Beate

Hein Bennett

The

Meteoric Rise and Demise of an Artist Dec.

23, 2021 – Jan. 9, 2022

Ishmael Reed whom The New Yorker has called “American literature’s most fearless satirist” has put his investigative mind and pen with this play on the ruthless art market as it devours artists for the ever-novelty-hungry economic elite. The artists are the meat on the potlatch tables of the rich—they become fashion icons and photographic trophies for celebrity self-advertisement. The artist becomes a cult object whose personality and creativity are sucked dry by a vampire market that looks for new blood, the more exotic the better. Such was the ironic fate of Jean Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) who, in the 1980s, rose within less than five years from being a kid street artist to become a celebrated collector’s item—he and his art—though prominent art critics of the time diminished him with the moniker “Andy Warhol’s mascot” –as if he was some exotic animal in Andy Warhol’s “Factory”of fashionable groupies who attained their “15 minutes of fame” by association with the ad-man Warhol. However, Jean Michel Basquiat was an artist who bared his raw young soul in his work and lost himself and his life in the maelstrom of the “cool” fashionable club. This is the subject that Ishmael Reed dissects in his play-- a complex social history of art creation versus commodity marketing, racial identity and economic advantage, personal integrity and the lure of fame and fashion, encompassing the existential paradoxes of the outsider.

Ishmael Reed’s play is structured like a case study, combining forensic investigation with a parallel satire in the style of a noir vampire play. Shadow play scenes are interspersed either as grotesque action or, more poignantly, as Basquiat’s nightmarish dream world -- one particularly impressive dream sequence is Richard Pryor’s ghost warning him of the celebrity cult. Directed by Carla Blank, an ensemble of young actors moves the three types of action forward. The set by Mark Marcante and Lytza Colon with Lighting and Sound design by Alexander Bartenieff divide the large space of the Johnson Theater into three distinct areas, the Living Room of Vampire Baron de Whit on stage right, the office of two female Forensic Experts, Grace and Raksha, on stage left; upstage center is a large backlit screen. While the two Forensic Experts are clothed in medical white coats, the Costume Designer Diana Adelman devised emblematic costumes for the vampire satire: a red-lined black cloak for the Vampire Baron and for his innocent “victims,” the young stage-hungry Jennifer Blue (echo of Warhol’s Factory member Ultra Violet) a colorful gipsy skirt; black would-be-artist Young Blood (echo of Basquiat) wears yellow-green-black trunks that exhibit his muscle-bound black body with Black liberation color symbolism.

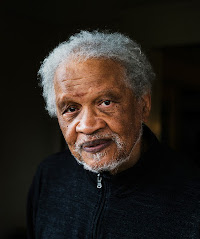

The word-centered script demands a delivery with clear diction in order to illuminate the methodical step-by-step investigation into Basquiat’s demise, his meteoric rise to fame and fortune and ultimate death by heroin overdose. The two Forensic Experts exchange notes on the results of their research: Expert I (Grace), played by Laura Robards is an enthusiastic student of classical and modern art history; Expert II (Raksha), played by Monica Shiva, contributes her knowledge of Caribbean cultural iconography and racist cultural prejudices towards art from the “third” world. Their dialogue is critical to understanding Basquiat’s position as a Black Haitian artist visavis Warhol, the white Pop art icon whose grounding in marketing and advertising made him an astute expert of the mainstream commercial art market; he became the master puppeteer of “cool” and its peddlers, the gallery owners and art critics. Warhol saw himself as Frankenstein and Dracula –in fact, he produced two noir films, “Frankenstein” and “Dracula.” Ishmael Reed’s play owes his satirical couple to this film: the Vampire Baron De Whit, played by Raul Diaz as a diabolical artist, who needs new inspiration, i.e. new blood, to feed his creative hunger, gesticulates wildly and speaks with a bizarrely distorted nearly incomprehensible accent; his sidekick (Art) Agent Antonio Wolfe, played by Jesse Bueno as an evil scheming operator who persuades the Baron that he needs to attract young talents from the newest fashion in the art scene, Neo-Expressionism --Baron de Whit’s favored Abstract Expressionist style is out. This Wolf(e)-in-sheepskin ropes in the young victims with his smooth almost comprehensible Italian accent: Jennifer Blue, charmingly played by Kenya Wilson, hopes to perform for or with Baron De Whit and Young Blood. Ms. Wilson doubles as the dancing Shadow Image (of Basquiat) in the Richard Pryor dream sequence. Two more actors complete the cast: Roz Fox is the irrepressible Detective Mary Van Helsing (echoes of Doctor Van Helsing in the Dracula films) who is investigating the mysterious disappearances of Ms. Blue and Mr. Young Blood both of whom he ultimately finds in the Baron’s basement, barely alive. One other character, the Black Abstract Expressionist painter Jack Brooks appears in front of the “Hottentot Gallery” as a homeless beggar who inveigles upon Young Blood not to lose his soul and art to become a modish fly-by-night—he is played with impressive authority (and clear diction!) by veteran actor Robert E. Turner.

Ishmael Reed alludes to the mutually exploitative nature of the relationship between Warhol and Basquiat. While it is true that Basquiat earned a lot of money once he “ascended” from being a street artist to becoming a gallery darling and fashion icon, he was also forced to produce on an intense time schedule, first in a basement studio space given him by a Soho gallery owner and later in a studio he rented from Andy Warhol on 57 Great Jones Street where he was found dead on December 27, 1988. While painting consumed Basquiat’s life, the present production provides little visual information of his enormous creative output that has remained a hot commodity. His paintings are in galleries and museums all over the world. In 2017 a Japanese billionaire paid $110.5 million for “Untitled”-- a skull-like head with a tik-tok crown. Many Basquiat paintings and self-portraits feature a 3-pointed crown. (Crown replicas can be purchased on e-bay.) The crown bears a striking resemblance to a crowned figure in the central panel of Max Beckmann’s triptych “Departure,” prominently exhibited at MOMA. Beckmann’s crown is a variant of the crown of thorns; he put the crown on all kinds of figures, king or clown—it could represent heroic suffering as well as the mockery of suffering and sacrifice. Ishmael Reed’s case study of Jean Michel Basquiat contains a similar proposition: the Black artist is celebrated as the producer of an object with an economic value mostly benefitting others while the Black human being remains an exotic social outsider. This split in social validation and personal alienation, the human exile, is what ultimately killed Jean Michel Basquiat, “the slave who loved caviar.”

|

| recordings | coupons | publications | classified |