|

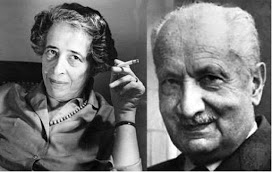

THREE VIEWS OF Beate Hein Bennett A Dark Wind… September 27 - October 14 Who would have thought that two philosophers could possibly be dramatic much less theatrical subjects? Author Douglas Lackey and director Alexander Harrington have managed to extract a thought provoking stimulating performance from two of the most controversial public intellects of the twentieth century: Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), a German-Jewish philosopher and social theorist and Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), one of the most renowned German philosophers to have succumbed to Nazism. The subject of their romantic entanglement, in conjunction with their political trajectories over the course of forty years, from the mid 1920s to 1964, is the dramatic core of this play in a series of 23 concisely scripted scenes.

Hannah Arendt, born into an assimilated Jewish family in Königsberg, East Prussia—the city of 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant—first encounters Martin Heidegger as a 19 year old student in his philosophy seminar at the University of Marburg. She is brilliant and challenges him as a thinker but her eroticism challenges him as a man. He is a respected professor and a married man. The mix of intellectual fireworks and erotic exhilaration erupts into a full-fledged love affair as the political storm in Germany gathers force until Hitler's election in 1933 seals the fate of all Jewish intellectuals (and any political opponents, such as communists and social democrats) first with expulsion from their positions, and ultimately with persecution, obliteration, and death.

Douglas Lackey's play follows the two protagonists as they must reckon with the political reality in terms of their personal relationship, and their conflict is presented through an exhilarating poignant dialogue. Speech as action is underscored by Director Harrington's good use of the large space, designed by Lianne Arnold and Asa Lipton to suggest the variety of locales traversed by the protagonists: Heidegger's office is a desk with a couple of chairs; Hannah's room is a small writing table and a portable gramophone; the famous Philosopher's Walk in Heidelberg is a narrow ramp upstage across the full width of the stage space; Heidegger's retreat in the Black Forest (in Todtnauberg) is simply another raised platform further upstage center; upstage left and right some white birch trunks suggest exterior; a projection screen upstage center shows historic slides of Marburg, Heidelberg, and Freiburg where Heidegger taught, some in conditions before the war, some after the bombings of WWII. Arendt and Heidegger move in those locales with ease and familiarity. To underscore Heidegger's tragic abrogation of any personal moral responsibility from failing to acknowledge the utter corruption of Nazi ideology and political behavior and his submission to the authoritarian manipulations without any resistance, Douglas Lackey highlights some significant events in the philosopher's life, mostly through scenes where Hannah Arendt raises the probing questions about his betrayals of colleagues, his inaugural speech as rector at the University of Freiburg that ends with his triple "Sieg Heil." Heidegger is mostly seen as a feckless man who avoids conflict and justifies his actions as following inescapable orders. During their last meeting in 1964 in a hotel in Freiburg, they exchange two books. Arendt gives Heidegger her book about the 1961 Eichmann trial, entitled "The Banality of Evil" for which she was attacked by fellow Jews as violating the memory of Auschwitz. Heidegger gives her an edition of his book, "Sein und Dasein" [The Being of Beings]—she opens the cover page and discovers that the original dedication to Husserl, his teacher and mentor, was missing. "Why?" Heidegger's quiet answer: "They told me to take the dedication out." A devastating exchange that gives insight into the personal collapse of a thinker under existential pressure. Douglas Lackey has distilled historical research and extracted with few but powerful words the tragedy of intellectual and personal collapse under totalitarianism. A choice quote by Hannah Arendt in bold print adorns the program's back page: "The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e. the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e the standards of thought) no longer exist." How apropos for the present political situation! The actors Alyssa Simon and Joris Stuyck are a superb pair, attuned to each other, finding the nuances, and portraying in subtle ways the impact on their relationship that their external reality imposes: first the exhilarating life of the mind at a renowned university, to threatening Nazi politics and Heidegger's compromises, Arendt's experience of internment (Gurs in France) and forced emigration, geographic distance and age, post-war German reality. To give some contrast and balance to the protagonists, the author included Heidegger's wife Elfriede in a couple of scenes (set in 1933 and in 1959) that show her firm conviction of the Nazi cause to the end—Alexandra O'Daly is a good foil to Alyssa Simon in those two scenes, especially the confrontation between Hannah and Elfriede in Todtnauberg in 1959.

Stan Buturla plays an imposing Ernst Cassirer, another famous philosopher (and Jew) who manages to escape to New York—he is shown first in the famous Davos debate of Heidegger and Cassirer about Immanuel Kant and philosophy's proper inquiry into the nature of existence; according to Cassirer, Heidegger makes mythology while, to Cassirer, science must be the basis for philosophy. Later he has a short scene as Lionel Abel, one of Arendt's New York friends and colleagues. The actors must be commended for bringing to life figures that loom large in the intellectual horizon but are not exactly household names. Hannah Arendt gets ultimately no answer from Heidegger.

The final image on stage is memorable: As she stands behind him with light above, she grabs his head by the forehead with a certain force, clutching his hair and his head, as if she wants to make him say something, her hand gently relaxes into a touch—no words are spoken. Dark descends. Heidegger's retreat "Todtnauberg" in the Black Forest is the subject of Paul Celan's poem by the same title. Paul Celan, a Jewish poet, came to Heidegger on July 25, 1967 in search of an answer, like Hannah Arendt. Paul Celan, born in 1920 in Bukovina, had survived the death camps and written some of the most haunting poems about this reality—he was to commit suicide in 1970. "Todtnauberg" has some lines that resonate with Hannah Arendt's search for Heidegger's soul after the war: "…in the hut, Arendt-Heidegger: A Love Story "Arendt-Heidegger: A Love Story"

"The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e. the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e. the standards of thought) no longer exist." – Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) Thinking is not merely l'engagement dans l'action [engagement in the action] for and by beings, in the sense of the actuality of the present situation. Thinking is l'engagement by and for the truth of Being.The history of Being is never past but stands ever before; it sustains and defines every condition et situation humaine." – Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) In bringing the lives of political theorist and philosophical thinker Hannah Arendt and philosopher Martin Heidegger to the stage at the Theatre for the New City – the play runs through October 14 – playwright Douglas Lackey, known for his historically grounded, highly-researched, and deeply thought out plays ("Kaddish in East Jerusalem," "Daylight Precision," "A Garroting in Toulouse"), has now tackled an historical subject more directly related to his so-called ‘other life', that of a practicing professor of philosophy. Through a series of 23 trenchantly sketched scenes in two acts, the Arendt-Heidegger play billed as a love story, covers the years 1924 when the brilliant, and wide-eyed, 18-year-old Hannah Arendt – some forty years before she coined the eponymous term ‘banality of evil' which brought her world-wide fame – first meets her teacher, the 35-year-old, philosopher Martin Heidegger, soon to be lionized for his book "Being and Time" (1927), and ends in 1964 in a dramatic confrontation between both parties.

The leading characters are Hannah (Alyssa Simon) and Martin (Joris Stuyck), who command the majority of the scenes in the play – we get to take many a walk through the Black Forest with them as they talk about their love, politics, philosophy, and Zionism. We even witness quite a few passionate kisses between them. Also inhabiting the stage is Heidegger's Jew-hating wife Elfride (Alexandra O'Daly), no friend of "Hannah the Jew," and philosopher Ernst Cassirer (Stan Buturia), an adversarial colleague of Heidegger. Both make several effective appearances. In one compellingly combative scene, Heidegger and Cassirer are in Davos, Switzerland participating in a heated debate of opposing views, each eager to debunk the other's positions. The subject being debated: Is Immanuel Kant still relevant in 1929. During the play's 110 heady minutes we are made privy to the thoughts, ideas, and actions of these two major twentieth century thinkers whose very names in this day and age of intellectual forgetfulness are better known then their writings. To prepare the audience for what they are about to see, a note in the play's program informs us that "the facts of the Arendt-Heidegger relationship have been progressively made known by scholars. Martin Heidegger's relationship with the Nazis is also well-documented. We know what happened. We don't know why. This play addresses the 'why' question. As in Shakespeare's histories, much of the dialogue and action is invented. The play goes beyond the facts. But everything in the play is consistent with the known facts." I see this as a niche play for an intellectual audience that is aware, at least on some level, of Hannah Arendt, if not Martin Heidegger, as well as a play for those philosophy-loving newbies with an intellectual bent. The playwright wisely starts this play by prepping the audience, before reverting back to the play's strict chronological order, with a 1952 expository scene which introduces most of the play's topics that we will see unfold in greater detail throughout the play.

In this Act One, Scene One, we find ourselves in Germany at the Freiburg Hotel dining room with Hannah (Alyssa Simon), now 46 and happily married to her second husband, and the 63-year-old Martin (Joris Stuyck), also married with two sons. It is their first post World War II meeting and Arendt, as she tells Heidegger who had been blocked from teaching by the French Military authorities for his association with the Nazi Party, and only just allowed to resume teaching at the Freiburg University, that she is intent on understanding why he has kept silent all these years about his support of the Nazi regime. "I once loved you more than all the world," she says, "and now the world hates you. They hate your silence. How can you remain silent? Martin they put me in a concentration camp! Me and six million other Jews. The Nazi Party did this. YOUR party did this. How can you tell me that terrible things happened to Germany and not speak out about what happened to the Jews? To me? To all the Jewish children shot in Russia, gassed in Poland." "…I still need explanations," Arendt continues. "When you were in charge, when you were the exalted Rector of this Freiburg school, you fired Jewish professors. Martin, you fired (Edmund Husserl 1859-1938) your own teacher! A man we both loved. You can't blame the Americans for that." Heidegger's reply, one that he and thousands of others trotted out whenever interrogated, was that he had no responsibility for his actions, as he was following government orders coming from Berlin. At this point in time, Arendt had already written her first major book "The Origins of Totalitarianism" (1951). Yet to come was her coverage of the 1961 Eichmann trial for the New Yorker Magazine that spawned her most famous and controversial book, "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" (1963), in which she examines the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions. Arendt sided with the latter and used this same defense, most-likely to herself, as well as others, when explaining her life-long friendship with Heidegger. "Arendt-Heidegger: A Love Story," though small scenewise, is huge in its character-driven, thought-provoking ideas, many of which, like racism (both genuine and opportunistic), along with the emergence of right-wing autocratic nationalism, like a virus gone wild, appears to be on the rise around the globe. It is a timely play to say the least. Breathing life into this production is the masterful melding, under the deft hand of director Alexander Harrington, of the actors and technical crew, the latter which played a major part in accurately presenting both time and place. Especially spot on are the scenic and video projection designs by Lianne Arnold and her associate Asa Lipton – every scene had an image projected on a screen that let us know in what city, what location, the action was taking place. Setting the mood to all of this is the continually changing, scene by scene, lighting genius of Joyce Liao.

While all of the actors were simply wonderful, it was Alyssa Simon's uncanny channeling of Hannah Arendt that kidnapped the entire audience. With a cigarette most always in hand – Arendt was a noted chain smoker – Simon radiating intelligence and an overflowing love of humanity, commandeering every scene that she appeared in, just as Arendt is said to have done in real life. At times I felt that I was watching the real Hannah herself. And that is the kind acting, rare as it is, that brings me back to the theater, hoping for such a repeat, again and again.. Note: I might add, in order to more fully understand the ideas and life of these three tremendously productive and deeply intellectual writers and thinkers, I was driven to make a small study of both Arendt and Heidegger, as well as Cassirer, which included reading 2 books, numerous essays, wading through loads of online data, and having many constructive conversations with David Audon, a student and friend of Hannah Arendt and a brilliant thinker himself. Also, extremely helpful were playwright philosopher Douglas Lackey's notes, "Why I Write Plays," "What Is This Play About?," and "Is Heidegger's ‘Being and Time' A Nazi Book?" These invaluable notes can be found on http://arendt- heidegger.com/playwright.htm#notes. [Rubin] Arendt – Heidegger A Love Story By Douglas Lackey Perhaps it's because they're proper Germans or perhaps because they're academic philosophers, but neither Hannah Arendt nor Martin Heidegger seem capable of loving passion in playwright Douglas Lackey's new play "Arendt – Heidegger: A Love Story." I'm inclined to the latter. I know Germans mostly through literature and films. For all their angst and longing for love they have a knack for ending up unloved and lonely at best or in pitifully disastrous suicidal relationships at worst. At least it makes good literature. This play begins in the frantic years of the Nazis rise to power in post-WWI Germany. The romance between Arendt, played with often sympathetic political nagging by Alyssa Simon, and Heidegger could have been a good platform for explaining Nazism and its educated supporters. For me the status of dramatic tension between characters is a prime point for an evening's theater. Joris Stuyck's Martin Heidegger is a calculating academic who is already known to be a Nazi sympathizer. Like a man brushing flecks of lint off his clothes, he feels no guilt after destroying the careers and lives of his university peers. Enter Arendt into his life, a brilliant, Jewish, beautiful young woman student. It's hard to tell if she fell for or is seduced by Heidegger's reputation. Potential moments of tension never take flight. Their attraction is expressed through intellectual repartee. Love between May and December is an eternal philosophic topic. Here we're just given the facts.

The dramatic peak was achieved by Alexandra O'Daly as Frau Elfride Heidegger. Hannah enters the Heiddegger home shocking Elfride who emphatically declares what she feels about their affair, exposes her anti-semitism and declares her personal support for the Nazis. Compared to Hannah's and Martin's polite discussions, O'Daly shows some German courage. Arendt's friend Ernst Cassirer is brought to life by Stan Buturla as a gentle yet strong advisor who understands Hannah's contempt for Nazis while she is in love with one of their chief intellectual heroes. How is this contradiction going to end? It's not as simple as ‘love conquers all.' Hannah is sent to an interment camp and becomes an anti-Nazi, anti-fascist intellectual leader. Her books deal with the ease with which gullible people seeking a political entertainment grasp onto unrealities and political leaders who lead them into disaster. Stabs are made at comparing our present gross Trumpism to the pre-Nazi Weimar world. It's too early to tell where our world is going to end. "Arendt – Heidegger" may be one of the historical signposts to which we might pay some attention. I think so. Look at the versions of reality we're bombarded with. If you try to find explanations in theater, it's there. It always was, is and always will be. [Litt] |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |