| "The

Lehman Trilogy"

Absolute theatre magic!

|

| Photo by Stephanie

Berger. |

From

22 March to 20 April, 2019.

Mon. – Thurs. at 7 PM; Fri. – Sat. at 7:30 PM; Sat.

at 1 PM.

Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue, NYC.

Tickets: $45-$1256; online https://www.viagogo.com/Theater-Tickets/Theater/The-Lehman-Trilogy-Tickets/E-3401868.

"The Lehman Trilogy" by Stefano Massini, adapted by Ben

Power. Directed by Sam Mendes.

Reviewed by Glenda Frank.

"The Lehman Trilogy," in a limited run at

the New York Armory, is almost four hours long and features three

actors in a glasslike cage. What can you expect from this? Absolute

theatre magic! The production, directed by Sam Mendes ("American

Beauty"), is mesmerizing.

The trilogy tells the story of the three generations of the family

that built the financial behemoth, which folded in 2008. The giant

transparent cubicle (Es Devlin, set design) revolves to provide

various interiors. The pictorial backdrop (Luke Halls, video design)

sets the scenes, changing for place and time, even for major events

like the cotton fire that devastated Alabama in the 1850s. And the

reflecting floor (Jon Clark, lighting) makes the whole seem –

at times -- to be floating in a high rise far above the city.

The three actors who play a multitude of genders and ages, tap

our imaginations in ways that are more than impressive. When Simon

Beal (named the greatest stage actor of his generation), a stout,

bearded man of a certain age, transforms into a slender young woman

being courted by one of the original Lehman brothers, we witness

the courtship. The limited number of actors and sets keeps our minds

focused on (fascinated by!) the story of the family. Lines repeat,

like an incantation.

Characterization is quick and vivid. We are reminded at key moments

that Henry Lehman, the oldest Lehman brother, is the Head. He makes

the decision. Emanuel (Ben Miles, Tony nomination for "Wolf

Hall") is the Shoulder; he carries them out. And Mendel (Adam

Godly, Tony and Drama Desk awards nominations for "Anything

Goes"), the youngest, is the Potato, smooth, a peace zone between

the two brothers – who they discover has some brilliant ideas

of his own. The men first sell to Straw Hats (Alabama locals) but

as business grows, they sell to the Big Cigars and later strike

up a lucrative bargain with Perfect Hands, a wealthy factory owner

in the North.

|

| Photo by Stephanie Berger. |

The actors are clad in modern dress and somber colors. While the

several rooms in the cube contain tables and chairs, seating arrangments

change by rearranging storage boxes. (The boxes are also a reminder

of the root of the family's success, the store in Alabama.) Move

the boxes and you have the interior of a coach. Move them again,

and the father, on the taller stack, sits with his son and the son

plays with his invisible beard. The concept is not new but on this

scale – a trilogy in the Armory – it is daring and exciting.

The audience is tapped as an important aspect of this creative process.

The trilogy consists of "Three Brothers," "Fathers

& Sons," and "The Immortal" (about the company).

"Three Brothers" is a paean to the immigrant experience

and the American dream. Its format is story theatre: much direct

address to the audience. It begins with a dream of "the magic

music box called America" -- the dream of Henry Lehman, son

of a cattle merchant in Rimpar, Bavaria. The 45-day passage is transformative.

The teetotalling boy becomes an expert drinker, who can distinguish

not just various liquors but the quality of his drink. The boy who

never gambled arrives adept at dice and cards. And so, open to change,

he embraces the multiplicity of New York, but moves to Montgomery,

Alabama, to open his shop. He hand paints his own shop sign. The

sign is continually repainted by the brothers as the business grows.

"A can of paint on the sidewalk" is one of several refrains,

which evokes family history with a light, almost self-deprecating

comic touch.

Once his two brothers arrive, the action speeds up. The fraternal

battles are lively as the Lehmans change direction and struggle

with a steep learning curve. Idea begets idea. Henry ("who

is always right") decides to add seed and farm tools to the

inventory. Emanuel balks, so the brothers canvass the farmers to

learn if there is a need. They begin to accept raw cotton as payment,

but selling the cotton yields a small profit. (Yes, during slavery.

They were not social pioneers.) After a visit to a New York cotton

exchange, they learn how to make the transport of cotton profitable

and they create a new profession – middlemen.

|

| Photo by Stephanie Berger. |

They are businessmen and their courtships are based on that paradigm.

Emanuel marries a Southern belle -- for love. He is so infatuated

that he makes bookkeeping errors. Wed to the business, Mayer, the

youngest brother, decides which alliance would make him happy and

presents himself. Unlike his older brother, he does not court her,

not in the traditional sense. He appears at her door and proposes

24 times and finalizes the wedding date with her father. Phillip,

Emanuel's son, draws up a list of eligible women, assesses their

strengths, then proposes.

The trilogy is filled with comical and quirky touches, all intrinsic

to the characters. Herbert Lehman, who is upset because his sisters

are not treated as equal to his brothers, is discovered to be a

poor fit for the business. He becomes the 45 Governor of New York

(1933 -1942) and a US Senator (1949 – 1957). Philip Lehman,

who runs the company as it transitions from a commodities house

to a house of issue, feels in constant competition with his more

famous brother. A tightrope walker on Wall Street becomes a metaphor

for the high-risk trading world. Words (like "shares")

have replaced objects (like tons of cotton) in their business dealings.

The story of Noah and the ark becomes a cautionary tale for running

the company, even as they market the self-serving slogan that buying

is winning.

The play ends where it began, with the three brothers, the small

shop in Montgomery, and the dream. Toward the end, the trilogy takes

on a moral tone. The family has lost its values. In the end, the

company is controlled by strangers. Henry, the eldest brother, closed

the dry-goods shop on Shabbat (Saturday) but opened it on Sunday.

When Henry died, the brothers observed the Jewish traditions of

mourning; they sat shiva for seven days and tore their suits. In

the next generation, they mourned a death for three days. And in

the third generation, three minutes. The first and second generations

married for life. Bobbie Lehman, the third generation, was divorced

twice. The immigrant saga becomes the contemporary American story.

"The Lehman Trilogy" covers 150 years of western capitalism.

It was written by Stefano Massini and first performed in Paris is

2013. The 2015 staging by Luca Ronconi in Milan captured international

attention and has enjoyed multiple stagings throughout Europe. The

English version has been adapted by Ben Power, Deputy Artistic Director

of the National Theatre, where this version of the plays premiered.

"The Lehman Trilogy" a fascinating

family tale misses financial corruption

|

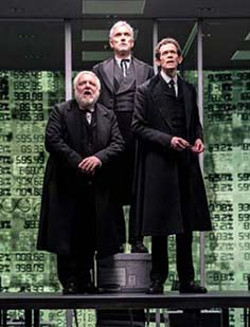

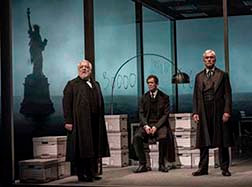

| L-R: Simon Russell Beale as Henry

Lehman, Ben Miles as Emanuel Lehman, Adam Godley as Mayer Lehman.

Photo by Stephanie Berger. |

Written

by Stefano Massini, adapted by Ben Power, directed by Sam Mendes.

Produced by the National Theatre and Neal Street Productions, in

collaboration with Park Avenue Armory.

(212) 933-5812; http://armoryonpark.org/programs_events/detail/lehman.

Opened March 22 , closes April 20, 2019.

Running time 3:20.

$45 rush tickets on day of performance at the Box Office beginning

12pm (two per person).

Reviewed

by Lucy Komisar.

Truth and a bit of fantasy. A quite extraordinary play of how generations

of an immigrant family create a major financial institution that

starts as a southern cotton farming supply shop and ends as a multinational

bank whose crash helps bring on the Great Recession of 2008.

It attempts to tell the story of western capitalism through the

fortunes of this very industrious and far-sighted family. Unfortunately,

the choice to present this as largely a family story misses the

financial politics that would demonstrate that this is not just

about three immigrant brothers from Germany and their progeny, but

about the systemic corruption of the US and international financial

system.

The play by the British Ben Power is based on a work by the Italian

Stefano Massini and staged by the accomplished British director

Sam Mendes. So, perhaps they are not grounded in US financial history.

And they particularly could not establish links between the corruption-fueled

Depression and the collapse of the Lehman bank in 2008.

As a piece of theater, this is brilliant, fascinating. The brothers

and their sons down the line (where are the women?) are played powerfully

by Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, and Ben Miles. Arriving in

Alabama in the mid-1840s, they go from running a farming supplies

shop to moving cotton to the north. Then they establish a bank.

We know that slavery was the economic foundation of the cotton south,

and then of the financial system built on it. It was a building

block of the American economy. The Lehmans in fact owned slaves.

But this is not about slavery, which doesn’t appear to raise

any moral problems among the clan.

The next big flaw is the treatment of the 1929 crash, when we see

the suicides of ten or more stock traders, each described in detail,

but not a word about the Pecora Report, that famous investigation

of the time which told how the men who ran Wall Street were corrupt

manipulators who brought the system down.

The scenes occur in a brilliantly clever set of a rotating glass

square by Es Devlin, with video of changing backdrops by Luke Halls.

But I’m an investigative journalist as well as a theater critic,

and for me the story counts more than the visuals.

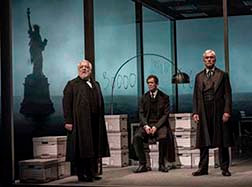

|

| L-R: Simon Russell Beale, Adam

Godley, and Ben Miles, immigrants, an office view of the Statue

of Liberty. Photo by Stephanie Berger. |

Henry Lehman, born 1822, had been dreaming of America.

He makes the passage in 1844 and goes to Alabama. His brothers Emanuel

(Ben Miles) and Mayer (Adam Godley) arrive a few years later. They

move from dry goods to what is needed for growing cotton. There’s

a terrific drama of plantations on fire, the need for their services

to rebuild — seeds, tools, to be paid for in raw cotton the

Lehmans will resell up north.

The glass square turns as time goes on. Through the south, they

are the middlemen, brokers. Brother Emanuel goes to New York where

the real money works. A point is made of their Jewishness, but that

mostly deals with business – they can't get into some, they

have an advantage in others.

Henry dies of yellow fever. The family continues, expands its business.

We learn how Lehman Brothers Cotton moves to financing railroads

and becomes Lehman Brothers Bank when the government of Alabama

subsidies it. It’s now known as crony capitalism or socialism

for the rich. The bank will move to Wall Street as industrialization

puts down strong roots and will become an investment bank.

|

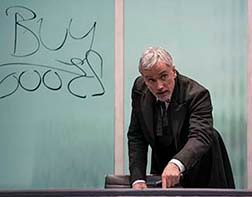

| Ben Miles as a trader. Photo by

Stephanie Berger. |

The glass office is gorgeous, now with a brown leather couch, corporate

conference table, and file boxes that bespeak Germanic organization.

The surrounding buildings get taller. Philip who takes over in 1887

wants to finance a Panama Canal. Wants to turn Lehman Bank into

Lehman Finance. Ah, the financialization of the global banking system.

A son Robert who comes to the bank in 1925 goes to Yale and turns

to Wall Street.

There are comic scenes with the wives (Adam Godley is good as the

cartoonish women), but there are no real women’s roles. The

younger men have modern business school voices, but it’s hard

to tell them apart. And then the 1929 crash. People demand their

money. Stock brokers and investors jump out of windows. Investment

funds are at zero. Banks are closing. What if everyone stops believing?

The really admirable Lehman is Mayer’s son Herbert, who leaves

the firm. He becomes New York’s governor 1933-47 and US Senator

1949-57. He says, "Grabbing and greed can go on for just so

long, but the breaking point is bound to come sometime."

|

Simon Russell Beale as one of the

last of the Lehmans running the bank,. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

|

But the Lehmans and the firm don’t stop believing,

or find it useful to believe, and the author doesn’t mention

the Pecora investigation that exposes internal market corruption.

Time moves to the near present. A Lehman, Robert, will run the bank

for the last time, till 1969.

Pete Peterson, who had been Richard Nixon’s commerce secretary,

takes the top job. Then he is bought out by American Express, and

Dick Fuld takes charge. And comes the 2008 crash. Hank Paulson,

the Treasury head who had come from Goldman Sachs, bails out Goldman

but refuses Lehman. It’s called insider corruption.

Adapter Ben Power writes that through the family and "the hubristic

tragedy of 2008" we can see "where we are and how we got

there."

The personal stories and the fine acting link events together, but

not well enough to inform anyone in the audience who already doesn’t

know "how we got there": the story of the corrupt financialization

and government cronyism benefiting the favored banks and squashing

the others. Not to mention the government’s failure to act

to protect 7 million Americans who lose their homes as the result

of banks’ corrupt mortgage operations, so brazen that they

include "losing" documents that show people paid off their

mortgages and going to court to foreclose on their homes. Or the

millions who lose jobs.

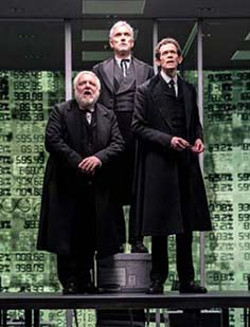

|

L-R:Adam Godley, Simon Russell

Beale, and Ben Miles, Photo by Stephanie Berger.

|

The play focuses on the building of a financial empire. The cast is

superb, and Mendes is a very fine director. The missing story is

how that empire and others like it crash the world financial system,

destroy lives, while in the case of Lehman Brothers Finance, it

is destroyed itself. The real dénouement is how Lehman’s

competitors with better political connections use their control

of big governments to bail themselves out and continue as financial

predators.

Visit Lucy’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com/

|