|

New Orleans

Carnivals

Book review: "New Orleans Carnival Krewes: The History, Spirit

& Secrets of Mardi Gras"

By Rosary O'Neill; foreword by Kim Marie Vaz. 238 pp. Illustrated.

Charleston: The History Press. $19.99 paper. ISBN 978.1.62619.154.9.

Reviewed by Jack Anderson

|

|

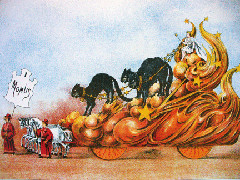

Rex

poster for 1936 Mardi Gras. |

People like to parade. People like to party. People like to don extravagant

or even outlandish outfits that have nothing to do with the sober

stuff they might choose as workaday attire. People simply like to

show off. And certain communities are celebrated for allowing citizens

and visitors to do just that. One city famous, even notorious, for

revelry is New Orleans, with its balls, parades, and carnivals. Mardi

Gras ("Fat Tuesday") may literally be only a single day:

the day preceding Ash Wednesday, which opens the penitential season

of Lent. But in New Orleans the Mardi Gras spirit seizes the city

weeks before that and never really leaves it.

Rosary O'Neill, a native New Orleanian from an old-line Carnival

family and a professor emeritus of theater at Loyola University who

is now a New York resident, has traced the history and analyzed the

significance of New Orleans Carnival krewes in this spirited and richly

illustrated account. She uses the term s "old-line" and

"krewe" before she fully defines them, but definitions are

soon provided and, in any case, readers can easily guess the meaning

s of those words: "krewes" are Carnival organizations (that

curious spelling, O'Neill says, is an old English form of "crew")

and the old-line krewes are those that have survived for generations,

many of them with mythological, or at least fancy, names. New Orleans

makes much of tradition. Even though, or possibly because, "the

majority of the city's first settlers were refugees, commoners and

ex-convicts" (p. 22), Orleanians love to indulge in aristocratic

fantasies. There's certainly nothing ordinary about Carnival. O'Neill

finds parallels to New Orleans Carnivals in Renaissance and Baroque

masques, and she describes present-day Carnivals with such zest that

parts of the concluding sections of her book sound as if they could

come from a tourist brochure.

So, then, why not just relax and "Laissez les bons temps rouler"?

|

| Early

20th century postcard showing riders and float of a day parade

on Canal Street, 1909. |

Not so fast. Carnivals may be sunny in spirit. But they are not entirely

sweetness and light. As O'Neill clearly and carefully points out,

New Orleans Carnival societies (and the old-line ones go back to the

Nineteenth Century) are inextricably tied to the city's social, economic,

and racial politics. O'Neill loves Carnivals, but has no illusions

about them.

"New Orleans carnival organizations," she says (p. 16),

"are exclusive, secretive, private and predominantly male associations

that dramatize the city's social structure through parades and balls."

The most well-established ones are also predominantly Christian. Although

the first king of the venerable Rex krewe back in 1872 was Jewish,

O'Neill notes that "this phenomenon has not reoccurred"

(p. 75). Stringent, and discriminatory, membership restrictions began

to loosen up after the 1930's (and, again, post-Hurricane Katrina).

In 1941, the Krewe of Venus was the first organization to allow women

to ride on its parade floats. African American krewes began flourishing

in the early Twentieth Century, and in 1991the City Council ordered

all Carnival organizations to declare that they did not discriminate.

Yet, as O'Neill notes (p. 92), although New Orleans is now predominantly

black in population, its Carnival organizations remain predominantly

white. The old-line societies constitute a self-perpetuating autocracy

and membership in them provides "entry into other closed clubs,

business contacts and exposure to advantageous marriage partners."

(p. 103).

|

|

Mardi

Gras Parade, 2011 |

All this may be changing, especially as the city recovers from the

devastation of Katrina. New krewes are being organized and, of course,

one does not have to belong to a krewe to participate in Carnival,

for New Orleans streets during merrymaking times are thronged with

"promiscuous maskers." Carnival has even come to serve as

a symbol of civic resilience, of the city's ability to rise above

and defy adversity. No wonder O'Neill, for all her awareness of its

problems, still loves Carnival and can write about it enthusiastically.

Yes, indeed, "let the good times roll."

|

|

Postcard

panorama of "Rex" parade on Canal Street, New Orleans

Mardi Gras, 1904. |

New Orleans Carnival Krewes

Farce

New Orleans Carnival Krewes

By Rosary O'Neill

New Orleans means the French Quarter, the Garden District, corrupt

politicians, good food, good music, and most of all, Mardi Gras. In

her new book, New Orleans Carnival Krewes, Rosary O'Neill, a native

New Orleanian living in New York, concentrates on Mardi Gras, but

inevitably includes all those other fascinating subjects as well.

The history, spirit and secrets of the Mardi Gras are inextricably

allied with the history and culture of New Orleans. Anyone who wants

to study the first will undoubtedly become immersed in the latter.

O'Neill's research includes both published and unpublished articles

as well as interviews with carnival leaders, many of whom prefer to

remain anonymous. She has divided her book into eighteen chapters,

beginning with the birth of carnival Krewes and ending with the carnival

today.

The story begins in Europe, where Roman Catholic countries have celebrated

carnival before Lent for centuries. It then goes to New Orleans, a

stronghold of Creole (a mixture of Spanish and French) culture, where

the tradition of society balls and and secret parade societies coalesced

into the first carnival society. And it ends with the carnival today,

a more democratic, more commercialized version of the original.

New Orleans Carnival Krewes is illustrated with pictures of carnival

floats, parades and participants. Pictures scattered throughout the

book go back to antebellum celebrations. Others show the the indomitable

spirit of post-Katrina New Orleans. They are all in black and white

but do not fail to illustrate the glorious sense of style and display

which means so much to New Orleanians.

O'Neill does not shy away from the darker side of carnival, from

its associations with racism to its crude excesses. She makes quite

clear how carnival has historically underlined the vast differences

race and economic status make in how the event is celebrated.

But she also shows how the carnival reflects many of the changes

brought about by the more progressive movements of the 20th century.

Most of all, O'Neill reveals how Mardi Gras epitomizes the best in

New Orleans: the sense of family, the love of life that comes with

food and drink and dress, and the special magic that are the soul

of this great city.

New Orleans Carnival Krewes, by Rosary O'Neill, is published by The

History Press www.historypress.net. http://www.history/

|