THE OLD WOMAN

by Glenda Frank

| "The Old Woman," adapted by Darryl Pinckney from a novella by Russian surrealist Daniil Kharms. Direction, set, and lighting by Robert Wilson with music by Hal Willner. Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 30 Lafayette St., NYC. June 22 at 7 PM; June 24-8 at 7:30; June 28 at 2; June 29 at 3. Tickets $25 -125. Tickets and information at 718-636-4100 or http://www.bam.org/theater.

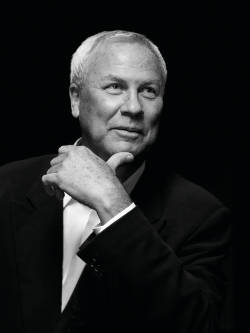

Robert Wilson's "The Old Woman," playing only eight performances in the Gilman Opera House at BAM, is beautiful. Certainly visually striking, but more. It has a transformative energy generated by the conflation of fine aesthetic sensibilities with emotional insights into the human condition. This is not to say it's stuffy. It is always entertaining and very, very funny, filled with vaudeville routines, odd stories, and dreamlike juxtapositions. The stage drama is a construct of verbal, visual and aural elements: a catchy abstract score by Hal Willner, snippets from popular songs, and the actors' voices in a range from screams to gravely baritone. Despite the several creative hands, "The Old Woman" feels like a gestalt rather than a collaboration. Clad in identical black suits with pants ending above the ankle, sporting eccentric cowlicks, and wearing white face, the two protagonists are played by Willem Dafoe (an original member of the Wooster Group with over 80 films to his credit) and Mikhail Baryshnikov (former artistic director of ABT with multiple awards for theatre). The actors create multiple relationships throughout the 12 short scenes (plus epilogue). They are at times aggressive, new lovers hesitantly sharing a glass of vodka, dance partners, buffoons, observers, friends. Often they echo the same lines in Russian (with super titles) and English. The pace is livelier than most Wilson creations but still demands that we recalibrate from a New York minute to the metronome of the piece. (One of the actors holds up a large clock which states one time yet he reads it as another.) All Wilson compositions are dream sequences with iconic figures, postures and gestures. "The Old Woman" is more accessible although, as with dreams, there are limits to literal interpretation.

The work opens with an evocative poem by author Daniil Kharms, which is repeated variously throughout: This is how hunger begins: Both Wilson and Darryl Pinckney, who adapted Daniil Kharms' novella, took great liberties. The production can be read as a comical disquisition on aging, madness, existential angst or totalitarian persecution. Several times an actor will open his very red mouth and scream, pause, then scream again. The screams are interesting rather than affecting, presentational rather than profound. And yet -- they remain human screams -- which opens emotional possibilities. Or none. The audience, too, is the author of this experience.

The set is a wonder of asymmetrical angles and size distortions against a color-altering backdrop. A day-glow white door frame is Alice-in-Wonderland size while a white bed bends in the center at an obtuse angle, and a huge white chair seems to swallow the performer. The actors freeze from time in angular postures, like postmodern dancers. The eponymous old woman is part of an anecdote about a curious woman who leaned too far out of the window and fell. As in a hall of mirrors, behind her was another old woman who, too, fell from the window out of curiosity. And behind her -- well, you get it. A line from Kharms' novella, too, recurs: "And what would you say to us buying some vodka now and going to my place? I live very near here." Romance, death, absurdity, pain. Kharms himself died in 1942 at the age of 37, in a Nazi blockade of St. Petersburg. He had been arrested for writing experimental prose and even after becoming a writer of children's books was harassed by the new soviet government. Knowing the plotline of "The Old Woman" is perhaps more hindrance than help in absorbing the stage presence. A writer finds the body of an old woman in his room. Afraid of police accusations, he stuffs the corpse into a suitcase and takes it on a train, where he loses it. Wilson himself claims there is no single narrative. He begins first with the lighting design, then movement and, lastly, text and audio, freely constructing and deconstructing. He envisioned the two characters as complementary aspects of Kharms, the fictional protagonist, but it is clear that they are also equally viable (and more engaging) as separate people. One of my favorite moments was when Baryshnikov, noticing Defoe's deep grunts and extreme head tilt, attempts to help his friend stand straight. With each turn and twist, Defoe's voice changes as he tries to communicate. The scene could be emblematic for the multiple personalities (i.e. voices) we all possess, but what struck me more was the difficulty (and mastery) of the non-linear script -- most of which demands split second accuracy -- and the talent of these performers. In the program notes, Baryshnikov observed: "One minute you're a silent movie actor, the next a vaudevillian, the next a Noh theater performer. This in addition to Bob's precise staging and lighting." Even at one hundred minutes without an intermission, "The Old

Woman" feels just right. No. Better than just right. |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |