated in neon, with three black cut-outs of girls—outlined also in neon—sliding down.

When it's time to besiege the Holy City, Daniels and Almirena bring out armfuls of little plaster statues of Jesus. These are ranged across the front of the stage, and at one point they fall like a line of dominoes. Or the Radio City Rockettes, dressed as toy-soldiers.

In the libretto, both Argante and Armida, defeated by the superior power of the Christian Crusaders, convert. This may have seemed a formulaic Happy Ending—along with the lovers reunited—for both Tasso's and Handel's audiences.

It parallels Shylock's forced conversion to Christianity in The Merchant of Venice. Alden forestalls any such triumphal Christian self-righteousness by making it very difficult for Aragante to change religions.

In the final scuffle for Jerusalem, Argante—in full armor, with a big sword—is no match for Crusader heroes. His head is cut off at one blow. His body slumps to the floor.

Some distance away, his head continues to sing!

Harry Bickett, a protégé of Ivor Bolton, conducted with a full sense of the satiric interpretation, without losing any of the beauty of Handel's score.

What Handel opera seria will David Alden and friends choose for their next parodic spectacular? The four BSO Handel satires are, each in its own way, so provocative and attractive, one can hardly wait for the next installment.

The Peter Mussbach Fidelio

| |

| IS THIS A PRISON, OR A MAD-HOUSE?--The dark gloomy prison specified in Beethoven's "Fidelio" looks like a great mansion turned into an asylum in the new Munich staging. Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

He has already made an impression at the Salzburg Festival, and his Munich staging of Beethoven's Fidelio shows he's on track in re-thinking and re-imagining librettos and scores of operatic masterworks.

The old war-horses may never be the same, once Mussbach has worked them over. And opera old-timers may never recover either, unable to recognize their old favorites.

At least his Fidelio isn't so bizarrely modernist as the one David Pountney and Stefanos Lazaridis devised for the Bregenz lake-stage several seasons ago. That seemed to have been inspired by Magritte cloud-paintings.

Mussbach's Fidelio, for which he also designed the stage-environment, appears to be taking place in a grand old neo-classic mansion which has been turned into some kind of institution. More mad-house than prison.

If the Bregenz Fidelio suggested a tribute to Magritte, the Munich Mussbach mounting may be a tribute to Architecture. Stairs, pilasters, long halls: all suggest an abandoned grandness.

Fidelio/Leonore [Waltraud Meier] discovers her imprisoned beloved, Florestan [Stig Andersen], in what appears to be a rubbish heap hidden away in a back room.

This is refreshing change from discovering him in some Stalag in Dachau, or in a solitary cell in Auschwitz. Concentration-camp settings for Fidelio have become a stale visual metaphor over the past two decades. Nabucco and Samson often suffer from the same kind of Holocaust visual up-dating.

The off-white costumes of Andrea Schmidt-Futterer complement the spare neo-classic architecture. Long loose white coats for the men cover what could be sloppy late 19th century suits, though fedoras are an odd accent.

Curiously, thanks to the generic costuming and long blond hair, Fidelio doesn't look much different from Jaquino [Rainer Trost]. That doesn't necessarily mean she's very successfully disguised herself as a man, for Jaquino doesn't seem all that masculine.

The unfortunate Marzelline [Ruth Ziesak] hopelessly loves Fidelio, and scorns Jaquino. At the close, she has to settle for him anyway, so it's good he's almost a Fidelio look-alike.

Whatever the visual novelties—or excesses—of Bavarian State Opera productions, the vocal standard is always very high. In addition to the above-named talents, the staging was made memorable by the Rocco of Matti Salminen and the wicked Don Pizarro of Pavlo Hunka.

Beethoven's score was magisterially conducted by the BSO's General Music Director, Zubin Mehta

The Deborah Warner Tagebuch

The admired avant-garde British stage-director Deborah Warner didn't make much of a mark on Leos Janécek's "Tagebuch eines Verschollenen"—or Diary of One Who Vanished. But what can be done for a very short musical work which isn't quite an opera?For starters, you can have Nobel Prize-Winner for Literature Seamus Heaney make a new translation of the original text of Ozef Kalda.

Then, because Heaney's affecting text is in English—and the audience is largely German-speaking—you can have its less powerful German translation read by one of Germany's most famous, even venerable, actors: Thomas Holtzmann. This opened the evening in the lovely baroque Cuvilliés-Theater.

The program was padded-out with a sensitive performance of Janácek's 1. X. 1905, Sonata for Piano and "Im Nebel," played by Norbert Groh. He also accompanied the singers in Tagebuch.

In fact, he was part of Warner's quasi-staging, for a lusty peasant-lad [high tenor Ian Bostridge] was contorted under his concert grand at the opening. Some fitful video images of the fraught young man danced across an upstage screen. This is now known as Multi-Media Production.

Janácek's decent young farm-boy has fallen in love with a seductive gypsy-girl. Even though he calls her a whore, he intends to marry her—which will certainly cut him off from his own family and friends forever. Vanished!

The enchanting gypsy lass was impersonated by the sexy and radiant alto, Ruby Philogene. She wore Levi's with the knees cut out, which is less gypsy-style than hippie & drug-culture. [The knees are cut out—in case you didn't know—to make it easier to kneel. But not when you are praying! Ask Monica!]

They coupled under the piano, while Janácek's score played on. This surely must be a First?

Bostridge, with pipe and Brit jacket, looked more an Oxford don than a Czech peasant. Nor did his exquisite anguish come from a son of the earth.

Still, experiencing it was better than staying in the hotel. Or watching Meryl Streep teach all those New York ghetto children to play the violin.

Ballet Trio at the National-Theater

As if to demonstrate the versatility of the Bavarian State Ballet, a program of three modern choreographies was also shown in the festival framework.Once only a glorified opera-ballet—with one Ballet-Abend per month—the ballet, under Konstanze Vernon and now under Ivan Liska, has grown and matured into what is now virtually a world-class ensemble.

That may not be the perception of some balletomanes in the United States—especially the majority, who have never seen the Munich troupe. But studying the virtuosity of the various dancers in the three-part program reveals their varied excellences and their fine coordination in ensembles.

The three new ballet productions may well have been selected to demonstrate these skills. William Forsythe's the second detail was performed for the twelfth time, following its Munich premiere last December.

Forsythe premiered it almost ten years ago in Toronto with the National Ballet of Canada. Like the American choreographer John Neumeier, Forsythe seems to find a much more appreciative audience in Europe than in the United States.

Set in a gray-and-white box-like space—with stools upstage for dancers waiting their turns—this ballet is also costumed in body-hugging grays. This focuses viewer-attention entirely on the muscular bodies in motion, in repose, and in occasionally unusual contortions.

Not only does the choreography feature virtuoso individual moments—set in contrast to groups of three or four moving in concert—but it also emphasizes the Undulation Potential of the human body. It is wonderful to see so many dancers, standing in place or moving, animate their limbs and torsos with such fluidity. Almost serpent-like!

This is danced to a startling electronic score—with a strong beat and jazzy accents—by Thom Willems. Of necessity, the music is on tape.

The latter two ballets are performed with orchestra to scores by Igor Stravinsky. Conductor Markus Lehtinen gave both pieces brisk and powerful readings.

But the new Munich choreographies are miles removed from those originally conceived for the works. Stravinsky would surely be amazed.

| |

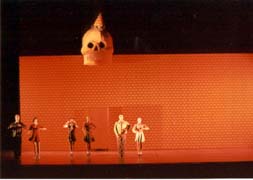

| WHO'S THAT LOOKING OVER MY SHOULDER?--Death oversees the frantic daily round of Twenty-Somethings in an updated Munich "Petrouchka." Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/Munich. | |

These are the limbs of the "extras" of the Bavarian State Opera, who take a full curtain-call for their later full-body appearances as ordinary men and women in the street. Sometimes they act as moving curtains to bring the actual dancers on and off stage.

This was the tenth performance of the new vision of Stravinsky's score. With Beate Vollack and Dirk Segersas sexy and athletic dancing young duo.

The mindless rush of commuters and office-workers—as manifested by the non-dancer extras—is transmuted in the choreography into something like a Ballet Méchanique.

Where the dancers in the Forsythe piece excelled in undulation, in this choreography, they excel in refining natural human movements into robotic exercises of great precision. The early morning rituals of brushing teeth and making ready for the day are reduced to essentials and briskly performed in synch.

The charming youthful ensemble included Olivia Jorba Cartoixa, Sherelle Charge, Cheryl Wimperis, Amilcar Moret Gonzalez, and Irene Steinbeisser.

The Russian roots of the music and its original folkloric fundus are somewhat suggested by the one huge scenic-prop. This is a long yellow rectangular free-standing wall, set on the bare stage with all the battens, catwalks, and overhead spotlights in full view. Set and costumes by Nigel Lowery; lighting by Mimi Jordan Sherin.

It is topped by an immense skull, with a jaunty yellow clown-cap on it, rather like one of those tower-tops on the Kremlin Wall. At one point, the grinning teeth of the skull open to drop a body on the stage. This is wrapped in lethal blue plastic bagging.

Soon after, three blue-bagged dancers fight their way out of the wraps to dancer-freedom.

The wall also has a number of openings, from which male extras can gawk at the preening sexy posturings of some of the lovely young ladies of the ensemble.

Initially, these windows open to reveal in each a copy of the Yellow Pages. Dancers seize these and immediately begin the rituals of dialing and chatting.

Toward the close, skeletal hands stretch around the wall at either side. And it rises in the air to reveal skinny legs which move it upstage. This effect is also rather Russian, like Baba Yaga's little hut which lopes around on chicken-legs!

The endless but enthusiastic repetition of the various rituals of daily-life are not so much celebrated in this choreography, as they are mocked. The mechanical and robotic precision demonstrated—backed by the Skull-Wall—suggests that Life is in fact a Dance of Death.

The third choreography—and the second Stravinsky—on the program was Saburo Teshigawara's Le Sacre du Printemps. While it certainly does suggest a rite and the sprouting of seedlings in the spring, Diaghilev would never have recognized it, save for the stirring chords of the score.

As with Forsythe's ballet, Teshigawara also created set, costumes, and lighting. The set is minimal: a three-sided white box, open in front, above, and at the rear. Dancers in form-fitting black—some with ridges down their backs, suggesting primordial dinosaurs or fish emerging on land—evoked an evolutionary birth and rebirth.

Where they undulated in the first ballet and moved mechanically in the second, here some also jerked and contorted, as if seized with fits. This is not an ensemble-effect, but is danced against the more supple and upward-thrusting movements of bodies which seem to be breaking through the ground, growing upward towards the sun.

This is quite a contrast to the Ritual Sacrifice of the original, so powerfully re-imagined in Pina Bausch's choreography of the score.

On the evidence of the two Munich Festival Nights of Ballet—and of new ballets in recent seasons—this ensemble is well worth a trip to the Bavarian Capital, even without a Night at the Opera.

Pariser Leben at the Gärtnerplatz

| |

| OUT OF MY WAY!--As the imperious courtesan Metella, in Offenbach's "Pariser Leben," Marianne Larsen sweeps past ardent suitors. Photo: ©Johannes Seyerlein/Munich. | |

This summer, the new hit American musical revival at the Gärtnerplatz was Cole Porter's Kiss Me, Kate. I wasn't able to see it, but local colleagues were ecstatic. I can well believe them, for this historic theatre—once entirely dedicated to the almost forgotten world of operetta—has a young ensemble which seems equal to any musical-theatre task, including lighter operas.

Jacques Offenbach's Pariser Leben—better known as La Vie Parisienne—featured some of the same actor-singers who scored in the Porter musical a few evenings before. It was the same the previous summer, when Bernstein stars distinguished themselves in Von Flotow's Martha—which is kilometers away from Bernstein and Broadway.

Young German audiences are not much interested in the old-time operettas their Opas and Omas loved. The librettos of some of those manufactured in Budapest and Vienna a century ago deal with a vanished world. One which existed in romantic wishful-thinking, rather than grim realities of daily-life.

Fortunately, the operettas which still attract wide audiences have some memorable and charming melodies. Offenbach's are chief among them, but even Franz Lehár hit the mark with Die Lustige Witwe. But then The Merry Widow is set in Paris, not in Budapest. There must be something very special about Paris and musical-theatre!

Stage-designer Kathrin Kegler has created a very stylish modernist vision of Art Nouveau Paris. The colorful, elegant, at times, outlandish, costumes of Marie-Theres Cramer wouldn't look out of place in a Broadway revival of Man-about-town Gardefeu—stylishly played and wittily sung by handsome young Marko Kathol—is angry with his demimondaine mistress, Metella—Marianne Larsen, also Kate for Cole Porter! So he's decided to romance beautiful married women instead.

He has contrived to convince a Swedish noble couple that he has been sent from their grand hotel to meet them. The Baroness [Christine Rohsmann] proves a stunner, and the Baron [Wolf Brannasky], a rich old gaffer—with a letter from a friend to Metella.

Gardefeu plans to give the Baron a high old time, while keeping him away from his wife so Gardefeu can make amorous advances. Obviously, he can't do this at the real hotel, so he has his servants pretend his home is a dependence of the hotel.

As in the best of Feydeau farces, Gardefeu is at his wits' end to keep his deception from being discovered. As the Baron is having a very good time, he doesn't mind. But the Baroness is not about to let Gardefeu have his way with her.

There are some traditional operetta comic routines along the way, but director Chris Alexander has managed to make them no more obvious than some of the comic by-play in Kiss Me, Kate. Which—being borrowed from Shakespeare—is even older than the oldest of operetta gags.

The vitality and enthusiasm of the ensemble for the story, the music, and their roles were impressive. It could have been First-Night, not the 31st time the cast had sung and acted this show.

At the close, not only the dancers, but also the chorus and principals joined in a lusty Can-Can. In the pit, conductor Roland Seiffarth seemed to be enjoying the production—and his orchestra's contribution to it—as much as the enthusiastic audience. [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home |

reviews |

cue-to-cue |

welcome |

| museums |

recordings |

coupons |

publications |

classified |