Lucy Komisar

Beckett’s

“All That Fall” is tough poetic

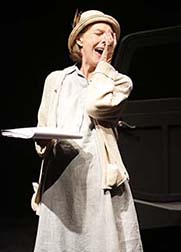

“All That Fall.” Think of the fall as the prelude to the end of life, the difficult bumbling interval preceding finality and death. It’s a time that presents more misery than joy in Samuel Beckett’s “All That Fall,” a 1957 BBC radio play being staged with exquisite tenderness by Trevor Nunn at 59E59 Theaters. But there’s also a quirky and bizarre sense that makes you marvel for a moment at peoples’ ability to hang on and assert themselves even as their physical beings are failing. “Fall” here is the verb. This production is anchored in brilliant performances by Eileen Atkins and Michael Gambon, among Britain’s best actors, as the frail married couple who retain just enough energy to flail and thrash at each other. Old life is passing, new life is budding, or is it nipped in the bud? Maddy Rooney (Atkins), a lady in her 70s in a white up-brimmed hat and cardigan, is making a tedious journey to the railroad station to meet her blind husband who is returning from his office. The exertion makes you think this is a cross-country trip. Atkins face is withered by desperation, her eyes peering but only half-seeing. She rues her lugubrious life which she passes in a ruinous old house. She is childless. “Love is all I asked,” she laments. Old Mr. Tyler (Frank Grimes), comes upon her on his bike. When he offers her his arm to help her to the station, she accuses him of molesting her. After he rides off, she frets about her corset and cries, “Mr. Tyler, come back and unlace me behind the hedge.”

Finally, Mr. Slocom (Trevor Cooper) drives up in his car and offers her a lift. She can’t climb into the seat without Slocom exercising a strong push to her derrière. Atkins makes that scene more tragic than funny. She wants to be wasting painlessly away. “I estrange them all,” she declares. Now she’s angry that the train on which her husband, the white haired Dan (Michael Gambon), is arriving from his office is late. She is picking him up rather than letting him take a taxi, because it is his birthday. She demands to know at the station why the train hasn’t arrived. She is told that there was “a hitch.” But then Mr. Rooney arrives. Gambon plays him as a fellow so tough and crotchety that you forget that he is blind and not in possession of all his physical senses. He tells her she is shaking like a blancmange. They take halting steps, he with a cane. They laugh and joke about death. Sometimes he explodes in fury at his impotence. She is just as tough.

They are annoyed by some children who in the past have pelted them with mud. He asks, “Did you ever wish to kill a child? Nip some young doom in the bud.” He recalls having restrained himself from attacking young Jerry (Liam Thrift) who helps him from the train. Though he insistently refuses to tell his wife why the train was late, Jerry informs them that “the hitch” is that a child fell out of the train carriage and under its wheels. Beckett presents a mystery about how that happened. One wonders if Dan did it? Is this a parable about the struggle between life and death? At one point, Maddy tells Dan the text of Sunday’s sermon. “The Lord upholdeth all that fall and raiseth up all those that be bowed down.” They laugh. Nobody is raised up here; life is misery. Nunn has staged the play as if it were in the radio studio, with hanging microphones and actors holding scripts. But the characters fire your visual imagination as much as they must have the visions of listeners to the radio play.

|

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |