Lucy Komisar

|

“Here Lies Love” turns Philippines anti-Marcos struggle into an ahistorical musical "Here Lies Love." David Byrne’s pop musical docudrama professes to be the story of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos, their rise to power in the Philippines and the challenge to their dictatorship by Ninoy Aquino, who the Marcos government assassinated. It’s a smashing production. But a flawed history.

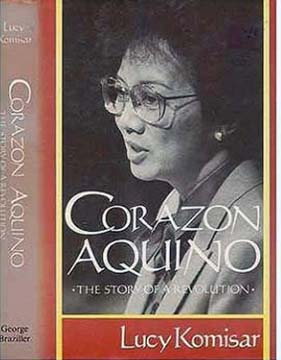

I know because I was there at a key time and wrote about the events in U.S. press stories and a book “Corazon Aquino: The Story of a Revolution.” I don’t know why Byrne wrote the distorted story, but unfortunately theatergoers will not remember even if they ever knew from U.S. media about the events described in 1986 and before. Because dictator Ferdinand Marcos was kept in power by the U.S. government to maintain an American military presence as he opposed a left-wing movement in favor of popular rights. And there was not much American press about that. Then he fled the country via a U.S. military helicopter that took him to Hawaii, with an estimated $10 billion in looted money. In 2001, daughter Irene Marcos Araneta was caught attempting to transfer $13.2B from the Lugano branch of the Union Bank of Switzerland to Deutsche Bank in Dusseldorf, Germany. The bank transfer was foiled.

First what is right about the production. It is technically riveting, visually stunning. It is easy to be pulled into the vortex. People downstairs on the theater floor shift in waves following the moving platforms. A high turning globe hangs from the ceiling flashing like a disco prop. The walls have bright neon designs and giant photos of the characters. The women wear the traditional puffed butterfly sleeves, named because they seem to be the wings of a butterfly on each shoulder. (Costumes are by Clint Ramos.) Think of being immersed in a music video. Actors and dancers move around downstage and alongside and up-level platforms. I was at the front mezzanine and suddenly Marcos (Jose Llana) appears on a platform inches in front. And then Imelda (Arielle Jacobs). And later a young Marcos lover (Julia Abueva). Singing, gyrating. The voices are generally good, though Imelda’s could be better, but there is nothing special about the repetitive singsong music and lyrics. Bryne is credited with “concept, music and lyrics,” music is by Fatboy Slim. And then what is wrong. It is flawed history. The whole first half, 45 minutes, is about Ferdinand and Imelda, their “love story.” What should be an introduction to the main political story becomes a “Sex and the City in Manila” tale. Flashback from 1985 to 1945, Imelda at 16 in Tacloban, an agricultural island an hour’s flight south of Manila. She’s a poor girl who wants to be rich, claiming, “Sometimes, I had no shoes.” Funny in the context of her presidential palace stash of 3,000 pairs of footware, which is never mentioned. She wins a local beauty pageant.

The play makes a big point about Ninoy Aquino (Conrad Ricamora), Marcos’ political nemesis, being Imelda’s boyfriend. The story not told is that the daughter of big landowner was married to a man whose uncle was Imelda’s father. And Ninoy was her nephew. The matchmaker put them together (Ninoy was 18, Imelda 21) and they dated for a while. That’s how connections among the ethnic Chinese in the Philippines worked. A teenager taking out a beauty queen for a time is not someone’s “boyfriend.” He later called Imelda beautiful but “antipatika,” in Tagalog, “displeasing, disagreeable, unfriendly.” Ninoy’s sisters also disapproved and connected him to Corazon Aquino, of another wealthy Chinese-Filipino family, whom he wed in 1954. That year, Imelda and Ferdinand also married, and Imelda declares that that Marcos taught her “how to do it…he taught me nightly.” It may be just scuttlebutt, but when I was in the Philippines in 1986, I was told that Imelda needed no teacher. Still, a New York doctor gives her yellow pills, amphetamines, and she reminds herself she is doing it “for love.” Something is already wrong.

In 1965, Marcos runs for president. A character sings, “Sometimes we need a strong man.” He makes promises to the poor, of course. But money flows in another direction, for example to an apartment on the Upper East Side of New York, a launching spot for Imelda’s visits to Studio 54. It takes a while for the story to get serious. About halfway through the 90-minute production, the play begins to notice the political situation. In 1969, Ninoy attacks Marcos for his policies and corruption. The play ignores the building popular movement growing in the country. It also doesn’t mention the essential support Marcos was getting from the U.S. government, which likes its Philippines military bases. Imelda was promoting the construction of a massive cultural center (which Ninoy called a pantheon for Imelda — not something the poverty-stricken people really needed), and later, in 1981, a famous accident leads to the deaths of 169 workers whose bodies are entombed in the cement. We see the pictures of the poor. But again, there’s no context, nothing about the building movement, nothing about the role of the U.S. which supported Marcos through the years. “Marcos” appears on the mezzanine ledge a foot from me with a very young tacky woman in a black bikini. This is Dovie Beams (Julia Abueva), a U.S. actress who flew to Manila to be in a film about Marcos’ war exploits and had an affair with him. She was 20 and he 60. At Beams’ departure, she held a press conference and ran sex tapes she had secretly recorded; the play uses them for lyrics. Across the way, an older Imelda, labeled “her inner voice” (Jasmine Forsberg in a spun gold dress), is shown distraught at the sight. “You play around with that woman. Didn’t you know I cared?”

In the midst of all the sex stories there have been massive protests – ignored by the script – and Marcos has responded brutally. Ninoy on a platform declares, “I am outraged at how the students were bludgeoned and truncheoned by the police last night. The students were protesting the graft and corruption rampant in this administration.” On the mezzanine ledge in front of me appears an exaggerated American figure in a rubber mask. It would have been Nixon. Marcos declares martial law in 1972. There will be, according to visuals, 3,200 killed, 35,000 tortured, 70,000 jailed.

There is a timeline in the program. It is ignored in the script. The infamous “Order 1081” charges Ninoy with bombings, and he is arrested in 1973 and kept in prison for seven years. Then, suddenly, events happen fast. Finally, in 1980 he is released. May 1980, Ninoy: “It’s my country that I’m leaving.” He goes into exile in Cambridge, Mass. And the next text August 1983 is Ninoy: “They have two guys stationed to knock me out at the airport.” We see the video of him assassinated on the tarmac. And Marcos flees on a U.S. helicopter in March 1986.

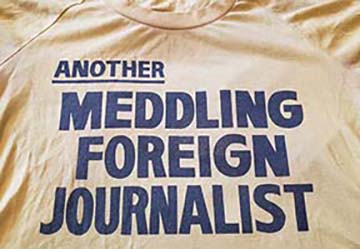

Wait a minute. Not so fast. The play has wiped out years of popular organizing all through the 70s and before and after Ninoy’s death in 1983 and demands for a free election. The role of his widow Corazon Aquino is not there, obliterated. That alone makes it a fake story. The play can’t ignore the culmination of the “People Power Revolution” and the Feb 22-25, 1986 mass mobilization of 2 million people along the major avenue known by the acronym EDSA. The DJ (Moses Villarama) says, “So many people, everybody is here. The girls from the office, the guys from the street.” Though he erases Cory’s role as the speaker at a mass rally, but those days are what most Americans know about the overthrow of Marcos. There were so many international reporters there that we had our own yellow t-shirts picking up Marcos’s attack: “Another meddling foreign journalist.”

The DJ tells of the choppers taking off, but there’s nothing that says it was the Americans who rescued their client Marcos, along with the billions in looted cash. Pity that such an inventive production is paired with such a flawed historical story.

Journalist Lucy Komisar reported on the Philippines in 1986 and is the author of the political biography, “Corazon Aquino: The Story of a Revolution,” published in 1987 by Braziller, New York, and 1988 by the National Bookstore, Manila, and Benziger Verlag, Zurich. She is also a theater critic and member of New York’s Drama Desk. Her book was reviewed in The NY Times and in The Christian Science Monitor, as copied to this CIA file. Visit Lucy’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com/ |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |