Two Views of "Our Class"

at BAM

|

“Our Class” a Gripping Exploration of Polish Anti-Semitism and Betrayal “Our Class.” “Our Class” by Tadeusz Slobodzianek, one of Poland’s most important playwrights, is a powerful and dramatic exploration of the impact of anti-Semitism and betrayal in a Polish village during and after World War II.

It is based on a true story, a pogrom 80 years ago when 1600 Jews in a Polish village were murdered by their classmates, neighbors and friends. The playbill audiences receive has matchsticks imprinted on it. Spanning the years 1939 and 2003, the play follows the intertwining lives of eight Jewish and Catholic characters as they struggle to survive the horrors of the Holocaust and then attempt to rebuild their lives in its aftermath. “Our Class” of course means Polish society.

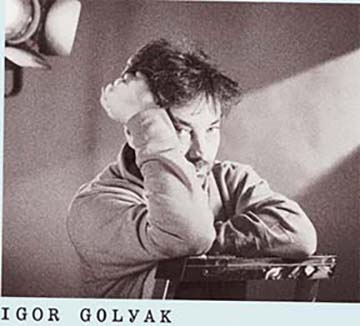

The innovative director is Igor Golyak, from Ukraine, trained by the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts and Moscow’s Schukin Theatre Institute (Vakhtangov Theater). With a mix of narrative and dialogue, the play relies on strong visual storytelling and a mixture of chillingly realistic scenes along with expressionistic elements to convey the trauma of the era.

It starts with the school children, Jews and Catholics, representing the Polish people.

The early scenes depicting the arrival of the Nazis and the beginning of the persecution of the Jews are harrowing, including the beating and murder of Jewish villagers. Some of the staging is surreal: a victim against a chalkboard outlined in white as the dead are outlined by police. In this, I talk about Jews and Poles, though the Jews are also Poles and the “Poles” are Catholics.

Central characters include Jakub Katz (a moving, powerful Stephen Ochsner), a Jewish villager accused of being part of the Nazi resistance; Vladek (Ilia Volok, seeming dumb but understanding the realities), who tries to save his Jewish love Rachelka (Alexandra Silber, brilliantly transformed through the years); Zygmunt (Elan Zafir, the smarmy villain), a Polish collaborator and informer; Zocha (Tess Goldwyn) a Polish woman who hides Menachem (Andrey Burkovskiy, performed with panache by a prominent Russian actor who deserves his acclaim), a Jewish survivor who joins the Polish secret police after the war. Their complex relationships and varying choices in response to the persecution around them form the core moral drama. Abram (Richard Topol) their teacher, leaves in time for America and is misled for years about how his family died in the village.

Events are visual and symbolic. Menachem has a new bike. The Catholics beat him and steal the bike. They return to their Christian prayers. Heniek (Will Manning, the guy you love to hate) carries a large wooden cross. Jakub asks, “Jesus is good with Wladek throwing rocks at my sister and splitting her head open? Vladek: “Someone had to shut her up. She was screaming like a banshee. (To Jakub Katz) I was aiming for you.”

In Golyak’s inventive staging, Jewish figures are depicted as faces on yellow balloons which are cut loose from moorings to float away to signify deaths. Zygmunt’s betrayal of fellow villagers to the Nazis is chilling, while Jakub’s steadfast refusal to confess to false accusations even under torture is moving and heroic. Vladek’s attempts to save Rachelka showcases the impossible choices faced by Jews trying to survive. Meanwhile Menachem’s turn to work for the Polish secret police after suffering torture himself highlights how trauma can twist moral reasoning.

The years are divided as “lessons.” Lesson 5, 1939, is Stalin. The Russian set up the Aurora move theater, which Menachem runs.

Rysiek (Jose Espinosa) a major Catholic betrayer and killer, yells, “Death to the Commie-Jew Conspiracy. Long live Poland!” Rysiek and other Poles start the White Eagle, resistance against the Russians, not the Germans. So, how do you feel when the Communist Russians abuse the Nazi Poles? Did they get what was coming to them? The playbill lists the characters with birth and death dates. Only three die in 41 or 42, others in the 70s, 80s and later. Two were Jews, one was Rysiek, who got what he deserved at the hands of another Pole. The play suggests that anti-Semitism and collaboration have poisoned this community for generations, ruining lives and souls, but mostly the Poles. As the characters age, their fates diverge but all are marked by the cruelties of the past. Heniek, now a priest, abuses altar boys. No surprise, always evil.

While unflinching in its depiction of moral corruption and violence, the play leaves room for redemption, as a few characters retain their humanity despite the horrors surrounding them. With its theatricality, expressionism and epic moral sweep, “Our

Class” brilliantly highlights questions of human nature, cruelty,

resistance, and moral choice. And the courage of Polish playwright

Tadeusz Slobodzianek to challenge the mythology of his country,

who would blame the massacre of Jews on the Russians. Visit Lucy’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com/ If Brecht Interpreted the Holocaust Our Class

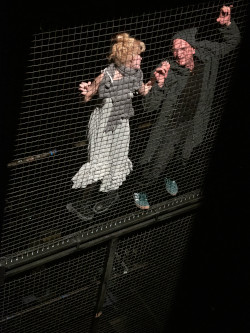

In many stories about the Holocaust there are definite good guys and bad guys. But in Tadeusz Slobodzianek’s Our Class there are neither. There are only cutthroats, survivors and victims, in this case ten classmates, half of them Jewish and half Catholic, whose lives we follow from just before until long after the war. The play is based on a true incident in which the Christian population of Jedwabne, a small Polish town, killed all their Jews, mostly by herding them into a barn and setting the barn on fire. This happened in 1941, so it was easy to blame the Germans. Only the survivors knew the truth. And they spent much of their lives hiding and justifying their actions. And because they stole the property of the murdered Jews, at the same time they benefitted from their ill-gotten gains. But what makes this telling of the story so different is the way Slobodzianek (as adapted by Norman Allen) and director Igor Golyak have embraced Brechtian techniques to tell it. As in Brecht’s Epic theatre, great pains are taken to remind the audience they are watching a theatrical production. It is staged as a reading, with the actors seated, script in hand. The backstage architecture (walls, ladders, lights) is a big part of the scenery, along with a chalkboard that doubles as a screen, and, thanks to several doors, a means of exits and entrances for the actors. The production also conflates form and content, symbols and reality, spectator and participant. Various characters speak while they are being recorded. An actor hands an audience member a camera. The production asks us to witness the unspeakable without sentimentalizing it. What Our Class does not provide Is answers. It’s easy to see how petty grievances become exaggerated in times of stress. Even in school Jew are isolated during mandatory religious services. The Poles blame the Jews for the sins of the Communists. But the violence, which includes rape, beatings and murder, happens so quickly and so excessively it’s hard to really understand where it comes from. Was it there all along, just waiting for the chance to escape? Equally hard to understand is the heartless behavior of the victims. Rachelka (Alexandra Silber) survives by converting to Christianity (she wears a large cross to confirm her new identity), marries a man she neither respects nor loves, and shows little concern for her suffering brethren. Menachem (Andrey Burkovskiy) deserts his wife and child; after the war he becomes a secret agent who resorts to much of the same kind of torture that made the Nazis notorious. And what about Abram (Richard Topel)? He emigrated to America, but he still communicates with those he left behind. What did he do to help or save them? Apparently, nothing. At the end of the play he names all his living relatives, of which there are many. Is this this a tribute to life, survival, procreation? Our Class makes considerable demands on both the cast and the audience. It is three hours long. The cast holds up its end magnificently. Those in the audience must be willing to be at various times puzzled, overwhelmed and horrified. They will not be bored.

|

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |