Lucy Komisar

|

|

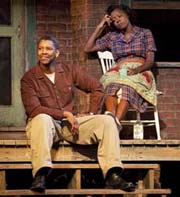

| Denzel Washington and Viola Davis. Photo by Joan Marcus. |

Denzel Washington as Tony Maxson and Viola Davis as his wife Rose are tragic figures who encompass desperate desires to get ahead and heartbreaking experiences of failure. They shine in director Kenny Leon's production that at once tugs at your heart and makes you furious. Leon directed Wilson's "Gem of the Ocean" and "Radio Golf" on Broadway and knows very well how to mine circumstances in the playwright's work that bring forth both sympathy and dismay.

The setting is Wilson's Pittsburgh, this time 1957, at a shabby brick house with a back porch and paved over yard, a tall maple planted in the hard dirt and concrete as if to emphasize that this space that ought to be for grass and shrubs is sterile. Close next door is a similar red brick two-story home. The set is by Santo Loquasto.

|

| Stephen McKinley Henderson and Denzel Washington. Photo by Joan Marcus. |

Troy, who is 53 and working on a garbage truck, vents his anger

at racism to his co-worker and friend, Jim Bono (Stephen McKinley

Henderson, who has become a necessary featured actor in Wilson's

works.) Troy complains that the whites get to drive the trucks

while blacks haul the garbage cans. He refers in a dreamy way

to the time when he played minor league baseball. Even that

didn't work out. He grumbles that white men won't let him get

anywhere. Washington gives a brilliant performance as a man

eaten away by anger and resentment.

His isn't the only family tragedy. Gabriel (Mykelti Williamson), his brother, has a plate in his head from a war wound and now hallucinates. He gets some welfare, but not the care he deserves. (Of course, the Veterans Administration is famous for the bad treatment given veterans of all races.) Gabe says he's gone to heaven and seen St Peter. He imagines he chases Hell hounds, and he carries a trumpet for Judgment Day. Is that an ironic reference to the Biblical Gabriel and his horn? (The real, fine trumpet music is composed by jazz musician Branford Marsalis.)

|

| Chris Chalk and Denzel Washington. Photo by Joan Marcus. |

But Wilson is not writing agitprop. This story is complex, and there's blame to go around. On the down side, Troy's past includes some dicey events in the years before he played baseball. And his stony emotional failure repeats the lack of love his felt from his father. In a grabbing moment of the story, he repeats that failure with his own son, Cory (played with subtly controlled emotion by Chris Chalk), who has dreams of accepting a football scholarship that will get him to college. "How come you never liked me?" Cory asks.

Troy's inability to understand the meaning of

love leads to the betrayal of his wife Rose, played with tenderness

and strength by Viola Davis. Yet, Wilson knows how to pull survival

out of the family tragedies, overcoming the "dysfunctions"

that sociologists are still studying. That may account for the

enthusiasm of black audiences who see heroism through the pain.

| lobby | search

| home | cue-to-cue |

discounts | welcome | film

| dance | reviews

|

| museums |

NYTW mail | recordings |

coupons | publications |

classified |