Beate Hein Bennett

|

Strange People on Quaking Ground "MESHANYE" by

Maxim Gorky September 13 - September 30, except 18th,

19th, 25th "Meshanye," by Maxim Gorky (1868-1936) was his first play written within less than five years of the Russian uprising at the Winter Palace (1905). In previous English translations under the title "Philistines," it was produced in London and in New York. Owing much to Chekhov, the play takes place in a family living room, within a brief period of time, with a mélange of passionate, frustrated, depressed, cynical, and life embracing characters who launch into torrents of feeling. However, the petit bourgeois milieu is distinctly Gorky. This new translation is modern but with a distinct early 20th century Russian ambience.

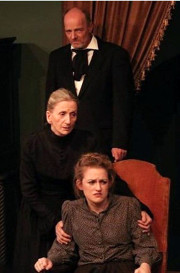

The play is set in the home of Vasily Bessemenov, owner of a house-painting business in a provincial town. The central conflict is between the head of the family and his adult children. He is a simple man, a respected self-made entrepreneur, but of limited education. He provided his daughter and his son with the means of a university education in the hope that they will gratefully achieve a higher social position. However, the unexpected result of his "generosity" is a rift of expectation and communication between himself and his children. Son Peter, age twenty, has been suspended from the university because he joined a student protest; he has absorbed all the ills of angry young men. Daughter Tatiana, age twenty-eight, refuses to marry or even look for a prospective husband; she works as a primary school teacher and is permanently depressed. Bessemenov's wife Akulina tries fitfully to make peace between her permanently enraged and frustrated husband and her relentlessly recalcitrant children. The household, rather expansive in typical Russian (Chekhovian) fashion, also contains assorted relatives and paying lodgers: Bessemenov's adoptive son Nil works as a cargo goods train driver and prospective blacksmith—he is Gorky's ideal "salt of the earth;" Perchikhin, a poor distant relative, a bird catcher/ seller, is a dreamer and drunk; his daughter Polya, working as a maid in the Bessemenov household, is a zesty young woman in love with Nil whom she matches in positive energy; the chorister (almost priest) Terenty, a cynical philosopher and drunk, rents a room in Bessemenov's house; Yelena, a young independent widow and paying lodger, is socially disdained by the senior Bessemenovs but Peter is in love with her; Shishkin, another young lodger, is an activist and consorts with Masha, also activist, primary school teacher and would- be actress. The loyal cook Stepanida, forever irritated by Peter's inconsiderate laziness and Tatiana's stubborn refusal to marry, completes the household. Jenny Sterlin has put together an excellent ensemble of actors—no mean feat for a showcase production with four weeks of rehearsal. She has devised a handsome practical living room (Set Dresser Leonid Grinberg) with the obligatory dining table around which much of the action takes place with the ever present samovar and tea and occasional bowl of kasha for the hungry hangers-on. The costumes (Assistant Debbi Hobson) are well chosen and give an appropriate contour and impression of the period. Above all, she has choreographed the movement and configurations to allow the verbal fireworks—of which there are many among the characters-- to attain rhythm and credibility. The play works like chamber music, in that several voices carry the dialogue forward as characters move in and out of the space, often overhearing each other off-stage and, as they enter joining the conversation, they bring a new tonality. I found the directorial invention of the first preset quite effective, when the entire cast comes on stage, takes their preferred spots as sounds of unrest intrude from the outside through a window. Then darkness, and the ensemble exits. When lights come back up, two young women—one lying, book in hand, on the canapé, the other sewing something at the table— debate the book author's notions of love, disagreeing with each other on all points. The main motif of disagreement and miscommunication is set. John Lennartz plays Bessemenov with a volatile energy unsettling those around him; however, underneath his volcanic eruptions one senses the pain of a man who does not understand those he desperately tries to control. The actor displays an astounding energy but he could release more of his vulnerability and create more differentiation in his feelings of frustration. Isabella Knight, as his wife Akulina, provides a wide range of reactive behavior with her expressive face that can go from radiant smile to pinched reproach, from pained doggedness to proper mistress of the table, from disdainful hostess to frightened wife and mother. While she is definitely subservient to her brutish husband, she has learned to manipulate him. Both are experienced actors who play the give-and-take of an old married couple for whom loyalty to each other subsumes all other emotions. Among the other older characters, Zenon Zeleniuch is an outstanding Terenty, aka Teterev. He launches into his slightly drunk speeches by which he unmasks the various hypocrisies of the old and the young without ever losing control over what and how he attacks; his quiet voice is a musical counterpoint to Bessemenov's loud uncontrolled rages. With his fine face, thin tall physique, and cool demeanor, he also is a wonderful contrast to the other drunk on stage, the "bear" Perchikhin, played by a burly Kenneth Cavett who delivers some beautifully poetic and sometimes comic harangues that are not without covert attacks on Bessemenov.

Gorky portrays the young as a variety of types with differing sensibilities and aspirations about themselves and their future. Thomas Burns Scully portrays Peter as a young angry firebrand who relentlessly disdains his father and despises himself for his dependence on him. Annie Nelson's Tatiana is a depressed suicidal nihilist devoid of any energy for life, except when she is aroused to a brief fit of fury. Ms. Nelson's face can screw itself into a near caricature of bitterness. I wish that she could show her inner conflict of longing to be free while denying erotic stirrings, rather than playing one note of enervated ennui expressed with a barely audible voice. Tatiana's lines could contribute more to the music if the actress used her voice and sharpened her diction, speaking with sustained breath "through her teeth." Aaron Wright as Nil is a wonderful energetic contrast to his two siblings. As the adoptive son he is undervalued by his parents; yet he is confident about his value as a productive man of labor. At one point he throws into Bessemenov's face: "The master is the one who labors." Gorky obviously sees him as the future. His rebellion has a foundation, and he finds his mate in the equally life affirming working Polya played by Ninoshka De Leon Gill as a delightfully strong counterpoint to Tatiana. Fede Rangel as Yelena has her come-uppance with Bessemenov when she pays him her rent and takes his son to her place for a cooling-off period and perhaps to make him an unmarried partner for herself, a proposal that gives Bessemenov almost an attack of apoplexia. Kelli Maguire is a marvelous Stepanida, one of those Russian souls who feed the household and are never short of words to scold their masters and mistresses. Kassandra Perez plays another independent minded and outspoken woman, the teacher and activist Tsvetaeva. (An interesting name coincidence: Marina Tsvetaeva, b. 1892, was one of the great Russian- Soviet poets who committed suicide in 1941.) To have the opportunity to see an excellent production of a rarely performed play by Maxim Gorky, one of the titans of Russian dramaturgy, in a superb new translation should need no extra incentive. |

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |