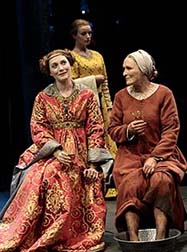

Two views of "Mother of the

Maid"

Lucy Komisar

Edward Rubin

|

Glen Close is a terrific actress. Too bad she is starring in such a bad play. She makes it worth watching, even if you cringe at Jane Anderson's hokey script that walks straight out of television, dumbing down events of the 15th century so viewers can connect as they do to their favorite sit-com. Anderson has done a lot of TV, and it we see the result.

Think of Joan of Arc, here Joanie (Grace Van Patten) calling her mother "Ma" and speaking with a slight New York twang. Or her mother, Isabelle (Close), dressing down a lady of the king's court and inviting the lady's daughters to visit her "s?hole" of a peasant's house where they will learn how to behave. Did you think this was a faithful take on what might have happened in those days? Other examples. Talking about Saint Catherine whose voices Joan, I mean Joanie, hears. "She's a lovely saint. She's got a halo." Mom says: "If you play your cards right, you could be an Abbess."

When Joan says God has a plan for her to lead an army and drive the English out of France, Mom retorts, "Oh, stop. Get off your high horse." Mom plans to visit the Dauphin's palace. Her son, who has accompanied Joan there, promises, "I'll show you a good time, ma." Joan arrives in her male doublet and trousers. Nicole, the Lady of the Court (fine understudy Kelley Curran) tells her the outfit is a hit, "some of the ladies have ordered doublets." Mom is miffed when told she can't see Joan till the young woman is finished praying. I liked Joan's descent in an ethereal white dress on stairs surrounded by banks of votive candles. Lovely Hollywood stuff. So, what do you talk about in the palace? Jacques (Dermot Crowley) her father, remarks that you can't heat a room with ceilings so high.

Joan, in armor, tells her family, "It's a big day. I'm glad you're here." The problem with this play is that it's a cartoon. The characters do not fit into that period. Jane Greenwood's costumes are of the 15th century, but the language is today's vernacular. I almost expected a character to say, "I was like?.." or end a sentence on the upswing. I assume director Matthew Penn played a role in creating the sit-com mood. If this were a "silent," his direction would have been fine. After the English capture Joan, her brother remarks, "She's a celebrity. She will be safe." I cringed. The family priest recommends they light votive candles. "Of course, I'll waive the fee." Close is terrific as the mother, at times calm, sorrowful, angry, distraught, determined, with great emotional power. Van Patten is a sweet ingénue, but it's hard to see in her the woman who inspired the French army. Crowley as Dad and Andrew Hovelson as the brother are fine for TV. I found Kelley Curran diverting as the Lady of the Court; she would fit perfectly on a ladies' daytime talk show. Clothes, kids' education, etc, and very generous in spirit, nothing like the selfish aristocrats we've learned about.

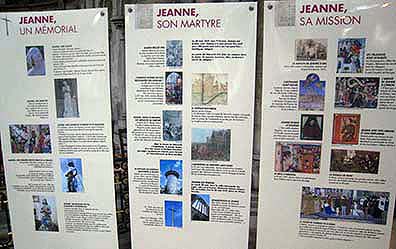

Well, we know how it turned out, in the play and life. Captured by French nobles allied with the English, she was put on trial by a pro-English bishop and burned at the stake May 1431 in Rouen. She was 19. Could the French king have saved her? The argument is that he didn't have the cash the British demanded as ransom. Only 25 years later, a papal court pronounced her innocent, declared her a martyr. She would be made a saint in 1920. As her dad comments, it was all politics. Called heresy at the time. A convenient target in the British-French Hundred Years Wars. Against an aggressive female, no less. (Today, her accusers would say she was an agent of the Russians!) If you visit Rouen Cathedral, you will see a poster on the facade inviting you to a Jeanne d'Arc internet site and, inside, an altar devoted to her life.

Visit Lucy's website http://thekomisarscoop.com

Written by Jane Anderson, directed by Matthew

Penn. People on trial, especially women that end up being executed make good theatre and film, as well as subjects of art. The two reigning queens whose lives still continue to resonate long after their deaths are Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), the last Queen of France, who literally lost her head, and Jeanne d’Arc (1412-1431) who went up in flames nearly seven centuries ago. Done in by politics, both were captured, jailed, put on trial, dragged through the streets and summarily executed, as a kind of entertainment before a boisterous crowd of unruly citizens. And ever since their demise each continue to be resuscitated, again and again, in both fictive and non-fictive modes, for the viewing, listening, and reading pleasure of those of us still alive.

The latest Joan of Arc re-creation, currently playing at the Public Theatre in New York City through December 23, is Jane Anderson’s play Mother of Maid, starring Glenn Close as Joan of Arc’s mother. I might add, before going any further that there are three major reasons which make this play well-worth seeing. Glenn Close! Glenn Close! And Glenn Close! Her rock-solid presence, strongly insistent, as is her style, dwarfs every cast member around her. Obviously she is the play’s calling card. This is Mother of the Maid’s second go around, as the play

had its world premiere at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts

in 2015. Since then Anderson restructured the play by eliminating

one character, and combining two others, thus allegedly simplifying

the play for future audiences. In the old version Joan’s mother

shares the narration with Saint Catherine, the very saint who told

Joan to drive out the English out of France and bring the Dauphin

to Reims for his coronation. In the newly renovated play, it is

Joan’s mother alone – an interesting conceit –

who gets to tell her daughter’s story from a mother’s

point of view.

The well-worn, well-known story of Joan of Arc, architecturally speaking, is usually presented, whether on stage, film, or in book, as a straight-on retelling in which we get to follow Joan’s battlefront triumphs, her capture and jailing, her trial, and her very end when she is burned at the stake. And all through these tellings it is Joan herself who appears front, center, and in our face. Not so in Anderson’s version. Here, her Joan of Arc (Grace Van Patten), though half of the play’s title and the main topic of everybody’s attention, from her mother Isabelle (Glenn Close), her father Jacques (Dermot Crowley), her brother Pierre (Andrew Hovelson) who follows Joan into battle, and all of the other minor characters in the play, come across, in all but her one prison scene, as background fodder, a major minor second fiddle if you will. While Mother of the Maid does skim the highlights of Joan’s

short life, rather perfunctorily – she goes up in smoke at

age 19 – the story as it unfolds here is shockingly shallow

in depth. In fact, the overly simple seven-scene play, which presents

all of the characters in an annoying folksy contemporary vein –

can you believe that the 15th Century Joan keeps calling her mother

Ma – is at best a Cliff Notes version of the Joan of Arc story.

It can also be viewed in its simplicity, as a historical children’s

fable. Unfortunately, here we only hear about the trial, and superficially at that. In fact, most of the action, including Joan’s private meetings with the Dauphine who was her mentor – and who among us would not want to be a fly on the wall – take place off stage. For the record, no person of the middle ages, male or female, has been the subject of more study than Joan of Arc. There is a wealth of historical material available. The main sources of information are the chronicles. Five original manuscripts of her condemnation trial surfaced in old archives during the 19th century. Historians also located the complete records of her rehabilitation trial, which contained sworn testimony from 115 witnesses, and the original French notes for the Latin condemnation trial transcript. A wealth of similarly kept historical documents exists for Antoinette also.

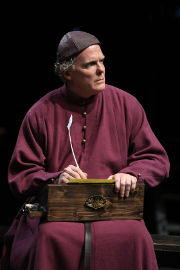

Although all of the secondary actors in Mother of the Maid, from Joan’s father Jacques (Dermot Crowley), her brother Pierre (Andrew Hovelson), and Daniel Pearce who plays three roles, that of Father Gilbert, Chamberlain, and a scribe, turn in performances, as accomplished as the script allows, it is Kate Jennings Grant’s Lady of the Court, the most naturally spontaneous written character in the play that I found most interesting. Though Grant’s role as a noblewoman is on the smaller side, and she appears in only two scenes, her character, the least rigid in the play is the only character that I wanted to see more of. Her skill in showing compassion, mother love, friendship, and true self-reflection, was mesmerizing in its honesty. Equally alluring, in view of the extreme seriousness of Joan’s plight and her parent’s incessant worrying about the safety of their daughter, is Grant’s light touch which adds a few dollops of levity of which the play offers little. Aiding and abetting each of Grant’s scenes was the magic

hands of scenic designer John Lee Beatty, and costume designer Jane

Greenwood, who took us from the drab brown and grey settings of

the Arc’s home in Domrémy, in northeastern France,

to the bright and colorful, ornately designed chamber in the Dauphin’s

castle. Though the play could have ended right then and there, another scene, the last, has each character informing us in monologue style, as to what happened to them after Joan’s death. The father’s tale, though he always suspected that harm would come to his daughter, was most heartbreaking. Sparing his wife the horror of watching Joan at the stake he sent Isabelle off to a chapel to the other end of the city so she would be spared the smell of the smoke. Wanting his daughter to know that he was proud of her, he stayed to the bitter end, “till every last trace of his girl was gone.” He didn’t leave until the soldiers scooped up her charred remains and threw them into the river. It must have taken its toll as Jacques died in the ox cart on the way home. “His heart seized up. It was grief,” Isabelle informs us. As far as Pierre, something of a wastrel, he too showed up for the burning as well, but he spent most of “his time in a tavern drinking himself sick. He paid his bar bill with a hank of his sister’s hair that he kept in a pouch along with the tip of the arrow he once pulled from her flesh. He went back to the army, drank some more, and prayed to God that he’d get hit.” Of course, the indomitable Close gets the last word. “Isabelle Arc was never going to get over it. Never. But she wasn’t going to fade away in the dark of an empty house. She got herself a proper horse and wagon and she travelled. She learned herself how to read. She went to Rome and she met with the pope and told that man in the hat her daughter was no bloody heretic. She faced a tribunal of clergy, three rows of them in robes black as crows, all of them just waiting for the poor dim peasant woman to fall to pieces. But she didn’t. Isabelle Arc stared those bastards down and she cleared her Joanie’s name.” Just before the stage goes black and the play comes to a close, a still grieving Isabelle, looking over our heads, out at the horizon in front of her, asks us if we hear those birds. “How do they keep up it up all day? It must be for pure enjoyment. And look at all these wild flowers -- how do such delicate things manage to push their way up out of the dirt. And all those silly bees digging in to those blossoms, sucking up the nectar, not giving up -- oh the greedy, greedy things. And smell that air. So full of the sweetness of grass and bud and life. And the sky. Such a clear, clean blue. This is what made my daughter’s heart so large. She didn’t need to conjure up some saint. This, all this...this is pure goodness.” Waiting a few beats she ends the play with the saddest, tear triggering words of the evening, “I had a daughter once.”

|

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |