GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, July 20, 2000

| |

| BREGENZ'S BIG SKELETON--A photo similar to this one—of the Bregenz staging of Verdi's "A Masked Ball"—appeared in major media around the world last summer. Photo: ©Glenn Loney 2000/The Everett Collection. | |

[02] David Pountney's "Golden Cock"

[03] Dance of Death on Lake Constance

[04] Slashing Arts Subsidies

[05] Timely "Of Mice and Men"

[06] Steinbeck's Social Relevance

[07] Threats from Vienna?

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

THE BREGENZ FESTIVAL IN ITS 54th SEASON—

With the Vienna Symphony in Its Centenary!

A Golden Rooster & A Macabre Skeleton Foretell Doom:

Rimsky-Korsakov's The Golden Cockerel & Verdi's A Masked Ball

The Image Seen Round the World—

The Immense Skeleton Dominating the Bregenz Lake-Stage

This skeleton is one actor who did not take the winter off in Austria's festival-city of Bregenz. He loomed over the broad outdoor opera-stage on the edge of the Bodensee even through the worst of storms and snows. This is my own version of the Picture Seen Round the World! When the Lake Constance [Bodensee in German] production of Verdi's A Masked Ball opened in Bregenz last July, this view of the stage and the skeleton was reproduced in newspapers and magazines worldwide.

The production was—as is usual in Bregenz—stunning. But it wasn't the excellence of the actor-singers in the cast, nor the ingenious stage-direction that won the Bregenz Festival international attention last summer.

It was, quite simply, this enormous, brooding stage-prop. Death has been standing guard on the lake ever since. And he may have scared Bregenz kids on their way to school some dark January mornings.

The Bregenz stage and sets stay in place between the two summers of each lake-staging. After some repairs caused by a year's exposure to the alpine elements, Death is back in business. He's silently warning the 18th century Swedish King Gustav III Adolf that the monarch is engaged in a literal Dance of Death. From which he will not, can not, free himself.

What immense and overwhelming image will the Bregenz Festival be able to conjure up next summer? Worldwide picture-coverage depends unfortunately on an astounding image, not on artistic excellence.

The opera chosen for the Bregenz Summer 2001 lake-staging is Puccini's La Bohème. Death also looms over this opera. Poor Mimi is coughing herself to death with galloping consumption.

But the little seamstress and her starving-artist friends lived in cramped attic-quarters in Paris' 19th century "Bohemia." Can the same design & direction team—Antony McDonald & Richard Jones, who devised Bregenz's giant skeleton—create something equally memorable for the new lake-staging?

The late, great Jean-Pierre Ponnelle did this for the San Francisco Opera by creating an immense cast-iron stove to emphasize the poor artists' desperate craving for warmth. And for food, drink, love, and success…

It's very important that the Bregenz team devise something sensational. Something more memorable even than their Lake Constance skeleton. Not only will Bohème run for two summers, but every one of the outdoor amphitheatre's 7,000 seats needs to be filled every night the show is performed. It's not just a matter of, as the British say, "bums on seats," but also of artistic and economic survival.

More of this later—after a survey of the current productions.

David Pountney Gives Rimsky-Korsakov a "New Look"—

The Golden Cock Is Not What You May Have Thought

| |

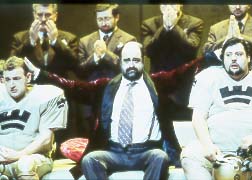

| THAT'S MY BOYS!--King Dodon's two idiot sons—generals of his army—are costumed as football-captains in David Pountney's updated Bregenz staging of Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Golden Cock." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival 2000. | |

His name is not mentioned in various program-listings because he doesn't sing at all. Instead, Maya Boog utters his warning cry of danger, out of view of the audience.

In Rimsky-Korsakov's satirical fairy-tale opera, this Golden Cock, Cockerel, or Rooster, is a magical bird who is supposed to warn his owner of impending danger. In the final moments, however, after all is lost for poor, fat, foolish King Dodon, the enchanted rooster kills the King.

Baumann is a talented actor-dancer-acrobat who trained both at the Salzburg Mozarteum and in New York at the Juilliard School. His wonderful twirls and turns high above the stage recall those aerial swoops and swirls of the demented Demon, in a recent indoor Bregenz staging of Anton Rubinstein's Der Dämon.

The opera-title—it's rendered Der Goldene Hahn in German—and that of Pushkin's satiric poem indicate a golden costume for this dangerous fowl. But in the new David Pountney production, the design-team of Huntley Muir [Sue Huntley & Donna Muir] have clad the Cock in a sleek green, body-hugging suit, with a red cockscomb. At least they have given him some golden stripes and gloves.

Traditionally, the Bregenz indoor production—unlike the two-season lake-staging—is given only one summer and is of an unjustly forgotten or neglected opera. This particular opera is hardly forgotten by some, however.

I have vivid memories of a colorful production of the opera at Lincoln Center, in the New York State Theatre. It starred Beverly Sills as the mysterious Queen of Schemacha. [Which sounds disturbingly like Shmatta.] The New York City Opera—of which she was then the reigning queen, later to become its artistic director—had surely mounted the fantastic work to show off her then brilliant coloratura.

In the current staging, the coloratura of the beautiful Costa Rican soprano, Iride Martinez, eclipses all memories of Beverly at her best. Martinez is a major talent—both as singer and actress—of whom much will soon be heard and seen. Her seductive singing is highlighted by her equally luring gestures and dance. No wonder King Dodon cannot resist her. To his mortal cost…

Festival Director Dr. Alfred Wopmann—who has an amazing talent for finding new young singers and giving them a showcase in Bregenz—says he first heard Martinez at the Hamburg Opera.

Also outstanding was the dependable Kurt Rydl as the bulky King Dodon, especially as he has to help sustain the fable onstage for more than two hours. At one point, he dons an Elvis get-up—or is he a Tango-King?—in a ridiculous effort to charm the enigmatic queen.

Alexander Pushkin's famous poem was the composer's immediate inspiration for this barely concealed satire of Imperial Russia. Czar Nicholas II was not exactly a model for King Dodon—read Dodo, or Dumb as a Dodo. But the meaning was clear, so the opera of course fell victim to the Imperial Censor. It was first performed only in 1909, after Rimsky-Korsakov's death.

For Americans—as well as Europeans—it should be of interest to know that Pushkin was not versifying some ancient Russo-Asiatic folktale. His sources, instead, were two of Washington Irving's short-stories in his famed Tales of the Alhambra.

Both Irving's and Nathaniel Hawthorne's stories have provided the opera-stage with a number of works, both old and new. Neither author obviously had any idea of devising strong opera librettos in their story-lines, but they are there, just the same. There is an enchanting modern Mexican opera based on Hawthorne's Renaissance Italian tale of a poisoned girl & garden, Rappacini's Daughter. Dr. Wopmann might well want to introduce this to European audiences!

Because The Golden Cock is a fairy-tale fantasy, with oriental overtones—which the score certainly emphasizes—an equally fantastic production would seem to be indicated. It invites such visions, the results of which could be most varied.

Instead, director David Pountney—already himself a Bregenz legend, with stagings of The Greek Passion, The Flying Dutchman, and Fidelio—has chosen a fairly tame modern vision of the fantastic Pushkin-Rimsky plot.

Replete with Playboy Bunnies—an homage to Hugh Hefner, apparently—and other 1960s and 1970s retro sex and style images, this staging looks a bit like those retro Broadway productions of, say, Footloose. Fortunately, the music is much much better. So are the performances.

Pountney's new Munich Opera staging of Faust also has a mixture of early and mid-20th century images—including Marguerite staring at a rotary-washer, instead of spinning at her wheel. Pountney may be in a 20th century nostalgia time-warp.

The customary excuse for a sensational visual updating of an old opera—especially one set in olden times—is that it is produced so often that audiences need to see it with new eyes.

Germany's Joachim Herz—himself a disciple of the late Walter Felsenstein, the High Priest of Opera-as-Theatre—is often outraged at such updatings. He regularly sends me his latest fulminations.

But he is angry only when updated productions are not Werk-Treu, or true to the work itself: the story, the characters & motivations, the locales, the era, and the score.

Frankly, though I am a great admirer of Pountney's ingenious stagings, I would have preferred more magic and fantasy than this production offered. The Harry Kupfer Bregenz staging of Rimsky-Korsakov's even more neglected The Invisible City of Kitehz did this with a an abstractly modernist vision that didn't look like the reception room at Bertelsmann Manhattan.

Instead of suggesting a fantasy, even bizarre, opulence of a crazy king & court, most of the opera seemed to be set in American board-rooms or sex-pits of West Side Manhattan motels. This didn't make the king's stupidity—or his draconian tyranny—seem more relevant. If anything, it diminished it.

There were even neon signs advertising [in English, not German] "GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS." Later, when the Queen was arriving, the neon changed to "FRAUEN"—a more mature lure for the amorous lustful King Dodon.

It was, in fact, encouraging to see any language at all spelled out on stage. Customarily, indoor productions have super-titles for operas sung in Italian, French, or English—sometimes in three languages, appropriate for an international audience.

But most of the Bregenz spectators come from Austria and neighboring Germany and Switzerland. So this opera—sung German and not always intelligible—this season didn't get super-titles.

There are never any titles or translations on the lake-stage, however. Projection of texts would prove almost impossible. Audiences read the synopsis and hope for the best.

For this Golden Cock revival, David Pountney and Nicola Raab drafted a new German translation—which could have used titles to advantage.

Oddly enough, there were laser-generated German titles for the songs of the Queen of Schemacha and her suite, as their texts were left in the original Russian. For some reason or other, possibly to emphasize her exotic and mysterious qualities.

These greenish-blue words danced across the upstage wall, sometimes flying apart, with letters scattering into the audience. A neat effect!

Everything in the opera is set in motion by a mysterious all-blue Astrologer [Eberhard Lorenz], who gives the eager king the magic rooster—for a payment to be decided upon afterward. Always a bad idea, in business or in politics.

Unlike the wonderful mechanical Chinese Nightingale—in that other neglected opera-fantasy—this bird is not for entertainment. He is supposed to warn the King of danger to the Nation and the Court. But he is in fact malevolent.

King Dodon is so obsessed with dreams of sexual excesses—egged on by the Astrologer—that he pays no attention to the warnings.

There are, of course, a number of amusing visual gags. The Royal Airlines is called Dodoflot—spelled out on the landing-ramp in Cyrillic letters, like Russia's Aeroflot. One of the royal princes arrives in a typical New York—or Hollywood—white stretch-limousine.

Finally, Dodon sends his two worthless sons—one immensely fat; the other a preening blond drug-sniffer—off to war. Their army is dressed in American football uniforms and does an athletic drills before departure.

| |

| DOUBLE-HEADER!--Head-on collision of King Dodo's two sons' sports-cars loses the war for sex-mad monarch. Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival 2000. | |

But they have already lost the field to the Queen, as Dodon has lost his heart to her. Or at least his loins, as he seems incapable of love, only lust.

She and her suite of lovelies tempt and mock him. The apotheosis—and the first indication of oriental fantasy—comes in the third act when a stunning cut-out of baroque swirls and Eastern Orthodox onion-turreted church-steeples descends from the flies. Where the Golden Rooster is still cavorting.

| |

| ONI0N-DOME ORIENTAL FANTASY--King Dodon and Court are astonished by entourage of mysterious queen in Bregenz Festival staging of Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Golden Cock." Photo: ©Karl Forster/Bregenz Festival 2000. | |

In the end, however, it's the Golden Rooster who knocks them dead—King Dodon, at least.

Kudos to conductor Vladimir Fedoseyev, who has greatly benefited the Bregenz Festival with his wide-ranging knowledge of Russian opera, music, and cultural traditions.

Praise also to choreographer Amir Hosseinpour, who has given the Bavarian State Ballet some remarkable choreographies as well. And honors to lighting-designer Mimi Jordan Sherin—also well represented also in Munich productions—for her ingenious uses of color, of light and shadow, to make the rumpus-room settings look more interesting.

Whatever the arguments may be in favor of modern updatings—often to make opera understandable to audiences unfamiliar with the works, by visualizing some imagined contemporary relevance—it's usually difficult, even pointless, to make such connections in terms of the actual period scores and period-libretto traditions. The basic love-stories or power-struggles and the characters involved may be ageless.

But the works themselves often are not. Medieval and Renaissance Codes of Honor, for example, mean little today. Today, Marguerite would hurry off to an Abortion Clinic. But Faustus—being, after all, a doctor of philosophy and fascinated by what passed for Science in his day—would surely have worn a condom!

Instead of selling his Immortal Soul to Mephistopheles, he would have taken a management post with Microsoft and Bill Gates. Now that is really relevant Up-Dating! But to achieve that kind of relevance, you have to rewrite the libretto and get Philip Glass or John Adams to rework Gounod's old-fashioned score!

Despite my own desire for a more ageless fantasy, I did find Pountney's production interesting, ingenious, and imaginative. But not very relevant.

I do not for a minute imagine Russia's new Czar, Vladimir Putin, as King Dodon. Anyone who has been highly placed in the former USSR's secret police doesn't need a golden rooster to warn him of danger. But, true enough, he could have used just such a fowl when he was vacationing as the crew of the Kursk died.

If Pountney had made Dodon look like Bill Clinton—especially in the sex-fantasy scenes—that might have at least looked relevant. But, as Clinton's term of office nears its close, he doesn't seem at any risk from a malevolent Golden Cock. Except perhaps his own?

On the Lake, the Dance of Death Goes Onward!

With the Bregenz Masked Ball production last summer, the British directing & design team of Richard Jones and Antony McDonald impressively demonstrated their ability to mount an opera with important but intimate scenes on the broad expanses of the largest outdoor lake-stage in the world.Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera—rendered as Ein Maskenball in German—aside from the culminating and fatal ball at the Stockholm Opera, is composed of smaller scenes. True, major opera-houses with major productions always manage to make King Gustav's visit to the clairvoyant, Ulrika Arvedson, into another crowd-scene.

As this scene takes place in a large floating coffin in Bregenz—where some kind of water-borne craft is always expected—not so many chorus can crowd in. But the stage is artfully decorated with naval and civil on-lookers. McDonald & Jones have devised a variety of ways—with the aid of choreographer Philippe Giraudeau—to keep choral and choreographic action moving across the vast stage.

With 7,000 spectators spread out before the stage-apron, it's very important that no viewer be very far from some kind of stage-action—even if it doesn't involve the principals. It's to be hoped, or rather, expected, that the team will invent even more astonishing stage-pictures for next summer's La Bohème.

Marco Berti proved a powerful King Gustav, with Elizabeth Whitehouse a most affecting Amelia, his beloved and the wife of his friend and counselor, Graf Ankarström, impressively sung by Pavlo Hunka.

Counts Ribbing and Horn, conspirators against the pleasure- and opera-loving King, are only too eager to enlist Ankarström in their plots, once he is convinced of his friend's betrayal of his trust and friendship. Arutjun Kotchinian and Hernan Iturralde were strong in these roles, given more importance in this production than is the custom.

Elena Zaremba was memorable as the far-seeing Ulrika—who in fact bears the name of King Gustav's mother, Sweden's Queen Luisa Ulrika, sister of Frederick the Great.

As the King's light-hearted page and devoted servant, Oskar, /strong>Elena de la Merced was a delight to see and hear. She looked and acted most becomingly boyishly—and surely must have won the hearts of many of both sexes in the audience.

Marcello Viotti kept the pacing taut and the climaxes cresting, conducting the excellent Vienna Symphony, now celebrating its 100th anniversary. This is not the older and more widely recognized Vienna Philharmonic—which is the Salzburg Festival's pit-orchestra every summer. But it is just as worthy of acclaim.

The Moscow Chamber Chorus was impressive in both major opera productions, but especially in the Rimsky-Korsakov work.

For the record, here is an edited reprise of a portion of my report on the premier last summer. This should provide a fuller explanation of the visual elements of the production in relation to Verdi's opera:

"Verdi improved on history by making jealousy over an unconsummated love-affair the motive for the assassination of King Gustav. Originally, Verdi had to move the action to Boston, however, where it doesn't make very much sense, even given the historical power of Puritan morality.

"Most of Northern Italy—before its unification—was occupied and ruled by the Austrian Empire. The Austrian censor surely feared that operas about killing kings might have given some spectators dangerous ideas. [Rimsky-Korsakov had similar problems with The Golden Cock.]

"Both Jones and McDonald are fascinated with the dance—which the king also loved. So one of the visual motifs is a dance-pattern painted on the great open pages of the book-stage. In King Gustav's time, new dances from Paris or London were sent all over Europe in this printed form.

"Because the reckless king refuses to listen to advice or warnings about his conduct or personal safety—given in almost every scene by all those close to him—the production becomes a virtual Dance of Death, or Totentanz.

"This is not only strongly underscored by the huge skeleton and the dance-patterns, but also by the haunting scene with Ulrika, the fortune-teller.

"Two things are standard in every Bregenz lake-stage production: fireworks and a ship or boat arriving on the water between the audience and the stage. The fireworks accent the festivities of the ball.

"The boat in Jones and McDonald's production is something else again. Jones staged Titanic on Broadway, so he knows about doomed ships.

"From the stage-right side of the great open book comes an immense black coffin, floating on the water. When it reaches front and center, it opens and there is Ulrika, making prophecies to various members of the Court. Including Amelia and the King.

"This unusual ship—with no visible captain—is constructed to hold up to forty people, but high water and choppy waves can make it an uneasy ride for chorus-members. You could get seasick just looking at it.

"When the team first saw the lake-stage, as Jones recalls, they realized that the performers would look like Lilliputians in Gulliver's Travels. That meant that small gestures or movements would visually be lost. But the solution was not just to make everything larger.

"Instead, they sought striking images which would convey something of the psychological forces at work in the libretto and score. The skeleton is one of these, as is the book—whose pages are headed with the king's name and dates.

"Another is an immense silver crown, with six points, which rises out of the book-floor at upstage right. When it is sunk in the stage, it seems only a ring on the surface.

"Rising hydraulically and made of polished chrome steel, it suggests not only the power of kingship, but also the inaccessibility of the king behind its protecting walls. Confronted by scores of petitioners, the king can escape from them over its margins or descend to them by means of a portable staircase.

"Rather than set the opera in its historical time, the late 18th century, Jones and McDonald have—primarily through costuming—transported it to the early 20th century. This time-frame is also emphasized when Amalia is driven home from her midnight herb-gathering in an elegant electrified Bugatti, which rises from beneath the book-floor upstage left.

"The stage-floor can hold up to 130 performers in a group, but more if they are scattered out. Sections of its pages downstage serve as steps, and its top and bottom binding margins are also playable.

"A "book-flap" rises from the downstage pages, so Ankarström can confront his—as he wrongly believes—adulterous wife at home. They have the longest table, not only in Sweden, but probably in the world. It rises along the entire front of the stage. It is in fact 32.50 meters long!

"The only other item of decor Chez Ankarström is an elliptical frame on the wall containing a crowned king's head—which could have been borrowed directly from a Max Beckmann painting. It also indicates the depth of the Count's admiration of and friendship with the king who betrays his trust.

"The standing pages of the great book conceal loudspeakers and also provide backdrop, wind-protection, and acoustic enhancement. Its summit is playable in the center, when the king's adoring page, Oskar, climbs up to aim a spotlight on the action.

"The skeleton—which rises 24+ meters from its pelvis at the water-line—can be climbed inside by lighting "techies" and on the outside, away from the audience, by stage-hands using the ribs.

"The right side of its skull, clearly seen only on one side of the amphitheatre, slides open to provide a major spotlight placement. The skeleton also conceals loudspeakers. Its core is a steel armature, covered with weatherproof modeling material."

I can hardly wait to see what Jones & McDonald will do for and with La Bohème next summer!

But opera-lovers may not want to find out what happened to Count Ankarström after he killed the King. He was flayed and tortured and exhibited in Sweden's major towns, finally expiring when he was "drawn-and-quartered."

This popular form of Public Entertainment and Crime Control was even more ghastly than the Inquisition's Burnings-at-the-Stake, for which the Pope recently apologized.

"Drawing" meant pulling out all the innards of the still-living victim to public exposure. "Quartering" required a division of the body into four parts. This was frequently facilitated by harnessing four strong horses to the arms and legs of the culprit—and then whipping them towards the four points of the compass.

Talk about "coddling" criminals today! Our European ancestors didn't know the meaning of the word "Rehabilitation." Or Forgiveness…

Also on the Bregenz Program—Beyond Opening-Week—

In the spacious new quarters of the Festival's Workroom Theatre—which also expand the offstage areas of the Main Stage—Astor Piazolla's María de Buenos Aires was premiered, under the musical direction of Gidon Kremer.This "tango-operita" featured Julia Zenko as Maria, with Facundo Ramirez and Mario Filgueira completing the cast.

In addition to various concerts—notably of the Vienna Symphony, the Deutsches Theater of Berlin brought its productions of Schiller's Don Carlos and John Millington Synge's Playboy of the Western World.

There were also a number of avant-garde art shows, so Bregenz is on the cutting-edge of culture not only in opera and theatre.

Cost-Cutting & Budget-Balancing—The Arts as Victim!

The future of the Bregenz Festival in now in doubt. Not that it will be shut down after more than half-a-century of successful productions—no one wants that!The danger is that most of its new and imaginative theatre and music programs will have to be curtailed or abandoned. Even as they were drawing new, younger audiences—the Audience of the Future!

This is because the Austrian government, back east, beyond the Alps, in Vienna, has begun a series of stringent budget-cuts. Unfortunately—and as usual in America as well—the Arts are in the first-line of areas for economizing.

But Austria is very different from America. It has always been understood in this small but historic nation that the arts, especially the performing-arts, need to be subsidized to maintain a high standard of achievement. Crowd-pleasing entertainments and sports can pay for themselves, but the High Arts are expensive to preserve and produce.

But they also have to be made available at popular prices—with tickets everyone can afford. Entrance to Austria's great museums and galleries—as well as to its great theatres, such as the Vienna State Opera and the Burg-Theater—must be kept reasonable. In order to provide a wide-ranging, readily available cultural resources to enrich the lives of every Austrian. Including the current bogey-man, Jörg Haider.

The popularity of the Bregenz Festival is not in question. This is its 54th season on the shores of the Bodensee. Its indoor and outdoor performances sell out regularly.

Its outdoor seating—beginning with less than a thousand plank-bench seats—over the years has been extended to the limit: 7,000 amphitheatre seats, all with excellent views. Even with subsidies from the Austrian, State, and local governments, 70% of the costs have to be covered by box-office sales.

At Austria's more famous and much more state-favored summer Salzburg Festival, lavish production expenditures are the rule. As are ticket-prices as high as $400 per seat at opera-stagings.

This is not the way of Bregenz, where ingenuity and economy rule backstage, with first-class results on stage. And yet Bregenz is to be punished for its success, with greatly reduced subsidies.

The Bregenz Festival—though it occurs only in July and August, about a month in all—is a major money-maker for the city and the region of Vorarlberg. It provides employment for a quarter of the local citizenry, in fact.

And the trickle-down effect of tourist expenditures in hotels, restaurants, shops, and other local cultural ambiances such as museums, galleries, and concerts is tremendous.

Despite this, Austrian federal funding is to be curtailed. Even in America, local, state, and federal government have invested in developing areas for tourism. These initiatives are not only designed to give such locales an economic "shot in the arm," but also to enrich the cultural lives of both locals and visitors.

In Austria, not only Bregenz and Salzburg, but also Graz, Linz, and other major and minor cities and towns have been immensely helped by state subsidies for festivals and similar events.

The current fever in Vienna of budget-cutting—retirement ages will be adjusted upward as well—will surely do harm to some areas of Austrian life which have long been a magnet for tourists from abroad. As well as curtail the cultural birth-right of many Austrians. It may even cost some of them their jobs!

The Timeliness of Of Mice and Men

It's especially interesting, therefore, that the second opera chosen for Bregenz's Season 2001 is Carlisle Floyd's Of Mice and Men, based on the novel by Nobel Prize-Winner John Steinbeck. It is to be performed indoors on the Festspielhaus stage.This tragic tale of little people with small hopes is set in the midst of America's Great Depression of the 1930s. After the Stock-Market Crash of 1929, millions of Americans were out of work.

In Of Mice and Men, George and Lenny are migrant ranch-workers, following the crops, or working on this farm or that, and then moving on. They have no home, no family—except for each other.

In the mid-1030s, there were thousands and thousands of migrant-workers, hoboes, and drifters like Steinbeck's duo, "on the road," looking for a day's work, a night's sleep-over in the barn or garage.

California was over-run by hordes of migrants from Oklahoma and Arkansas' "Dust Bowls," where they had seen their farms eroded by weather and blown away by tempestuous winds.

They were somewhat like today's westward migrants from Eastern Europe into, yes, Austria and Germany.

If you substitute "Ossies" for "Okies," the relevance of Floyd's heart-rending opera and Steinbeck's powerful novel should surely strike home for next summer's Bregenz audiences. Most of whom are prosperous West or Central Europeans.

Of Mice and Men may be the right work for the Bregenz stage at just the right moment!

Steinbeck's Social Relevance Beyond the Realms of Art:

In the American West, these "Okies" and "Arkies"—many being from drought-stricken Oklahoma and Arkansas—were definitely not welcome. But still they came, in broken-down cars and trucks, on freight-trains, even on foot. John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath powerfully recalls this in the struggles of the Joad Family.There was no place for them elsewhere in the United States. John Steinbeck had a compassion for these unfortunate Americans—which was certainly not shared by most of his fellow Californians. Especially in the Salinas Valley, where he grew up.

The "Okies" and "Arkies" had lost everything they cherished—as well as their means of survival. Californians, many of whom had come West only a few decades before the new migrants, were not eager to share lands or livelihoods.

As a "Native Son of the Golden West," for I was born in Sacramento, I experienced all this as a child, but from a divided point of view: "They don't belong here. They'll take all our jobs away." Versus: "They are people just like us. They need a helping hand, to get a new start in life!"

Had it not been for the social-welfare programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal," some Americans would never have recovered. Nor would millions of acres of American farmlands!

The New Deal injected millions and millions of federal government funds into agriculture, industry, environment, education, health, housing, transport, and, yes, culture.

Post Offices and schools all over America were decorated with historic murals of local events, painted by starving WPA artists. The protagonists of La Bohème should have been living in Chicago, or Nevada City, in 1935, instead of Paris a century before!

The Federal Theatre Project was ground-breaking in the development of Modern American Theatre. But it was soon shut down by the kind of politicians who are now at work in Vienna, "balancing the budget."

The cultural ignorance of those United States senators and congressmen who cut funds for the arts in the Depression Years before World War II is now legendary, but they knew very well—as they still do today, both in Washington and in Vienna—to play the Anti-Art Card.

In the Congressional hearings which culminated in the closure of the Federal Theatre Program, its brilliant director, Hallie Flanagan, was asked by one law-maker: "This [Christopher] Marlowe: Is he a Communist?" Orson Welles had just staged a memorable Dr. Faustus on Broadway for the Federal Theatre.

But then, Art and Communism were almost synonymous in these congressmen's minds.

Rituals and Pleas at Bregenz Opening Ceremonies—

It's customary at the Bregenz Festival to have a keynote address relating to the over-arching theme of the season's productions, or explicating a major work. So the prize-winning Moscow author-poet Olga Sedakova offered a scholarly exploration of the sub-texts of Der Goldene Hahn.Unfortunately, this came at the end of overlong remarks by various officials, so that it also seemed overlong. It was more interesting to read the text in German, than to listen to it, as read by Professor Sedakova in careful German phrases. Her attention to correct pronunciation prevented fluency and urgency.

She didn't seem very impressed herself with the significance of her opinions and judgments. She may well have been much more stimulating in the Opera Workshop which preceded the premieres. Here, opera-lovers, students, and teachers meet with critics, scholars, and artists to explore the works of the current season.

In recent seasons, the presence of Austria's President, Dr. Thomas Klestil, to officially open the Bregenz Festival, has been a regular feature. He is usually accompanied by a retinue of Viennese politicians and culture-mavens.

But this Millennial Summer was different. And not entirely to the liking of local citizens, who saw "their" festival being taken over by the Austrian State.

The Festival opening was in effect pre-empted by an Act of State, for which President Klestil had invited the President of the Swiss Republic, Adolf Ogi, and the sovereign of neighboring Liechtenstein, Prince Hans Adam II von und zu Lichtenstein. No German officials were on hand.

Federal protocol—and the Viennese equivalent of the Secret Service—constricted movement and limited attendance at some functions. Locals complained they couldn't even get a close look at the dignitaries.

I didn't get invited to the opening-night reception after Goldene Hahn, for instance. Although last summer I was invited to this event—and was even able to shake President Klestil's hand. I congratulated him on a provocative speech about the role of the arts, even though I suspected he was not its author.

This year he had much less to say about the arts, given Vienna's massive program of government cost-cutting.

The Festival's President, Günther Rhomberg, opened the event with a plea for preserving arts subsidies, especially for the Bregenz Festival. It otherwise faces stringent cuts in its innovative programming. And also possibly in its major productions, which are its bread-and-butter.

The two major Bregenz opera-stagings do not make money, or break-even. But they do recover three-quarters of costs and running-expenses at the box-office. This certainly cannot be said of the Salzburg and Vienna Festivals.

And certainly not of Covent Garden and the Metropolitan Opera, for that matter.

"Liberty" and "Freedom for the Artist" were called for, but not because Austria has an official censor for the arts. It does not. But cutting subsidies can achieve similar ends. Rhomberg was careful to note the needs of avant-garde artists, as well as of the festival itself.

A form of response was forcefully offered by Vienna's new Kunststaatssekretär, Franz Morak. This is apparently a new government position, one formerly covered by the Minister for Culture & Education.

Once art & artists are divorced from budgets for youth education and lifelong learning—which in Austria before always seemed to include culture—it may be much easier to slash arts-subsidies.

I was told that Morak is a former actor, but beyond that, I know nothing of him or his goals. You might well think that anyone who has worked in the arts—especially as a performing artist—would know well what the arts subsidy needs are, and why they are required.

Unless, of course, they are disappointed artists who gave it all up for politics, like Ronald Reagan.

But—as has been all too worrying for some Americans and Western Europeans—there have been some alarming populist changes in attitudes among the Austrian electorate.

In Austria, worried workers and farmers—the Little People, to whom rabble-rousers always first appeal—are understandably apprehensive about the inflow of Eastern Europeans. And of the economic changes which membership in the European Union will require.

Some of these fears have been played on by Jörg Haider, a sleek modern smoothie, with the political moxie of Louisiana's legendary "Kingfish," Huey Long. His admiration for another dubious Austrian politician, the late Adolf Hitler, has made him a real bogey-man in American headlines, as a result.

Liberal and conservative Austrian politicians don't yet seem to have effectively addressed the concerns which Haider raises. Cutting arts-subsides may be an effort to placate "Das Volk," who have always preferred sports-stadiums and beers to cultural events.

Unfortunately, I didn't get a text of Morak's address [in German] to study, for I don't listen in German as fast as he talks. But, at one point, I thought I heard him say that the People should to be the ones to support the arts.

Did he mean that they should pay for the arts directly, rather than through tax-monies administered by the government? I hope I misunderstood him.

If not, there goes not only the Bregenz Festival, but also the Vienna State Opera! [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home |

listings |

reviews |

cue-to-cue |

welcome |

| museums |

recordings |

coupons |

publications |

classified |