Franca Valeri's play using

a "Tosca" backdrop is sharp, current.

"Tosca e le Altre Due" ("Tosca" and

the Two Downstairs)

March 20 to March 30

Dicapo Opera, 184 E 76th Street, Manhattan (between Third Ave. and

Lexington)

Presented by Kairos Italy Theater www.kittheater.com and Dicapo

Opera

Thursdays through Saturdays at 8:00 pm, Sundays at 2:00 pm

$35.00 general admission; Box Office (212) 868-4444, www.smarttix.com

Reviewed by Carole Di Tosti March 25, 2014

|

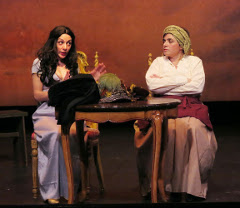

| Marta

Mondell (L) and Laura Caparrotti (R) play women who will witness

the events of the opera, "Tosca," in "Tosca and

the Two Downstairs," a dark comedy by Italian playwright

Franca Valeri. |

The opera "Tosca" by Puccini, is known for

its gorgeous music, piercing violence, dramatic plot and dynamic

characterizations. What is less familiar to Americans is that "Tosca"

is the backdrop for a brilliant satire written by Franca Valeri,

an influential, contemporary Italian woman playwright. Valeri employs

the plot line, main characters and setting of the opera (1800, Rome)

as her fuel to set ablaze various issues which resonate for us today.

With wit and dark humor she exposes paternalism, economic classism

and injustice in Italian culture and society, providing subtle cautionary

threads of wisdom along the way. In her timeless rendition, Valeri's

concepts and themes trend with global currency and poignancy, making

"Tosca e le Altre Due" ("Tosca" and the Two

Downstairs) an amazing play which opera buffs and discerning audience

members will appreciate. Directed by Laura Caparrotti and now at

the Dicapo Opera, the production is running until March 30. The

work is translated by Natasha Lardera.

This is a play within a play. The lead characters are two commoners

realistically and expertly played by Laura Caparrotti (Emilia) and

Marta Mondelli (Iride). These married women from Rome and Milan

are the focal point of the action while the events related to "Tosca,"

Scarpia's capture and torture of revolutionary Cavarodossi, and

Scarpia's attempted sexual bullying of Floria Tosca happen "offstage."

The plot of Tosca runs simultaneously with Valeri's play. However,

we never see the characters in Tosca; we only hear about them through

reports and comments from Emilia and Iride; we briefly hear Tosca

singing. Emilia and Iride give us much to laugh about lower and

upper class culture. Through their characterizations, Valeri provides

an elegant dissection of society and the confines of the powerful.

Valeri has set the scene predominately downstairs, in the doorkeeper's

lodge of the Palazzo Farnese. This is Emilia's and her husband's

residence; Iride waits there for her husband who is in Scarpia's

employ. Upstairs, there are interrogations of prisoners/revolutionaries

like Mario Cavarodossi. They are tortured to extract confessions

or confidences. The women hear and see who comes and goes during

this evening (the events of Tosca). They remark cattily (about Tosca's

allure and other topics) while the agonized screams of those being

tortured occasionally punctuate their conversation. Their presence

in the bowels of the Palazzo is symbolic; this "downstairs"

represents their low status in the hierarchy of power and indicates

that the corrupt political structure is enabled by the weaknesses

of crass and obtuse commoners like these two.

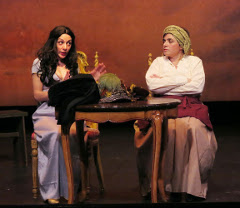

|

Photo

by Lee Wexler/Images for Innovation. |

Emilia is the wife of the porter of the Palazzo Farnese.

Beholden to her employer (the corrupt Baron Scarpia) and obedient

and supportive of her husband (the jailer of the Castel Sant'Angelo),

Emilia is politically compromised. She appears slavishly dense.

Without compunction she upholds the machinations of Scarpia's twisted,

brutal actions as chief of police and dismisses his barbarousness,

as she discusses him with Iride. This is Valeri's sardonic humor

at work. In her characterization of Emilia, she creates one who

appears to be an inglorious, unheroic commoner. We wonder at this

buffoon and comic figure being in a pivotal role. At first glance,

she represents the antithesis of Floria Tosca who is courageous

and defiant with Scarpia. Valeri is particularly wry in trumping

Emilia's base ignorance as Emilia praises her boss' reputation to

Iride. It is not lost to us that Emilia's obsequious, sycophancy

reveals weak mindedness. It appears that her behavior perpetuates

her own oppression and the sufferings of those who would free Italy

and make it a republic, albeit according to French ways.

Like Emilia, Iride appears to lift up the culture's oppression,

classism, feminine stereotypes and paternalism. Iride, an actress

and former prostitute from Milan, is married to Sciarrone who is

Scarpia's henchman and sadistic torturer at arms. As Iride waits

for him to finish his bloody work of the evening (torturing Cavarodossi

to extract the whereabouts of a dangerous political prisoner), she

presents herself presumptuously and superciliously. When she compares

herself to Tosca, Emilia cuts her down with edgy humor. Caparrotti

and Mondelli have crafted these characters with precision and realism

necessary for their later reveal.

The women chatter about what they hear upstairs (as the opera's

plot line continues) and gossip about the other strata of society

related to the characters of Scarpia, Spoletta, Roberti, Tosca and

Cavarodossi. Gradually, the faux walls of personality begin to crumble

and Iride and Emilia confide in each other. Iride reveals that she

intends to be free of her loathsome husband who is brutish and violent.

Her plan is to escape. Even if she has to become a prostitute once

more, she will have independence. She prefers a life of freedom

to one of abuse and enslavement. Iride couldn't have confessed her

soul to a more kind, empathetic and rational friend; Emilia deeply

knows the score living with her jailer husband in the innards of

the Palazzo. She understands the difference between love and hatred

and decides to risk her own life to help Iride. Risking life and

position is an act of noble courage. Yet, in helping to free Iride,

Emilia also frees her own soul and vitiates her own life of paternalistic

oppression.

Valeri's beautiful tie in with the opera comes when the stage moves

into shadow and the figure of a woman dressed in a robe and hood

enters. It is Tosca who has come downstairs while the women have

gone elsewhere. Discovering the large knife Emilia has been using

to cut up food, she takes it and leaves. Tosca, like the two women

downstairs, will deliver freedom to herself and her lover Cavarodossi

by her own hand. With Emilia's knife, Tosca stabs the villain Scarpia

believing she has freed herself to free Cavarodossi. But Scarpia

double-crossed her and had Cavarodossi executed. Tosca commits suicide.

Emilia and Iride refer to her act of throwing herself over the battlements

of the Palazzo.

Valeri's final thematic twist is in the comparison of the two women

commoners and Tosca. The characterization of who they are is clarified

with Tosca's actions. This is brought to the fore because of the

superb direction of Laura Caparrotti who knows the play's themes

and has cleverly teased them out through wonderful performances

and true-to-life-staging and action.

As a result, in this production we realize that the play is not

merely a satire by Valeri who is poking fun at the opera. It is

an explication of women's behavior and choices in a paternalistic,

classist, oppressive culture. The parallel between the two women

and Tosca, despite their different positions, is strong. All women

are suppressed in a society where men get to make the decisions

and hold women as sexual hostages or mouse housewives. Women have

few viable choices; they are labeled as whores if they try to live

by the same standards as men. As a result, when a woman attempts

to control her own life, she often makes poor decisions. Thwarted

by men in control, she is unable to carry herself to freedom. Tosca's

suicide shows that Tosca believes she can never be free of her guilt,

remorse and grief over Cavarodossi's death. Her belief has generated

visions of a hopeless future: she cannot continue in life, seek

redemption and love another. If she is to live to the next day,

Tosca must embrace an identity and life apart from Cavarodossi.

She cannot. She is still in bondage. Valeri presents this as a powerful

feminist trope; Tosca destroys herself because she cannot break

free of herself and escape.

This is not the case with Emilia and Iride. They have found an inner

strength and self-fulfillment. They are able to define who they

are for themselves. They no longer allow a man (their husbands)

to control or define what they can and cannot do. This is revolutionary

power for the time and from two unlikely sources, a wonderful Valeri

irony. Indeed, there is the possibility that both women have been

dissembling all along. By their actions we see that they have experienced

a dynamic inner reformation. They recognize that they can choose

to be free. These measures of freedom born out of Emilia's act of

great kindness and understanding have done more to overthrow the

political machinations of the corrupt and wicked than Tosca's killing

of Scarpia. It is clear that both women are free from the binding

enslavement of love that forced Tosca to fall prey to those like

Scarpia and become a killer like him.

|

|

Photo

by Lee Wexler/Images for Innovation. |

In this clever production, Valeri's play is a vindication

of women as a cautionary tale. There is the way of Tosca and there

is the way of Emilia and Iride. One brings life, hope and freedom,

the other, destruction enabled by the paternalism that oppresses

and harms men and women.

Valeri's ending reveals the way of hope as the women say a farewell

that never ends, well acted by a poignant Mondelli and understated,

humorous Caparrotti. In this superb production we are free to embrace

their hopefulness. Emilia and Iride are emblematic of the potential

power of "the little people" to achieve the deepest honor

and nobility with love and understanding, an honor more courageous

and elevated than Tosca's dramatic act. The production makes Valeri's

message clear. Despite horrific oppression, in one's desire to seek

a just life, the change must come from within. The freedom sought

must first be the freeing of the self from bondages, or violence

and oppression will continue to haunt. In this aspect, the two downstairs

have cemented a bond and worthy foundation to build a power structure

on.