Dorothy Chansky

“One Flea Spare” Proxemics—a consideration of the spatial arrangements between people or things—is a lens much loved by performance theorists in pondering how place and placement inflect human behavior and perception. It was on my mind while watching Playhouse Creatures’ recent sure-handed production of Naomi Wallace’s 1996 OBIE Award winning "One Flea Spare." Wallace’s play pits four unlike people—a middle-aged couple and two young, unrelated strangers—in close quarters under legal order. Who behaves well and who doesn’t only begins to scratch the surface of the questions the play poses about intimacy, morality, opportunism, love, and government policies.

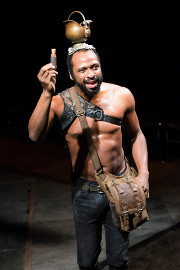

Set it seventeenth-century London, Wallace’s pressure cooker encounters are motivated by a quarantine put in place in response to an outbreak of bubonic plague. The wealthy Snelgraves, Darcy (Marisa Tomei) and William (Gordon Joseph Weiss) are about to end twenty-eight days of obligatory lockdown in their house, when they discover that a rough sailor, Bunce (Joseph W. Rodriguez), and a pushy teenage girl, Morse (Remy Zaken), have sneaked into their domicile looking for shelter. This resets the quarantine clock, much to the Snelgraves’ dismay. Four weeks with smelly interlopers was not what they had in mind. They assume they are entitled to lord it over the pair and to treat them as servants. But the quartet’s individual secrets and inner resources upset the anticipated balance of power. One outsider, Kabe (Donté Bonner), delivers news, accepts bribes, and enforces laws. He serves as a reality check for the housebound quartet. But he is not our guide to Wallace’s world. That would be Morse.

In the pint-sized Zaken’s performance, Morse is simultaneously brazen and a bit naïve in a role limned by the playwright as street-smart, a quick study, and possessed of a sangfroid that comes into play in a chilling moment close to the end of the play. Morse is also a kind of narrator, delivering a poetic introduction and an almost banal conclusion to the events meant to make us ponder what we ourselves might do in the same situation. Which is, of course, four situations. Morse’s commentaries lend a Brechtian strand to the piece, keeping us from total immersion in the story while deepening engagement with Wallace’s language and themes. It is Morse who announces the “nature of secrets. They yearn to be exposed.” William Snelgrave is an imperious burgher with government connections who can’t understand why the rich ever die of the plague, as they are clean. Both he and Bunce have nautical experience, but Bunce has spent his life at sea, while Snelgrave is an official with a kind of desk job. Bunce is forced to scrub the house—over and over—with vinegar, meant to disinfect. When Snelgrave lets the sailor try on his shoes, we are treated to a “walk a mile in my shoes” exercise handled with subtlety. What if Bunce refuses to give them back?

Rodriguez’s Bunce manages triangulates crudeness, sophistication, and sexiness, in a role written to reveal tenderness, self-discipline, training in the school of hard knocks, and, ultimately, cowardice. He returns the shoes, but time and youth are on his side. It is Bunce who unearths Darcy’s terrible secret and offers her solace in what turn out to be the last days of her life. The Snelgraves, we learn, were passionately in love when they married as teenagers, but a household fire left Darcy permanently scarred over most of her body. She wears gloves and high collars to hide her disfigured skin. For thirty-six years her husband has refused to touch her. Both she and her high-handed spouse want to hear about sex from Bunce, but they diverge in where their initial prurience leads. Bunce is able to love Darcy and to note that ultimately you don’t feel with your hands. She loves him back, slowly fingering the open wound on his side that gives him Christ-like symbolism and allows her a way back to intimacy. He, of course, does not die for her sins, nor is he able to ease her last moments when we see her succumb to the plague.

It was the outsider Kabe who knocked the proxemics questions into place for me. In the small blackbox theatre at the Sheen Center—a venue new to me and just into its second season—the play was staged by director Caitlin McLeod in the round. Certainly the audience was close to the actors, but this is an ordinary enough off- and off-off Broadway experience. It was Kabe’s repeated walks around the periphery of the main playing area—the place of entrapment—that foregrounded a feeling we in the audience were outside looking in—i.e., distanced—arguably making Kabe our proxy. And who is Kabe? Part town crier (an official post) and part black market dealer (a shady one), he remains healthy and employed while the main characters struggle with identity and survival. He is both part of the problem and part of the solution. Identifying with his freedom to come and go yielded both relief and a certain feeling of creepiness. Again, those questions of what one herself might do come up, but here from a position of guard, not prisoner. After the performance, I asked myself why I had not felt more engaged with the main characters—why they felt at arm’s length when they were only twenty feet away. My conclusion had nothing to do with the performances, which were all distinct and nuanced. (Well, all right. The brief moments of fully-clothed intimacy between Tomei’s Darcy and Rodriguez’s Bunce did make me catch my breath.) Wallace embeds too much poetic musing in her writing to allow for complete illusionistic immersion. Bonner’s cheeky confidence as Kabe generated a push-pull of “where are my sympathies? Where am I in relation to this situation?" Definitely in and out. One resents class privilege (the Snelgraves) even while perhaps clinging to whatever amount of it one might have (a roof over one’s head and access to food). One cheers for the underdogs (Bunce and Morse) yet sees their opportunism, cruelty, and cowardice as available but less than admirable survival strategies. In and out. Up close and fenced off. Kabe can take it all in and walk away. Is that the desideratum if one can manage it? After the performance I asked an usher about the Sheen Center. Until

two years ago the building was a homeless shelter. Now a comprehensive

arts center, it remains a project of the Archdiocese of New York.

The usher assured me that the homeless shelter had moved a few blocks

away, the current location having become less than entirely useful

in the face of gentrification. One would be an ingrate to diss the

arrival of an arts center devoted to human dignity (http://sheencenter.org/about/),

yet the untenability of a homeless shelter anywhere in Manhattan suggests

a certain connection with the Snelgraves’ incredulity at the

rich ever possibly contracting plague. Vinegar is ultimately no guarantee

of insulation no matter how much of it you can afford. |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |