Lucy Komisar"The Orphans' Home Cycle" is a gripping, elegant saga of a Texas family "The Orphans' Home

Cycle"

|

|

| "The Orphans' Home Cycle, "Hallie Foote. Photo Gregory Costanzo. |

In a grand work divided into three performances, each of three hour-long plays, beginning 1902 and with smart photographic backdrops, Foote has brilliantly etched the personal and economic details of Horace Robideaux' life, beginning when he was 12 and his father, a locally prominent lawyer, died from drink. The work proceeds to his struggles as a youth rejected by his mother, a young man facing economic reversals and difficulties with women, and finally to the challenges of marriage and family life.

Foote has said the plays are based on family stories and indeed the series is inspired by the life of his father, whose history mirrors that of Horace. The cast, headed by Bill Heck as the grown-up Robideaux, is superb. Hallie Foote, Horton's daughter, does a dazzling job, starting with Grandma Robideaux and ending as Horace's mother-in-law, her southern accent authentically dripping East Texas on the Gulf.

The central tragedy of life is etched when Horace's mother (Virginia Kull) marries his step-father (Bryce Pinkham) who prefers his sister, the spoiled Lily Dale (Emily Robinson). They deprive the child Horace of school and family, leaving him in Harrison (modeled on Foote's Wharton, TX) when they move to Houston. He is dealt a loveless, hard-scrabble life.

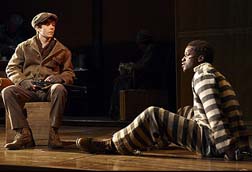

|

| Henry Hodges (as young Horace) and Gilbert Owuor. Photo Gregory Costanzo. |

The episode that stunned me the most takes place in the early days when Horace (Henry Hodges), destitute at 14,works in a plantation dry-goods store and witnesses the horror experienced by black chain gang prisoners, convicts a relative obtained from the state to replace slaves that once worked there. James De Marse is chilling as the nasty, drunken plantation owner Soll Gautier who stiffs Horace for his labor. There continues a theme that moves through all the plays – the hard-drinking of the friends and family that people the saga.

|

| Jenny Dare Paulin and Bill Hecht. Photo Gregory Costanzo. |

Another theme is their small-mindedness and meanness, exemplified by Davenport (Devon Abner, 7 years after the first episode) and the selfishness of Horace's sister Lily Dale (then Jenny Dare Paulin).

The dreariness is cut by Horace's young manhood and courtship, though this very naïve young man has bad judgment in his choice of friends and an unfortunate lot in some relatives (gamblers and drinkers) topped off by ill luck with women, at least at the start. Heck, a protagonist in most of the play, carries off his role expertly, letting the audience feel his pain and admire his solidity and strong character.

A pastime even more popular than drinking in Foote's small town Texas was gossiping. Neighbors and relatives end up, we hear, as "dope fiends," in mental institutions, or unmarried and pregnant. Perhaps that's behind the insistence of the dour, harsh, judgmental Henry Vaughn (DeMarse), that his daughters not have boyfriends. That of course leads to defiance.

|

| Bill Hecht and Maggy Lacey. Photo Gregory Costanzo. |

Horace will finally get a good, warm wife, Elizabeth Vaughn (Maggie Lacey). But their largely insular world suffers the intrusion of the Great War and a deadly flu epidemic.

The funniest play in the lot is "Cousins," a parody of the extensive extended families in which cousins are all called "cousin," as a family honorific, except, as one points out, 'We don't call a lot of our cousins "cousin," and another queries, as if the listener were somehow forgetful, "Don't you know everybody you're kin to?" They drink and chat about who is cousin to whom. One remarks, "A family is a remarkable thing. You belong and then you don't."

Foote paints the strengths and weaknesses, the sensitivity and cruelty of his characters, with the admirable Horace a good man who stands out in a world peopled by the crude and the unfeeling. Parts of the story reminded me of an updated Charles Dickens.

The brown earth tones of the clothes (David C. Woolard) and settings (by Jeff Cowie and David M. Barber) emphasize the down-to-earth nitty-gritty of the world we are observing.

This is an extraordinary multi-faceted drama which deserves recognition in America's theater canon. The production is a tribute to Foote, who died last year at 92.

| lobby | search

| home | cue-to-cue |

discounts | welcome | film

| dance | reviews

|

| museums |

NYTW mail | recordings |

coupons | publications |

classified |