Lucy Komisar

| THREE

VIEWS OF "THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE" by

Lucy Komisar Brecht’s

“The Caucasian Chalk Circle” is “The Caucasian Chalk Circle.”

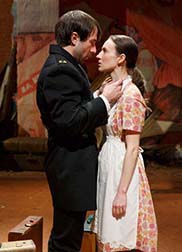

Bertolt Brecht’s 1944 play with music – almost a chamber opera – is a satiric parody about selflessness and greed. As the narrator puts it, “Terrible is the temptation to do good.” Classic Stage director Brian Kulick helms a strong production laced with Brecht’s irony, colored by caricatures and driven by strong performances. He has edited the text, but he remains true to the author’s conception. Kulick starts the play at the turn of the last century and ends with the collapse of Soviet communism. The production begins as a play within a play, actors struggling against continual blackouts that leave them in darkness. It’s an apt metaphor. This is a time of upheaval in early 1900s Georgia. Revolutionary paintings are on the wall. There’s a statue of Lenin. The governor has been killed and the grand duke overthrown in a coup by the prince. Grusha (Elizabeth A. Davis), the young kitchen maid at the governor’s house, is the good soul to whom everything terrible happens. The governor’s wife (the incomparable Mary Testa), abandons her baby as she organizes her wardrobe for the flight to safety.

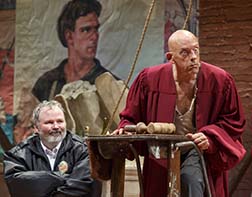

Grusha rescues the infant and then flees, as the Ironshirts — soldiers meant to resemble Nazi storm troopers — pursue the child who is perceived as a threatening heir. She leaves in spite of the danger that she will not again find her soldier sweetheart. Davis encompasses the girl’s innocence, but she is too mild for the role. She is overpowered by others in the cast. The scowling village clerk Azdak (a very idiosyncratic, dominating Christopher Lloyd) shelters a fugitive whose white hands show him a landowner. Lloyd is the ballast of the production. Azdal later realizes the “beggar” is the duke. However, he is charged with stealing the prince’s rabbit. He declares, “I am despicable, treacherous, branded! Tell them, flatfoot, how I insisted on being put in chains and brought to the capital. Because I sheltered the Grand Duke, the Grand Swindler, by mistake.” But when he accuses himself, everyone laughs. Power shifts, and Azdak is put in a position of authority. It’s a new age, maybe. Azdak, who in some respects speaks for Brecht, declares, “Everything is being investigated, brought into the open. In which case a man prefers to give himself up. Why? Because he won’t escape the mob.” He says, “Judgment must always be passed with complete solemnity—because it’s such rot.”

“Suppose a Judge throws a woman into the clink for having stolen a loaf of bread for her child. And he isn’t wearing his robes. Or he’s scratching himself while passing sentence so that more than a third of his body is exposed—in which case he’d have to scratch his thigh—then the sentence he passes is a disgrace and the law is violated.” The play is also a satire and critique of the military. It could take place today. The prince wants to make his nephew the judge, but requires the Ironshirts’ support, so Azdak plays the duke in a mock trial. The prince’s nephew declares to Azdak, ”You’re being accused, not of declaring war, which every ruler has to do once in a while, but of conducting it badly.” THE NEPHEW It’s not your business to command me. So you claim the Princes forced you to declare war. Then how can you claim they made a mess of it? AZDAK Didn’t send enough troops. Embezzled funds. During attack found drunk in whorehouse. THE NEPHEW Are you making the outrageous claim that the Princes of this country did not fight? AZDAK No. Princes fought. Fought for war contracts….Princes have won their war. Got themselves paid 3,863,000 piastres for horses not delivered…. 8,240,000 piastres for food supplies not produced…. And therefore victors. War lost only for Grusinia, which is not present in this court.” The Ironshirts like Azdak and make him the judge. And the bribes continue. It’s so much a part of the job of a judge that he seems destined to grab for the cash. He has to adjudicate an absurd dispute over the theft of a cow and a ham. Of course, injustice ensues. That doesn’t last long. The Ironshirts decide that Azdak is an enemy of the state. Meanwhile, Gursha carries the child across rickety bridges and into snowy villages where she desperately seeks shelter, meeting mean welcomes even from relatives. At the end, Brecht presents the parable of the chalk circle which is just a variant of the Judgment of Solomon. Grusha and the governor’s wife, who both want the boy, are ordered by the judge to each take an arm and pull the child (an entrancing puppet) over opposite sides of a chalk circle. Brecht’s play is a political cartoon, and director Kulick draws it expertly. The shift to the fall of the Soviet Union occurs so seamlessly, that you can’t tell it except for the Coca Cola sign. The actors are a fine ensemble, especially Testa as the governor’s loud-mouthed wife. This Classic Stage revival shows again why the Company is so important to New York.

Visit Lucy Komisar’s website: The Komisar Scoop “The

Caucasian Chalk Circle” Teaches Valuable Lessons The Caucasian Chalk Circle As a playwright, director and Marxist, Bertolt Brecht sought a theater that had social and political goals. Unlike the purveyors of melodrama, he didn’t want to engage the audience’s emotions but rather their reason. Nor did he want his audiences to enter into the illusion of the play. Brecht believed it was most important for those watching his plays to be detached from what they were seeing. In this way they would be encouraged to think about their own life and the world around them, and perhaps be inspired to effect change. Toward that end, Brecht employed various techniques to break theater’s traditional fourth wall. He flooded the stage in bright light, and he had actors play multiple parts, move props and sometimes address the audience. He created interpolated songs, projections and signs to emphasize important points. Brecht’s plays were written and acted in a way that relied more on reporting and description than the naturalistic techniques of Stanislavski. And, as in Greek theater, a chorus commented on the action, which is why this form of theater became known as “epic.” And what was the result? Brecht created some of the most moving drama in the Western canon. This beautiful failure is spectacularly illustrated in Classic Stage Company’s new production of “The Caucasian Chalk Circle.” Written in 1944, while Brecht was living in the United Stage, “The Caucasian Chalk Circle” is a parable of biblical proportions (indeed it borrows from the Old Testament). In order to settle a land dispute dispute that emerges between two communes after World War II, the story is told as a play-within-a-play to illuminate the problem. The Singer and his troupe of musicians tell the story of a peasant girl who finds an abandoned child, does everything in her power to preserve him and finally has to assert her claim when the natural mother arrives In CSC’s version, directed by Brian Kulick, with new music by Tony Award-winner Duncan Sheikthe, the story seems to take place at the point when capitalism is about to take over (represented by a toppled statue of Lenin). A cast of seven plays all the roles with Elizabeth A. Davis as the peasant; Christopher Lloyd as both the Singer and the astute (and drunken) judge, Azduk, who finally determines who shall have the baby (represented by a beguiling puppet); and. Mary Testa as the child’s natural mother (and the Mother-in-Law and Old Lady). Ms. Testa, who has a perviously scheduled conflict, will be replaced by Lea DeLaria for the final two weeks of the show. “The Caucasian Chalk Circle” is both entertaining and disturbing. Sometimes the actors bring member of the audience onstage, make humorous asides or ask the audience to sing along with them. At other times they display raw emotions that can break your heart. Davis is particularly engaging as the devoted adoptive mother. While Testa is appropriately ridiculous and foolish as the hypocritical biological mother. But it is Lloyd whose performance best captures Brecht’s vision of justice in a chaotic world. Lloyd, whose career spans stage and screen, Broadway and off-Broadway, is equally at home in Shakespeare and Star Trek. He brings all this experience to the absurd and larger-than-life character of Azduk. If we never quite believe in the character (as Brecht would have it), we certainly believe in the very humane values of fairness, love and compassion that he represents. “The Caucasian Chalk Circle” constantly moves in treacherous waters, but the cast is always sure footed as it guides the play relentlessly toward it’s very satisfying and moving conclusion. Liars,

Killers, Cheaters, and Self-Servers with a Happy Ending "The Caucasian Chalk Circle”

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) and I are in total agreement

that mankind, not us but them, as I like to say to avoid argument,

is populated by liars, killers, cheats, and self-serving louts. One

only need to look around, listen to the daily news, or for that matter

attend any one of Brecht’s more popular plays to meet these

people. Serving up a dish of rotten folk, with one or two good ones

thrown in for good measure, is the Classic Stage Theatre’s production

of Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle nicely directed by CSC’s

artistic director Brian Kulick.The “play within a play”

opens with a scene-setting prologue, updated to include recent events

such as Chernobyl. The prologue’s ultimate purpose is to let

us know up front – and know we do, down to our very bones –

that no matter when or where or what is happening on stage, the play

is essentially about us and the times we live in. In the background,

further indicating time, place, and circumstance, we see a partially

destroyed statue of Lenin. A change of government is in the air. The

first words to fall on our ears come from the camp mouth of a flamboyantly

made-up Mary Testa. She is quickly joined by Alex Hurt, Deb Radloff,

Jason Babinsky, and Tom Riis Farrell, a chorus of actors, all of who

deliver their scene-setting lines in Brecht’s typically exaggerated

anti-realist style. Mary: “Moscow is nothing but ministries, ministries,

ministries. Ministry of this, ministry of that.” Alex: “I heard they are now selling sausage contaminated with pesticides, hormones and radiation from Chernobyl.” Deb: “Our revolution was a disaster. Our revolution -- all it did was make it possible for the most evil people to have the most power.” Jason: “It's hopeless. And this will go on forever and ever. It's always like this in Russia.” Tom: “What is one Russian? -- A fool, And two Russians? -- A fight, And three Russians? -- A Vodka line.” The “frame” play takes place somewhere in the Soviet Union around the end of the Second World War. It opens with a dispute between two communes, a fruit growing commune and goat farming commune, over who is to manage an area of farmland after the Nazis have retreated from the village. To shed light on the dispute, a parable play is organized by one of the communes with all of the actors, except for Elizabeth A. Davis, a 2012 Tony nominee for Once, playing multiple roles. The through line of this play is simple—a peasant girl Grusha (sweetly played by Davis) rescues a baby that the fleeing Governor’s wife (Mary Testa) inadvertently leaves behind after her husband is killed during a coup. Thus begins Grusha’s flight as she attempts to keep the baby from the new ruler, the Fat Prince (Tom Riss Farrell), and his Ironshirts Gestapo-esque guards, who want to kill it. Along the way, as Grusha crisscrosses the landscape, all the time being chased by the Fat Prince and his gang, she falls in love with a handsome young soldier (Alex Hurt), crosses a range of treacherous mountains to live with her brother and his wife, eventually ending up, in one of the play’s more funny scenes, marrying a dying man (Jason Babinsky). To usher the audience along this journey and punctuate each plight as it unfolds – a little hand-holding is definitely needed – Brecht employs a narrator called The Singer. His role, frenetically played by Christopher Lloyd – he chews up the scenery in both acts – is to impart the inner thoughts of the play’s various characters, as well as to signal the changes in scene and time. As act one ends, The Singer announces: “The Ironshirts took the child away, the precious child. The unhappy girl followed them to the city, the dangerous place. The real mother demanded the child back. The foster mother faced her child. Who will try the case, on whom will the child be bestowed? Who will be the Judge? A good one, a bad one?” As it turns out, act two, seemingly another play, yet set within the same war setting, centers primarily on Christopher Lloyd, whose vocal and physical calisthenics continues to turn the stage into his private fiefdom, not unlike Mark Rylance’s 2011 Tony winning performance in the play Jerusalem which had him rolling around the stage. Here, Lloyd goes from playing The Singer, to becoming Azdak the village clerk cum bribe-taking judge. His outrageous behavior which supplies much of the play’s levity, favors the poor, the oppressed and good-hearted bandits. The play ends with Grusha and the Governor’s wife, each claiming the right to keep the baby, standing before the Azdak in court. His judicial decisions, zany, purposeful, and happily accidental, change everybody’s world. |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |