|

“The Transfiguration of Benjamin Banneker”

|

| Benajmin Banneker puppet. Photo by Chris Ignacio. |

LaMama E.T.C. (Ellen Stewart Theatre)

66 East 4th Street, NYC

Jan. 23-Feb. 2, 2020

Th.-Sat. at 7:00 p.m.; Sun. at 3:00

Box office 212-352-3101, www.lamama.org

Reviewed by Dorothy Chansky January 24, 2020

These days, “arts and sciences” sounds like about as

likely a pairing as, oh, maybe snowshoes and spaghetti, what with

STEM and humanities understood by so many as antitheses with no

hope of appeal across the aisle.

The eighteenth-century Benjamin Banneker felt and acted otherwise,

and in Theodora Skipitares’s inventive theatrical investigation

of this extraordinary man’s life, science inspires poetry

and sculpture, while painting is the realm of farmers and astronauts.

|

| Banneker Puppet. Photo by Theo Cote. |

Banneker, the son and grandson of African slaves, lived his life

as a free man on a farm in Maryland, from his birth in 1731 until

his death in 1806. He taught himself astronomy; he borrowed a pocket

watch and, after taking it apart, used it as a model to build himself

a clock that ran for fifty years without losing a second. He wrote

to Thomas Jefferson about racial inequity, decorously noting that

all humans belong to the same family and holding TJ’s feet

to the fire about that pesky “we hold these truths to be self-evident”

bit. He wrote several almanacs, using spherical trigonometry; he

predicted (accurately) four eclipses; he was a surveyor of the new

city of Washington, D.C.

His house and books were burned the day of his funeral. So much

for accomplishment and model citizenry on the wrong side of the

color line.

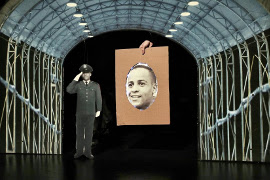

|

| Banneker head with Soul Tigers in finale. Photo

by Theo Cote. |

As in many of Skipitares’s earlier works, a particular person

or event or category of experience provides the nodal point from

which this master puppet-maker and thinker makes cross-cultural,

transhistorical connections. Previous projects include pieces about

the history of medicine (“Under the Knife,” 1994) and

food as the stuff of myth, profit, and power-brokering (“Empires

and Appetites,” 1989). Her 2014 “Chairs” took

on Ionesco’s play by creating individual chairs “hosting”

twenty-nine (important, if not yet fully famous) guests, contra

the source text’s silent pieces of furniture to sit on which

no one ever arrived.

|

| Reginald L. Barnes, the narrator who plays

Banneker and Edward Dwight, Jr. Photo by Kristina Loggia. |

Banneker’s fascination with the galaxy and the racism he

encountered provide a jumping-off place for Skipitares to make connections

with twentieth-century astronauts who have also gone on record about

the wonder—and the racism—they experience in relation

to space. Early in “Transfiguration” we hear Banneker

wax eloquent about his fascination with the universe: “The

moon is within me and so is the sun. Suppose we really are made

from the stars.” The Banneker puppet—in the Bunraku

family—has moveable arms and legs, but his torso is a hollow,

heart-shaped, metal frame with a bright light representing his actual

heart. Puppeteers who manipulate Banneker remain mostly in the shadows,

but occasionally they dance along with his utterances, a deft in/out

relationship between effigy and human as co-builders of what we

perceive as a character. (Puppetry Direction is by Jane Catherine

Shaw.)

|

| Miniature toy theater, scene of

story of would-be astronaut Edward Dwight, Jr. Photo by Theo

Cote. |

Fast forward a couple of centuries. Consider the case of African

American space program trainee Edward Dwight, an 85-year-old sculptor

and astronaut manqué (yes, he’s still alive) who makes

a major appearance in “Transfiguration.” A Kansas native

interested in art, he walked away from an art school scholarship

when his father persuaded him to study engineering. His success

yielded an invitation from the Kennedy administration to join the

astronauts’ training program. Dwight was awed by the peacefulness

he experienced flying an F-104 Starfighter. Seeing our planet without

territorial borders and encased in what he describes as a magical

blue layer changed his life. He tells us that Russian astronauts

are nearly all also artists—the experience is that inspiring.

But NASA needed popular backing if it was to be profitable, and

Dwight realized that it is heroes who inspire followers. If heroic

work could be performed by women or blacks, however, it ceased to

be heroic to the American man in the street. Borman and Armstrong,

yes. Dwight? Not so much.

Borman also makes an appearance during a toy theatre sequence featuring

two-dimensional cut-out figures within a tiny proscenium ringed

by lights. He succinctly disses legendary instructor Chuck Yaeger

for the latter’s orders to the astronauts in training to shun

Dwight: “Do not socialize with him, do not drink with him,

do not invite him over to your house, and in six months he'll be

gone."

|

Banneker puppet. Photo

by Theo Cote. |

There is more to this show than skillful and imaginative puppetry

and zingy narrative. Students from the (NYC public high school)

Benjamin Banneker Academy’s marching band, the Soul Tigers,

provide drumming intervals, one of which works as a counterpoint

to Banneker’s correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, with explosive

snare riffs (Banneker) squaring off against less fireworksy bass

sequences (Jefferson). Dancers wielding and wearing strings and

rings of lights bring stars to life. (They are Banneker students

Adeoba Awosika, AnnJeane Cato, Isabel Elliott, Halle Gillett, Janee

Jeanbaptiste, and Kimori Zinnerman. Choreography is by by Edisa

Weeks in collaboration with Jasmine Oton and the performers.)

Banneker and Dwight, who have the bulk of the spoken text, are

compellingly voiced by Reginald L. Barnes. Tom Walker handles Jefferson

and Borman ably. Alexandria Joesica Smalls does a delicious turn

as Nichelle Nichols, the African American actress who played Uhura

on “Star Trek” and nearly left the show for opportunities

on Broadway until Martin Luther King told her she was part of history

and needed to stay in her non-gendered, non-raced role as a message

to all of America that “can do” in outer space, in Hollywood,

and on our streets isn’t confined to white, male “heroes.”

I wish I could conclude by channeling Jiminy Cricket crooning “When

you wish upon a star/Makes no difference who you are,” but

we all know it still does. Still, as one-liners go, Neil Armstrong’s

“one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”

regarding his 1969 moon walk, might not be a bad jumping off place

for thinking about Banneker. Just not giant enough in the context

of the cultural constraints of his time. And, oh, please. Can we

make it humankind?

“A

Moon Inside My Body”

The Transfiguration of Benjamin Banneker

January 23 – February 2, 2020

LaMaMa E.T.C. in association with Skysaver Productions

Presented at Ellen Stewart Theatre, 66 East 4th Street, New York,

NY

Thurs. – Sat. @ 7 PM, Sun. @ 3 PM

$25 gen. adm.; $20 Stud./sen. + $1 facility fee

(The first 10 tickets for every performance $10)

Box office: 212-352-3101, www.lamama.org

Reviewed by Beate Hein Bennett on Jan.24, 2020

|

| Banneker Puppet. Photo by Theo Cote. |

Theater artist, director and master puppeteer Theodora Skipitares

has amazed audiences with her inventive, always socially relevant

productions for the past forty years. Her puppet cum actor conceptions

have ranged from intimate miniature solo performances to large scale

ensemble works that incorporate choreographic movement, video and

shadow play constructions, and puppets in shapes of all sizes and

styles that expand the theatrical space all around the audience.

Her theater is primarily a theater of imagery, soundscapes, interwoven

with narrative text of basic information, all of it live with a

minimum of electronic enhancement. Handicraft is the dominant aesthetic

source—the live human presence is the dominant force of action,

inside the puppet.

|

| Soul Tigers. Photo by Theo Cote. |

“The Transfiguration of Benjamin Banneker” is her most

recent conception brought to life with drummers from The Soul Tigers

Marching Band, Inc. , dance students from the Benjamin Banneker

Academy (a public high school in Brooklyn), augmented by professional

puppeteer/dancer/actors, and two actors, Reginald L. Barnes and

Tom Walker, who provide the narrative. Together with the accomplished

artistic team of composer/musician LaFrae Sci, choreographer Edisa

Weeks in collaboration with Jasmine Oton, puppetry director Jane

Catherine Shaw, set designers Donald Eastman, lighting designer

Jeffrey Nash, video design Kay Hines, and film animation artists

Holly Adams, Trevor Legeret & Klara Vertes, with Special Projects

by Jim Freeman, dramaturg Andrea Balis, Ms. Skipitares achieved

a complex performance interweaving all the arts into a contemplative

romp about and around Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806). He was a free

black man, a mathematical genius, self-taught, who dreamed himself

into the planetary realm and thus became an inventor, an astronomer,

and a visionary of a time when all men would be truly seen as equal

regardless of the color of their skin. And in 1791 he challenged

Thomas Jefferson to really live up to his own publicly expressed

ideal of human equality—but was courteously rebuffed! This

historical correspondence is presented in triplicate form: the writing

is projected onto a large screen behind two young black drummers

who translate the back and forth between Banneker and Jefferson

into a drum duel while Mr. Barnes as Banneker and Mr. Walker as

Jefferson read the respective texts.

|

| Funeral of Benjamin Banneker. Photo by Theo

Cote. |

This segment concludes the first part that presents Benjamin Banneker’s

background as the grandson of Bannaka, an enslaved chieftain from

Mali and Molly, an English indentured servant— in her own

right a warrior woman who purchased her freedom and a small tobacco

farm with two slaves as help, and subsequently married her slave

Bannaka whom she freed. Benjamin inherited the title to the tobacco

farm and built his success as a tobacco farmer in Maryland. He becomes

known as an inventor of a clock, writes a respected almanac, and

spends his spare time at night observing the stars and making calculations

that are eventually recognized for their astronomical accuracy.

In 1790 he leaves the farm, the only time, to help survey the boundaries

of the new capital, Washington, D.C. Of course, his fame arouses

not only doubt that as a Negro he is capable of such intellectual

work but also envy. In the last years of his life, he finds himself

under threat, his house is attacked and burglarized, and finally

during his funeral his house is burnt down and with it his manuscripts,

except for one book kept by a neighbor.

Much of this narrative is presented in a series of visually enchanting

and colorful interpretations by the young dancers and puppeteers.

The Banneker puppet, handled by three puppeteers, gains an empathetic

dimension with its large portrait head and a small light like a

soul inside the upper body. The funeral is depicted by a long procession

of miniature puppets while above them hover the huge heads of Jefferson,

Martha W., Susanna, and Sheppard, the savior of Banneker’s

book of memoirs; they comment full of amazement and respect on his

accomplishments.

|

| Astronaut puppet. Photo by Jane Catherine Shaw. |

Interestingly, Ms. Skipitares is not content with simply presenting

Banneker as an 18th century phenomenon of black genius but extends

the narrative by including in the second part, the story of Edward

Dwight who was trained during the Kennedy administration as the

first black astronaut but then excluded by NASA on the instigation

of Chuck Yeager—the sardonic commentary in Dwight’s

own words is poignant. Another astronaut is included, Frank Borman

who was a member of the Apollo team—his words echo Banneker’s

perception of the place and dimension of the human being visavis

space. Borman, while flying around in outer space, observes that

from his vantage point he is able to cover the entire earth with

his thumb. In the theater a miniature Dwight and a miniature Borman

are flying above the audience as we listen to their words. Another

interesting juxtaposition is MLK jr.’s exhortation to the

black actress who performs Uhura in “Star Trek”—again

a puppet in the starship hovers above the stage—that she must

stay with the show; it is the only show MLK and his wife Loretta

allow their children to watch—MLK as a “trekkie”?

Thus Skipitares reiterates the issue of black exclusion and black

accomplishments from the general history of scientific accomplishments

as a cultural blight while her inclusive performance celebrates

the possibility and potential of art as the place of unlimited collaboration.

A small addendum: The USPS found Benjamin Banneker worthy to put

his portrait on a 15 cent stamp.

|