Three views of "Raisin in the

Sun"

By Carole Di Tosti

By Paulanne Simmons

By Lucy Komisar

|

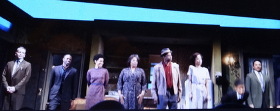

Denzel Washington and the cast of "Raisin in the Sun" shine in a production of unparalleled magnificence.

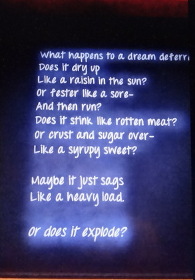

"Raisin in the Sun" by Lorraine Hansberry is a timeless work about social justice and human dignity. The play focuses on how one family attempts to create an honorable life for themselves despite economic hardships. Hansberry would never emphasize this work as a protest play or an appeal for justice for black folk, though its overarching message approaches that. In its time the play was groundbreaking. It forever changed theater. It opened the eyes of white Americans who could not help but identify and empathize with the Younger family in their struggles to achieve the American dream by laboriously carving out a path toward it day by grueling day. With "Raisin in the Sun," Hansberry achieved her own American dream and made history as the first African American woman to have her play produced on Broadway (1959) and the first black woman to win a Pulitzer Prize. The play won a Drama Critics Circle Award as Best Play, ran for two years and was so inspiring and successful that subsequent versions were mounted for film and TV. It has morphed into a musical, undergone a revival on Broadway (2004), and has engendered a quasi-sequel, "Clybourne Park" by Bruce Norris which also won a Pulitzer Prize. Director, Kenny Leon and the current production team have cleverly elected to remind us of the history of this work and Hansberry's importance as an icon of African American literature and theatre by having a recording of an interview with Hansberry playing as the audience enters the Barrymore Theatre. On a screen framed by the stage curtain, Langston Hughes' poem, "A Dream Deferred" is projected. Hansberry used a line from the poem for her title. The themes of the poem directed her characterizations and the storyline of the Younger family, especially the protagonist Walter Lee who dreams of a better life for his family, but finds it impossible to achieve on a chauffeur's salary. However, he hopes to use his father's insurance benefit to become an entrepreneur and open a liquor store with his friends. In the taped interview we listen to as the audience is seated,

Hansberry clarifies key points about her characterizations. Walter

Lee is a determined survivor who will not give up as he proudly

shoulders the mantel of three generations of his family's legacy.

Lena Younger is the dominant mother figure who leads the family;

the mother as the backbone of the family was a role carved out of

the times of slavery when women were allowed a measure of dominance

and men were relegated to powerlessness. Hansberry underscores the

strength of the mother in family unity.

Listening to Hansberry's incisive comments and the interviewer's questions, we are transitioned to the past and into a very different social, cultural and technological time than we live in today. The taped interview prepares us well, for when the curtain lifts on the 1950-1960s era furnishings and Mark Thompson's Set Design of the cramped living quarters of the Younger apartment, we are ready to experience a triple step back into history through the music curation of Branford Marsalis, and Scott Lehrer's Sound Design, Ann Roth's Costume Design and Mia M. Neal's Hair Design. All elements work together with cohesive, natural beauty and singularity. In its initial production "Raisin in the Sun" was a revelation to white and black audiences for its essential humanity and truthful verities of love, respect, dignity and loyalty. This production reveals these great truths and more. It brilliantly elicits the central topics that are as important today as they were in 1959: the gap in employment opportunities between the haves and the have nots; the necessity for all family members to work to make ends meet; the economic difficulty in purchasing and maintaining a house; the importance of living in a community which has a viable, friendly neighborhood; the need for family unity and love to ward off despair and hopelessness. Hansberry chronicles the Younger's changing family dynamic after they receive an insurance benefit. The family's challenges are beautifully conceived by Kenny Leon whose direction has teased out wonderful portrayals: a brilliant, moving Sophie Okonedo as wife Ruth; the humorous and strong Anika Noni Rose as Beneath Younger, and of course, the amazing Denzel Washington as volcanic Walter Lee, and stalwart, faith-filled Lena, Latanya Richardson Jackson. This impeccable ensemble takes in Hansberry's near poetic prose realism and transforms its reality with empathy, then delivers it with love to us. It is their great care that allows these more than talented actors to create individuals we believe and feel and understand in their yearning to define themselves, make their own destiny and achieve inner peace with themselves and their loved ones. As we empathize with the Younger's crises, the message becomes all the more clear to us that the opportunities for whites in Chicago were not the same for African Americans. In the 1950s Hansberry hit the audience with this sledgehammer blow, albeit with a velvet cover of humor and good natured fun (especially through the sibling rivalry and teasing relationship between Beneatha and her brother Walter Lee), well enacted by Washington and Rose. Now, though we assure ourselves that things have changed on the one hand, and the discrimination isn't the same, the reality is that the condition of unequal opportunity still exists and is worsening for all of us. Hansberry is prescient and canny in exposing the cultural values which create the economic inequality and enable the gaps between the haves and what they represent, like George, a crass, wealthy, black materialist portrayed with spot on muted presumptuousness by Jason Dirden and the have nots, the Youngers, who have their faith, pride and dignity, a check from the insurance company and little else of material value. It is through Asagai's (a marvelous, nuanced portrayal by Sean Patrick Thomas) that we see the companion piece to Leyna's determination in his stoicism and self-determination for himself and his people. With wisdom he counsels Beneatha about the sickness of a culture that depends upon a man's death to receive money to live. Through the characters of Asagai and Lena, Hansberry speaks her themes. Hansberry pits Asagai's deep ethical principles against George's materialistic meretriciousness. The playwright emphasizes that the inequity is not governed by race as much as it is governed by social mores and political policies which propagate twisted values. These corrupt values must be expurgated. Lena Younger shows her children how to do this with truth, love and faith. A man theme of the play is that unequal opportunity exists because of unethical economic mores which cause desperation which cause predation. Hansberry's message hits us hard as we discover Walter Lee "invests" his money with scam artist friend, Willy Harris. Willy lured him by spinning American Dream webs of a liquor store and absconded with the money to leave Walter Lee with the nightmare of "his father's blood on his hands." Wonderful in every scene, Washington is particularly wrenching as Walter Lee's fear dawns about what Willy Harris has done and he calls out to him not to do it. It is a terrible blow for Walter Lee. Willy Harris has not only taken Walter Lee's portion of the insurance benefit, he has also taken Beneatha's money which was for her medical schooling. As Walter Lee, Washington's searing pain is acute.

This event is one that devastates us regardless of our class or race; Willy Harris is like a Madoff or Hedge Fund CEO who lured investors and enriched themselves or went bankrupt. It is all the more poignant when Lena Younger forgives and supports her son after Beneatha criticizes him. Lena's timeless, beautiful words tear at our hearts when she implies that the time to love a person is not when they're flying high, but when they are in a terrible, bleak place that Walter Lee is in. In this scene Jackson is breathtaking. The director, the actors and the artistic team's vision of Hansberry's iconic work is magnificently understood. Their combined efforts have pierced any veil of opaqueness that Hansberry may have left to explore. This production shines its light on a mutual and glorious human experience. It is the experience of shared laughter, of tears, of apprehension, of self-disgust, of social reckoning. The actors together evoke in us all the requisite emotions we feel when something happens to change us inside. What this team has realized in every aspect of this production from the staging, to the final curtain is an achievement of which Hansberry, herself, would have been imminently proud for this next generation of viewers to experience. I am just gobsmacked and will probably see it again.

"A Raisin in the Sun" turns 55 this year. Yet the latest revival at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre (the same theatre where the original production was staged) makes the show as bright as a newly minted coin. The drama is directed by Kenny Leon, who two seasons ago directed Lydia R. Diamond's "Stick Fly" and Katori Hall's "The Mountaintop," neither of which made much of an impression on critics or audiences. However, Leon had already made a name for himself on Broadway with his 2004 debut, a revival of "A Raisin in the Sun" starry Sean Combs, Audra McDonald and Phylicia Rashad. And he had directed the 2010 revival of "Fences," starring Denzel Washington and Viola Davis, which garnered ten Tony nominations and won the Tony for Best Revival. Perhaps it all goes to show that a director is only as good as his material. Or it just may be that Leon is once again in his element, working on a classic with veteran actors. "A Raisin in the Sun" is a well-known play. Its title comes from Langston Hughes's poem, "Harlem," which most people know from high school English courses. The play itself frequently appears on course curriculums. And most recently, Bruce Norris's "Clybourne Park," which premiered in 2010 at Playwrights Horizons and landed on Broadway two years later, won a Pulitzer for imagining what happened before and after the events related in Hansberry's play. So why should anyone familiar with the play see this latest version? Most people know all about the struggles of the Younger family: the matriarch, Lena (Latanya Richardson Jackson), who is trying to make the best use of her husband's insurance money; her son Walter Lee (Denzel Washington), who has big plans of getting rich by going into partnership in a liquor store, her daughter-in-law, Ruth (Sophie Okonedo), who is attempting to hold her floundering marriage together; and her young daughter Beneatha (Anika Noni Rose), who is searching for racial and personal identity. And all of this is happening amidst the racial tensions of the mid-20th century. Much of the pleasure in seeing this production is simply in once

again hearing Hansberry's beautiful, evocative language. But hearing

it come from the mouths of such talented actors makes the experience

even better. Washington is 59, twenty-four years older than Walter

Lee in the original script (in this production Walter Lee is 40).

Yet Washington gives a credible performance of a person struggling

toto become a man in a world that insists on calling him "boy." We all know what happens to Langston Hughes's raisin in the sun. It may fester. It may stink. It may sag. And finally, it may explode. Fortunately, Lorraine Hansberry's "A Raisin in the Sun" just keeps getting better and better. Denzel Washington

is a powerful desperate man in "A Raisin in the Sun"

Desperate, full of hope and dreams, wracked by despair, succored by religion, the members of the Younger family spill their humanity in various ways in Lorraine Hansberry's 1959 play about a black family's struggle. The work is based on the experience of her own family, who moved to a white Chicago neighborhood, was attacked by neighbors, and won a 1940 Supreme Court decision ruling restrictive covenants – agreements not to rent to blacks – illegal. Kenny Leon's smart direction elevates to realism over what might have been sentimentality and melodrama. The story is gripping and richly presented. Walter Younger, a brilliant Denzel Washington, animated by conflicting hope and anger, at 40 is a chauffeur for a rich white man. His wife Ruth (Sophie Okone) dour, with a mournful expression, works as a house maid. Okone plays her as rather flat, quietly accepting her lot, though saddened by Walter's despair. Married 11 years, they live in a cramped two-bedroom South Side Chicago apartment with his mother Lena (LaTanya Richardson Jackson), his sister Beneatha (Anika Noni Rose) and his son Travis (Bryce Clyde Jenkin). Lena and Beneatha take the second bedroom, and Travis sleeps on the living room couch. It's humiliating that they have to race to use the hall bathroom shared by another family.

Lena, given a warm and tough portrayal by Jackson, had dreams of owning a house, and she thinks that could happen with the $10,000 she is getting from her late husband's insurance. But Walter wants cash to finance a liquor store with some partners, a way to a life with some dignity. We see a new generation in college student Beneatha, a very lively, vivacious Anika Noni Rose, who wants to be a doctor. She rejects George (Jason Dirden) a rich boy who puts her down with sexist comments: "You're a nice looking girl. That is all you need. I want a nice simple sophisticated girl." Army candy. Hansberry was a conscious feminist.

Beneatha prefers Joseph Asagai (Sean Patrick Thomas), a Nigerian who wants to play a role in his country. Prescient, writing before the mass decolonization of Africa that began about that time, Hansberry has the young woman say, "What about the crooks and thieves who will come into power?" and "there's no progress, just a circle." The charming Rose does a marvelous Nigerian dance in African dress. Representing the old life, Lena slaps her modern daughter for rejecting God. Jackson gives you the feeling that Lena could wrap the world in her arms and succor it. She does that for her family by putting a $3,000 down payment on a house in a white neighborhood, Clybourne Park. (Hansberry's family had moved to Washington Park.)

Trouble comes when Karl Lindner (David Cromer) arrives representing a white home-owners group. In a smarmy fashion, he tells the Youngers that they really wouldn't be comfortable in Clybourne Park. And he offers to buy them out, at a profit. They refuse. Denzel performs a gripping scene when, believing he'll never get any of the insurance money for a stake, he gets drunk and, back home, twists and turns in a rubbery body language and verbal sarcasm that explodes his anguish. Lena, seeing her son burning up inside, gives him half the remaining cash and says to put the rest in the bank for Beneatha's medical school. Walter, of course, is a fool with dreams based on fantasy. You

know he will fail; his first bad judgment was choosing a crooked

collaborator. To deal with that disaster, the family calls Lindner

back to discuss his offer. Hansberry challenges them to take a stand

for their future – as her own family did.

Visit Lucy Komisar’s website http://thekomisarscoop.com |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |