GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, November 2003

| |

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] "Portraits"

[03] "Recent Tragic Events"

[04] "Omnium Gatherum"

[05] "The Retreat from Moscow"

[06] "Living Out"

[07] "Iron"

[08] "The Night Heron"

[09] "Trumbo"

[10] "Strictly Academic"

[11] "The Colleen Bawn"

[12] "The Threepenny Opera"

[13] Beckett/Albee, with Seldes and Murray

[14] "Henry IV" at BAM

[15] "The Two Noble Kinsmen"

[16] "Hamlet"

[17] "FIGARO"

[18] "Cookin'"

[19] "Arlequin studies"

[20] "The Boy from Oz"

[21] "The Thing About Men"

[22] "Little Shop of Horrors"

[23] "Big River"

[24] "Foreign Aids"

[25] "Nothin' Beats Pussy"

[26] "Rooster in the Henhouse"

[27] "Art and Spirituality: Olivier Messiaen Award"

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to

articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND"

button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal

correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor,

New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters

to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's

INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and

commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international

photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010.

Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

For archival versions of Glenn Loney's past columns, please try our internal search engine.

From The Day of the Dead to Christmas

How Many Shopping-Days Are Left?

Prepare for an Overstock of Christmas Carols,

Hansel and Gretels, Amahls, and Nutcrackers!

OK, it's only Halloween, but some stores have already hung Christmas

Wreaths! Time was when there was no sign of Christmas until the Thanksgiving

Turkey, Pumpkins, and Pilgrim Hats had left the scene. Now, Christmas Promos

begin in September—not to overlook those year-round Christmas Shops. And Halloween

has attained almost the status of a National Holiday, complete with window-displays,

greeting-cards, and specialty shops crammed with Skeletons, Witches' Hats, Ghosts,

Devils, and, of course, more Pumpkins.

In Manhattan, Halloween has been an important occasion for some years—and not just because of the Trick-or-Treat beggars. Thanks to the annual Village Halloween Parade, Fifth Avenue—the city's favorite Parade Route—is left free for traffic on 31 October. Theatre for the New City also has an annual Halloween Party, complete with bizarre costumes.

This past week, several unusual entertainments specially saluted Halloween. Very special indeed was the October 31st opening of Halloween 2003, Beth Griffin's show of anatomical drawings at Spring Studio [64 Spring Street/1212-226-7240]. Medico-legal investigator Jules Lisner shared some grisly secrets of his trade, followed by Zack Zito—author of Monster Madness—bringing Edgar Allan Poe and The Telltale Heart to life, as well as showing Super-8 Horror Films.

Midtown on 42nd Street, there's a vampire-fanged portrait of the Bard of Avon advertising performances in William Shakespeare's Haunted House! This a reprise of last fall's House Tour of Bill's most gory scenes—Blinding Gloucester, for one—presented by the Faux-Real Theatre company at Chashama's 111 West 42nd Street venue.

Chashama has two more theatre-spaces just up the street, at 125 and 135 West 42nd. These have been the scene—from 12 October to 2 November—of Frank Calo's Halloween Festival 2003. This was so successful last year, Calo's Spotlight On Productions have mounted a repertory of over 20 different shows. Among the timely topics are Vampires Suck—The Musical, Dracularama, Golem Stories, Monster in the Closet, Thor's Day, The Witching Hour, Night of the Living Dead—The Musical, and An Evening of Psychos: Stalkers, Sadists, and Serial-Killers. Other less-Halloweeny shows are Philip, Seymour, Hoffman and The Proctologist's Daughter.

Broadway's The Little Shop of Horrors could double as a Halloween Treat. But Henry IV at BAM, way over in Brooklyn, was a Horror Show of quite a different species. Indeed, one could borrow the name of the Mexican version of All Saints Day—known South of the Border as Dia de los Muertos—to describe this miscarriage of Shakespeare as Day of the Living Dead. Pace George Romero!,

Radio City Music Hall opens its annual Christmas Show on 6 November, shortly before Veterans' Day. This sober holiday always falls on 11 November—and it should be a day of Remembrance, not an occasion for colorful window-displays. Nor can it yet even be honored with Anti-War Plays, as it was during the Vietnam War. Such dramas have yet to be written. But Omnium Gatherum—shaken by intermittent bombings—certainly does have resonances. Veterans' Day will have a special sadness this season, as American servicemen and women are daily dying in Iraq, supporting President Bush's dream of bringing Democracy to its unfortunate people.

Speaking of Remembrance, who now remembers that 11 November was originally Armistice Day? For decades under this title, the day celebrated the definitive end of fighting between the Allies and the Germans on the Western Front in World War I. Following the lead of President Woodrow Wilson, Americans fought in that war to "Make the World Safe for Democracy." If President Bush is trying to emulate Wilson in the Democracy Business, he might want to remember that it didn't work out so well. Where are Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia now?

In any case, don't miss the Radio City Christmas Show. There might not be many more of them, and that great auditorium has one of the world's most remarkable systems of stage-machinery and lighting, and one the few surviving great Theatre Organs. With two manuals, so it can be played from both sides of the stage. There is nothing quite like this famous holiday show—scaled-down in recent years, with the Rockettes often out on tour. But there was a time when seasonal shows followed one another in sure-fire sequence. Even as the Music Hall played live stage-shows and major films seven days a week, with production changeovers made on Sunday nights, after the last show. If you miss Radio City's holiday tribute, you can at least savor its productions with Hugh Jackman playing Peter Allen in The Boy from Oz. The Music Hall sequence is Magic with Mirrors!

There will be no November New York production round-up, as your scribe has booked A Passage To India—also a novel, play, and film—returning 1 December. Any Kathkali Dances, Mahabharata, or Ramayana performances on view in Northwestern India will be duly reported here.

No Real War-Plays Yet,

But "9-11" Dramas Take the Stage

Portraits [****]

A massive tragedy is almost impossible to dramatize. The destruction of the Twin Towers—appalling as it was—is hardly on the scale of the Holocaust, yet focusing on the losses of individual lives and those surviving them can provide an effective catharsis. Jonathan Bell's Portraits—at the Union Square Theatre—does this with sensitivity and some sense of Demographics. Thus, those chosen to represent a variety of surviving spouses, families, or friends offer contrasting reactions to their losses. One of them loses his marriage, for his wife calls him on his cell-phone only to discover that he is nowhere near the World Trade Center, where he should have been at his desk. There is even a Muslim woman at a mosque in Washington, DC, who shares her own faith and her fears about backlash. The most affecting of these vignette Portraits is the coupling of a wife—terminally angry that she's lost her husband, helping others to escape—and the deeply grateful mother of a man he directed to safety. Their mutual healing is very touching. Real Catharsis! These women are played by Roberta Maxwell and Dana Reeve. [For the record: Matt LONEY is an understudy: could this be a Family-Connection?]Recent Tragic Events [**]

The premise of Craig White's Recent Tragic Events—at Playwrights Horizons—is that a book-addict arrives for a blind-date, only to realize gradually that he's now with the twin-sister of a woman he once dated. And she's grieving for her sibling, who died in the WTC disaster. He has been feeling guilty, in any case, because he'd advised the dead twin to take a job she was offered in the Twin Towers. This revelation is delayed to the last minute, interrupted by drop-in visits from a Hippie-like scrounger and his pregnant lady-friend, as well as an appearance of Not-the-Real Joyce Carol Oates as a hand-puppet. This Muppet Oates—ostensibly the cousin of the surviving twin—dumps some tart Home-Truths on all and sundry. Heather Graham, as the living twin Waverly, has a wonderful moment of self-realization later in the play, but such an insight is a long time coming in an otherwise self-indulgent and over-extended drama. Colleen Werthmann handled the Joyce Carol Oates puppet with literary dexterity. Unfortunately, playwright White seems to be striving for some stylish structural-devices—and not just hand-puppets, which at least save on actor-salaries. There is a very annoying Stage-Manager who finally reveals that she is not a techie at all. She says—on no visible evidence—that she is in fact an actor! Shades of Pirandello, in the mythic shadows of the Twin Towers! Michael John Garcés staged this sprawling attempt to milk some meaning from the WTC tragedy.Omnium Gatherum [***]

Having seen this socio-political satire in Louisville at the Humana Festival, I was not eager to repeat the experience at the Variety Arts. As there was little else to see—the season getting off to a very slow start—I agreed to check the production out. I am glad I did so, for Theresa Rebeck and Alexandra Gersten-Vassilaros have done some welcome work on their script of what seems The Dinner Party In Hell. In Hell, rather than From, for some of the guests—as the audience gradually learns—are dead. Mohammed, an Arab suicide-bomber, reveals sadly that "There were no virgins." Virgins certainly are not at this Politically Correct table, peopled by a representative selection of 21st Century Types, including a very hungry but dead WTC Heroic Fireman. There's also an Edward Said talk-alike to provide a Moderate Muslim View—and he also offers something like a catharsis at the close. This gourmet feast is presided over by a Martha Stewart from Hell, frenetically and cartoonishly played by Kristine Nielsen. Her work is interesting, but it is Too Over the Top, compared with the other Playwrights' Patsies around the groaning-board. Phillip Clark's ultra-boorish Tom Clancy-type Best-Selling Novelist is—obviously by design—hard to take as well.What made this play work better way down on Third Avenue than in Louisville was the dramatically improved audience-actor relationship in the new venue. At the Humana Festival, most of the audience of American Theatre Critics were up in the steeply raked pit-seating of an arena-type auditorium, looking down at the dinner-table at the bottom of this pit. At the Variety Arts, the audience is much closer and—at least in the orchestra—is looking up at the actors and their feast. This is a tremendous gain in immediacy and impact. Movie-maker Stephen Frears' son Will staged this raucous show to the obvious delight of the audience.

Other New or Recent Plays

The Retreat from Moscow [***]

William Nicholson's Retreat would be a much shorter play without all its quotes from the Oxford Book of English Verse. But it would also be a much less interesting exploration of the break-up of a 33-year marriage without all those poem-fragments. Eileen Atkins is so very good—and totally believable—as a devout Roman Catholic nagging wife that this production is often uncomfortable, even painful, to watch. She cannot leave her long-suffering academic husband alone, goading and prodding him to make declarations and demonstrations of a love he no longer feels. John Lithgow is wonderful as a kindly, passive man who doesn't want to hurt anyone—even though he is constantly hurting himself in so doing. When the worm finally turns, she desperately tries to save her marriage by more goading and invective. When he has left, she tries emotional blackmail and threatens suicide—even murder. Ben Chaplin is apparently a stand-in for the playwright, whose playtext suggests that this is a kind of literary therapy for a man almost as badly bruised by his mother, as he was by his somewhat distant father. As a result, trying to avoid commitment to either parent, he seems even more ineffectual and remote than his father. The metaphoric title—with a front-cloth painted with a copy of an Academic canvas depicting the actual event—refers to the father's evening escapist reading. He ponders the dilemma of Napoleon's defeated officers: should the strong save themselves and leave the weak to freeze to death or starve? Or should they try to help and protect the weak, in which case everyone could be lost? Daniel Sullivan staged this talented trio at the "tiny, little Booth Theatre"—as Dame Edna called it—in John Lee Beatty's strikingly simple set, framed and backed by dense thickets of black branches. The Grand Army could have used those for firewood on the way back to France…Living Out [*****]

Lisa Loomer's Living Out is a brilliantly-crafted exploration of the problems of parenthood of driven professional women and of their struggling-to-survive émigré caregivers. The casual thoughtlessness of the ambitious lawyer-mother Nancy [Kathryn Meisle] contrasts sharply with the kindly solicitude of her Latino nanny, Ana [Zilah Mendoza]. Both women have husbands who have employment problems. Nancy's Richard [Joseph Urla], as a pro-bono Social Cause lawyer, is like a flaky Woodstock survivor. Ana's Bobby [Gary Perez] is a fundamentally proud and hard-working family-man, when he can find work. Airing Nancy's baby, Ana joins a kind of Greek Chorus of comic care-givers. Their tart insights provide an even larger picture of what it is like for low-low-paid illegals and legal immigrants to work for demanding gringos. Ana does Nancy one favor too many, and lives to bitterly regret it. This powerful play at Second Stage was crisply but sensitively staged by Jo Bonney.Iron [****]

Rona Munro's Iron was one of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival's most arresting dramas in the summer of 2002. It was staged by the Traverse Theatre, noted for its premieres of new Scottish and British dramas and a longtime supporter of Munro's work. Having seen that production—which I admired—I must say that I was even more impressed at the Manhattan Theatre Club by Lisa Emery as Fay and Jennifer Dundas as her daughter Josie. Director Anna D. Shapiro helped them achieve almost painful confrontations and accommodations. She was also skillful in deploying them and the two prison-guards in Mark Wendland's striking but simple setting. After 15 years of avoiding any contact with her mother—who was sentenced to prison for stabbing her abusive husband—Josie comes to the womens' prison to see Fay. Both of them have repressed ugly memories: Josie can remember almost nothing of her dead father. Fay does not want to recall any of the abuse or the ultimate horror. The male and female guards do the Greek Chorus Thing, but they also offer useful insights to both Fay and Josie.For the Record from the Theatre-Wire Archive— Here is part of what I wrote about the Edinburgh production of Iron:

Curtain-time—if it can be called that, as there is no curtain in Traverse One Theatre—was delayed almost twenty minutes. It took that long to strike the previous show and erect the metal stairs and catwalk necessary to suggest a women's prison, the site of Rona Munro's painfully ironic Iron.

Josie, a daughter who has not seen her mother in fifteen years, almost on impulse decides to pay a visit to her in prison. Years ago, her mother, the feisty Fay, stabbed her father to death after a drunken altercation. But the daughter can remember none of that, nor even what her father looked like.

The drama is fairly effective and tautly directed by Roxana Silbert. It could make a good film, with Susan Sarandon and Jodie Foster, directed by Tim Robbins. But Munro—who also writes film-scripts—will need to offer more psychological depth to her drama. Some of the emotions and impulses of both mother and daughter, both in the past and the present, are not explored adequately.

Despite the fine performances of Sandy McDade as Fay and Louise Ludgate as Josie—as well as Helen Lomax and Ged McKenna as prison guards—as an alien American, I would have appreciated supertitles. Even with two Scottish grandmothers—and many Augusts spent at the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe—I still find some Scots accents as mysterious as Ancient Celtic. Somehow, I understood Fay to say that her drunken mate had set her on fire. That certainly seemed reason enough to stab him, if she were also drunk at the time.

When I finally read the play—which was also the program, published by the inimitable Nick Hern—I discovered that this was something of a metaphor. Fay does actually say: "He set me on fire and watched me burn and he laughed." But it's only a metaphor, as she's said, just before this—which I did not clearly understand, thanks to the accent-filter: "…my anger flashed over and started to burn me alive…"

The characters and the situation are by no means Scots-oriented. This play could as easily be set in San Francisco, Dallas, or Toronto. And some theatre ensembles there and elsewhere are sure to give it a try…

|

| Chris Bauer and Clark Gregg in Atlantic Theater Comapny's production, "The Night Heron", directed by Neil Pepe. Photo Credit: Carol Rosegg |

The Night Heron [*]

Jez Butterworth—author of The Night Heron—also wrote Mojo, which was also staged by the Atlantic Theatre, in an equally professional production. Unfortunately, I neither liked nor understood what Mojo was all about. With Night Heron, however, I was able to follow its peculiar twists and turns of plot and even psych-out its bizarre characters, the central pair of whom seem to be homosexual gardeners, justly dismissed from employment. One of them hunts—and apparently kills—out in the swampy Fens of Cambridgeshire. The Fens are Edward Bond Country—and his own farmstead could be very near the ramshackle house of Wattmore and Griffin, who seem literary fugitives from Harold Pinter's The Caretaker. Fanatic followers of a new Religious Revelation spell trouble for them, as does a new lodger, a mannish woman just released from prison. She brings them the unsummoned gift of a naked Cambridge University lad. The knockout drops seem to have done for him. But why are we watching all these unstable and potentially violent English Eccentrics in Manhattan's Chelsea District? Butterworth's Grand Guignol and psychopathic characters have a certain Halloween Resonance, but what is the point of this play? David Rudkin's Afore Night Come—with its primal ritual sacrifice in a North Country orchard—was all the more shocking for the seeming normalcy of the farmhands. Edward Bond would at least have found a political point to these moral grotesques. Neil Pepe directed with close attention to detail—even though there seemed to be some ruptured circuits in most of the characters' brains. This is a Mojo no-go.Trumbo [****]

Christopher Trumbo has admirably honored his difficult screenwriter-father with Trumbo, a staged-reading of this brilliant Blacklisted author's prolific and prolix correspondence, now playing at the Westside Theatre. Those who think Ken Tynan and John Simon have outdone themselves in including seldom-used words in their reviews can marvel at the prodigious Trumbo vocabulary. His insights are devastating and often acidly comic. And his satire was sharpened, rather than blunted, by his encounters with HUAC and rampant McCarthyism. Although this show is presented as a reading, the character of Chris Trumbo—a sort of narrator and gap-filler—is acted, not read. Nor, on the evening that I saw F. Murray Abraham wonderfully inhabit the role, were many of the letter-extracts really read. Abraham—in the show for only a week, in a roster of stars as Trumbo—was so secure in most of the missives that he often didn't need to look at his script. This event was staged by Peter Askin in Loy Arcenas' handsome evocation of Trumbo's study.Strictly Academic [*]

A. R. "Pete" Gurney's Strictly Academic title suggests a biting satirical indictment of professorial politics in the Groves of Academe. Randall Jarrell and other writer-professors have already done this with panache. But no, Primary Stages—instead of premiering a brilliant new Gurney social critique—seems to have recycled two indifferent, even obvious short plays which could have been in the bottom of his trunk. With its kinky couple devising disguises and scenarios to enliven their sex-lives, The Problem could have been written as long ago as 1965. So could the second drama, The Guest Lecturer. But the program indicates a premiere performance in 1998. The mythic pre-Greek premise of the latter quasi-comedy is that lecturers invited to talk to a regional theatre's subscribers end up as the Main Course of the post-lecture refreshments. Sort of a Suburban Druid Last Supper, but very labored in authorial execution and player-performances. Frankly, this could have been a Playwriting Thesis Project at any major university. Gurney used to teach at MIT—which would have made a much more amusing academic target. His recent Fourth Wall at Primary Stages was much more ingenious and amusing. Paul Benedict directed a cast including Susan Greenhill, Remy Auberjonois, and playwright Keith Reddin. Perhaps they should have performed one of Reddin's plays instead?

Reviving or Dis-interring the Classics—

The Colleen Bawn [***]

Dion Boucicault's famous Irish melodrama, The Colleen Bawn—with its lecherous villain, treacherous hero's side-kick, and beautiful but bog-bred peasant heroine, secretly married to this landed gentleman—today is something of an historical curiosity. In its time, it drew guffaws and salty tears from thousands and thousands of spectators—not all of them Irish either—from Dublin to London to New York. It was a very popular repertory staple for the Bowery Bhoys. And the Legend of the Colleen Bawn lives on in Killarney, where her statue still sits on a rock by that beautiful lake. Fortunately, director Charlotte Moore knows how to preserve and honor Ireland's drama-heritage without shaming long-dead authors or boring her contemporary audiences at the Irish Repertory. Abetted by set-designer James Morgan, she framed the play with a troupe of touring Irish Players, performing Boucicault's script so broadly that even the most ignorant bog-cutter could follow the plot and get the jokes. But this charming production is not an Evening of Coarse Acting. These are all very professional performers and they play their characters and lines with zest and vigor.The Threepenny Opera [**]

Even some lively Coarse Acting would have improved this Jean Cocteau Repertory revival of the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill Threepenny Opera. It is very true that Brecht didn't want his audiences fooled into believing they were looking at Real Life on stage, but there was never any danger of that even in Berlin at the world premiere of The Threepenny Opera so many decades ago. Brecht devised the so-called Alienation Effect to remind spectators that they were watching a play—and, more importantly, a play with a Message and a Moral. Unfortunately, most of the Cocteau cast were not up to the musical demands of the show, and Mrs. Peachum was downright devastating to listen to. She seemed unaware of her vocal difficulties and belted out her songs with an unwarranted assuredness that gave the Alienation Effect an entirely new meaning. Director David Fuller is to blame for much that went wrong in casting and staging. But Charles Berigan—as Music Director—seemed all at sea with Weill's dissonant score, creating entirely new discords when he touched the piano-keyboard. Several Cocteau subscribers near me thought the production might have embarrassed a high school dramatic society. |

| Marian Seldes and Brian Murray in "Beckett/Albee". Photo credit: Carol Rosegg |

Beckett/Albee [****]

Some radio-ads for the Beckett/Albee program at the Century Theatre suggest that Samuel Beckett is The Greatest Playwright of the 20th Century. Considering the competition—Brecht, O'Neill, Pirandello, Williams, Giraudoux, Miller, and even Anouilh—that is an immense claim to greatness. Frankly, Beckett has long seemed to me as a Minimalist Exponent of Existentialist Drama of Despair in a Meaningless World of Chaos. That is quite heavy enough mantle for a poet to wear around his shoulders. Fortunately for both Beckett and Edward Albee, Marian Seldes and Brian Murray are admirable exponents of the visions and talents of each author. Seldes seems more riveting in Not I than Billie Whitelaw was for director Alan Schneider in London so long ago. She was also compelling in her madly obsessive rounds of heavy walking, in Footfalls. Murray did well with A Piece of Monologue. The duo, however, outdid themselves in Albee's Counting the Ways. This survey of a couple's love in a series of pregnant short-takes was made even more wryly comic by the wonderful timing of Seldes and Murray. Kudos also to director Lawrence Sacharow who so deftly paced this dynamic duo. With a satiric nod to Elizabeth Barrett-Browning's famous love-poem, Albee rings all the changes on a relationship, and his actors even exceed his suggestions.

Shakespeare Studies

Henry IV, Part One [-*]

This had to be one of the worst Shakespeare stagings ever seen on New York's so-called professional stages. Even BAM's stalwart patrons—prepared for a fabulous post-performance party—fled in droves even in the initial phases of this drama-disaster. Why BAM's Artistic Director Joe Melillo decided to open the Next Wave season of cutting-edge performing arts with Henry IV is a mystery. It was already scheduled for Lincoln Center at the Vivian Beaumont, where both parts will be performed, unlike BAM, which offered only Part One. This was more than enough, however. Had Richard Maxwell's actors even tried for Coarse Acting—or the comic style of a touring 19th century Colleen Bawn troupe—there might have been a few laughs. As it was, the performances were so deliberately affectless and amateurish that each scene was successively more painful to watch. Only a few of the cast showed hints of training or talent. The best moments in this godforsaken production were the descents from the flies of successive rectangles of simply painted scenery, in the tradition of 19th century provincial theatres—but not big enough to serve as real backdrops. In fact, a series of such small rough paintings descending and ascending—accompanied by pipes and lutes—might have made a truly original evening of cutting-edge Alternative Theatre.When I returned last month from a series of remarkable and really cutting-edge productions at major European Festivals—some of which ought to be seen at BAM—my first call for press-tix was BAM. But I didn't associate Maxwell's name with House, which I had seen and not much admired downtown. So I asked who Maxwell was: "He's very well known. Think Downtown. Think Richard Foreman." Gawd. Maxwell's nowhere near Foreman in vision, discipline, or fantasy. His dramatic God is Affectlessness: boring actors being bored and being boring people in static exercises in domestic and public boredom for often bored and boring audiences. This may provide a forceful audio-visual comment on Our Society Now for seen-it-all but still hopeful and variety-seeking Manhattanites. It is, however, not useful for Shakespeare.

One prosperous and cultivated BAM patron suggested that Melillo had been so often criticized for not showcasing local Alternative Performing Arts at BAM that this was his answer: even a possible Revenge. To show how awful local experiments can be, in contrast to BAM's customary programming of outstanding international Arts Explorations. This made sense, as there are now so many possible New York venues that local arts-adventurers do not need BAM's stages for pulpits. Then I read a report in which Melillo was quoted as being a big Maxwell fan. Go figure. And go to the Vivian Beaumont Henry IV instead!

The Two Noble Kinsmen [***]

When I first read this Jacobean drama—in a First Edition in the Rare Book Room of the Stanford University Library—the presumed co-authorship of Shakespeare with John Fletcher was still a subject of debate. At that time, only parts of the first half echoed Shakespeare in thought, tone, and expression. The remainder reeked of a much lesser hand, and the entire plot seemed so problematic one wondered why Shakespeare would have briefly emerged from retirement to lend his talents to this strange and not-very-compelling story.Years later, when I was editing Staging Shakespeare—complete with a panel I'd moderated on Richard II, as performed at BAM by the Royal Shakespeare Company—I went to Stratford-upon-Avon to have participants Ian Richardson and Richard Pascoe check the text for accuracy. Richardson was playing Pericles, another drama in which Shakespeare was said to be involved, though not the author of all. In his dressing-room after the performance, Richardson demonstrated for me those speeches which he was certain were Shakespeare's, and which were not. The Bard's lines sprang trippingly from his tongue: the others were clearly awkward, even effortful. And, even more years later, when I saw the Royal Shakespeare's Two Noble Kinsman in the Swan Theatre in Stratford, my original Stanford University reactions were confirmed. I didn't sense any Shakespeare in the second half.

Thus, Darko Tresnjak's new and innovative Public Theatre production is something of a revelation. The writing in performance now seems almost all of a piece, thanks to the cohesion of the visual production and the energy of the cast. It now seems neither sometimes sublime, sometimes abysmal, but more generally workmanlike, serviceable, but not the work of one or two geniuses. No one ever accused Fletcher of genius, in any case. Without Francis Beaumont, what would his career have been?

As The Two Noble Kinsman was initially performed for the Court Marriage of the Elector Palatine Frederic V—later the unhappy "Winter King," rapidly deposed from the Throne of Bohemia—to King James I's daughter, Elizabeth Stuart, the elegant entertainment had to have masque-like diversions and other showy set-pieces. These are evoked impressively—if economically—in David Gordon's unit-set, Linda Cho's costumes, and Robert Wierzel's lighting at the Public Theatre. To achieve the production's stunning effects, the Martinson Theatre has been changed from a thrust-stage with raked seating into a hall-long stage-area, with two stepped triangles of seats angled out from it. This immensely increases the effect of playing-space, preserving the thrust between the triangles of seating. The use of sliding translucent screens—with the two kinsmen's epic battle in silhouette—lends imperial splendor. As the Marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta, reprised from Midsummer Night's Dream—fit for the Marriage of a Stuart Queen with a Winter King—is the locus of the drama, this project could well have attracted Shakespeare, but this is not a Jacobean Masterpiece. The cast was able, with Sam Tsoutsouvas magisterial as Theseus. The women were generally stronger than the men, with Creon's nephews, Arcite and Palamon, ill-matched in David Harbour and Graham Hamilton.

Hamlet [*****]

The New Victory scores again—with another brilliant production, compelling for both kids and parents. How do they find this amazing succession of often quite contrasting productions which yet have the visual and emotional power to engage restless children and teens, as well as delight the adults who accompany them? Or to attract adults who increasingly come on their own, realizing that some of the most interesting international troupes are performing on 42nd Street, not way over in Brooklyn at BAM.Shakespeare's Hamlet may seem either too sophisticated and adult for young audiences. Or too overloaded with Sex and Violence to expose to impressionable kids. As a prelude to Halloween in Manhattan, however, the murders, madnesses, and mysteries which beset and baffle the Court of Denmark held both young and old glued to their seats. Economically and ingeniously staged by Paddy Hayter for Minneapolis's Theatre de la Jeune Lune—white-masked, white-robed male and female figures formed a kind of Greek Chorus, reacting to events and even serving as concealing curtains for sword-thrusts or the sudden appearances of characters—who have in fact been inside some of the robes and masks until their scenes arrive.

The troupe's founders—including Barbra Berlovitz as Queen Gertrude, Vincent Gracieux as Claudius and his dead brother the Ghost, and the remarkable Steven Epp as Hamlet the Dane—all trained in Paris at the École Jacques Lecoq. Thus there is a strong element of the visual and the physical—Mime used with restraint—in service of powerful dramatic passions. Hence the masked, silent Chorus.

Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern are deftly elided from this adaptation and they are not missed. The play loses none of its power—nor its philosophy—in being cut, especially when it is played for youngsters. Elemental scenic suggestions and masks of Fredericka Hayter, with costumes of Sonya Berlovitz, under Marcus Dilliard's subtle lighting, coupled with the musical score of Eric Jensen, make magic on stage.

The company of the Theatre de la Jeune Lune are at home in a cavernous warehouse in Minneapolis. But segments of the ensemble are also on tour with Hamlet and other innovative productions. When the American Theatre Critics Association had its annual conference in the Twin Cities in June, many of us were seeing this brilliantly adventurous company's work for the first time. I was so impressed with Jeune Lune 's version of Beaumarchais' three Figaro/Almaviva novels that I wrote to Dr. Gerard Mortier, Artistic Director of the Ruhr Triennale and to Dr. Peter Ruzicka, Intendant of the Salzburg Festival, to urge them to invite this ensemble with this production.

Here is a Reprise of my Figaro Review

From the New York Theatre-Wire Archive:

For me, the high point of ATCA's recent visit to the Twin Cities was opera-related,

though it had nothing to do with the esteemed Minnesota Opera. Frankly, I was

entranced and astonished at the Théâtre de la Jeune Lune's fantastic and innovative

FIGARO, a hilarious new take on the tale of the Barber of Seville, his lady-love

Susannah, the Count and Countess Almaviva, and the sex-crazed boy Cherubino.

Not only is Mozart's magical score for The Marriage of Figaro a fundament of this opera/theatre production, but Rossini's Barbieri is also quoted. All three of Beaumarchais' Figaro novels are text-bases. Including the seldom-read third novel, La Mère coupable—in which the Countess Rosina bears Cherubino's child, Leon. There are also incidental quotes from such literary luminaries as Charles Dickens—rather in the manner of the late Charles Ludlam's Theatre of the Ridiculous.

Especially interesting is the pairing of actors with singers in the major roles. Fig and Suzanne's earthy comedic performances demonstrate the ensembles' lively debt to the training of Jacques Lecoq's Paris École. As embodied by Steven Epp and Barbara Berlovitz, they also evoke a Brechtian mode. They are paired with actor-singers Charles Schwandt and Momoko Tanno as Figaro and Susanna, who sing the Da Ponte lyrics for Figaro's Hochzeit, and soon begin interacting with their counterparts, as well as singing their operatic roles. This pairing also works powerfully with Mr. Almaviva [Dominique Serrand] and Count Almaviva [Bradley Greenwald], though there is only one Countess, Jennifer Baldwin Peden. In an interesting twist, she sings the Dove Sono over the corpse of Cherubino, played by Christina Baldwin. Above the elemental stage and set-props, a TV-screen highlights segments of the stage-action, greatly enlarged. This is shown against photographs of baroque backgrounds, which make a strong and symbolic contrast with the Brechtian simplicity of the actual staging: Elegance vs. Earthiness…

This New Moon FIGARO doesn't require much to tour. Barbara Brooks conducted a chamber-orchestra of only four members—actually a string-quartet. This production is so innovative, so vital, so charming, so affecting that it should delight opera-lovers who think they have experienced the ultimate Figaros of their time, as well as theatre-fans who think they hate opera. As for attracting young audiences, it should be a major revelation for them. The young woman next to me had no idea who Figaro was, let alone Mozart: "I've got to get the CD!" she exclaimed, enchanted.

Special-Achievement Shows

Cookin' [*****]

This dynamic Korean cookery-show is another energy-charged example of the great productions imported to the New Victory on 42nd Street. I have never seen so much chopped cabbage flying about a Broadway stage—and even into the audience. The premise of the event is that three restaurant chefs have just sixty minutes to prepare a splendid Korean Wedding Banquet. This difficult challenge is even more complicated by the fact that the Mâitre-d' wants them to train his brash young nephew in culinary secrets at the same time. The result is a wild kitchen-choreography of Martial Arts, Kodo Drumming, Cleaver-Juggling, Rapid-Fire Veggie-Mincing, Pop Song Chortling, and Frenetic Acrobatics and Dancing. Something for everyone! Every pot, pan, and utensil in the kitchen was turned into a percussion-instrument. How about some rhythmic Splashing in the Soup? This show drove the kids wild and delighted the grownups. You could see this stage cookery again and again. In fact, in Seoul, it's the longest-running production in Korean performance annals. Over a million people have seen it already. On Broadway, the entire company was celebrated, but the Nephew—Bum Chan Lee—won the charm-sweepstakes. His previous credits include Equus, Animal Farm, and Evita! Should we learn more about what's going on in Korean Theatre?If you are able to catch Cookin' on its international tour, do not miss the opportunity. You might even be invited to get up on stage and take part in the frantic food-processing!

The Harlequin Studies [***]

The signature-programming of the Signature Theatre has been to devote an entire season to the works of one admired—if possibly somewhat neglected—American Playwright. Lee Blessing, Romulus Linney, Lanford Wilson, Irene Maria Fornes, and Edward Albee have been thus honored. But Signature must have run out of Worthy But Not Exactly Mainstream American Dramatists?This season will be devoted entirely to the genius of mime Bill Irwin. It opened with The Harlequin Studies. The title is itself foreboding: "Studies" has about it the aroma of Workshops, Seminars, and Term-Papers. As Harlequin was the master-trickster of the Italian Commedia dell'Arte, his essential character, his plot functions, and routine performance-tricks are certainly worth some documentation, on stage and off. But he and his Commedia fellows have already been amply analyzed in theses, dissertations, monographs, and weighty academic tomes. They are, however, seldom seen on the modern stage—except in Copenhagen's Tivoli Park, where Commedias are still the staple of is historic Pantomime Theatre.

The first half of Irwin's initial show at the Signature was a group of Mime-Studies, in which Irwin's troupe of Harlequins showed the essential movements and tricks. Although very energetic in action, they didn't provide much substance. But then the Commedias were played by touring ensembles which could set up some planks in any city-square or at any crossroads for essentially elemental audiences. Content was hardly to be expected of formula-farces whose outcomes were easily guessed, if not already known.

When I heard that MacArthur Genius Award-winner Irwin was to be the season's star at the Signature, my first thought of was of Irwin walking downstairs in a trunk. In fact, that's my main-image of Bill Irwin in performance. He has all the Commedia tricks down pat, as well as most of the Mime Shtik. He can "do" all of Marcel Marceau's mimes, but, of course, he cannot be Marceau as Mr. Bip. If you are a Mime-Freak, the coming season will surely be a treat, but I worry about seeing Irwin walk downstairs in that trunk too many times.

On the evidence of the Harlequinade which formed the second half of Irwin's first program—Harlequin and His Master Wed—bumptious fun will be the order of the day. At the Tivoli Pantomime Theatre, however, such farces are performed with much more style. And there is a certain magical virtue to a Silent Mimed Commedia, rather than a very broadly played simplistic fable. If there are to be more Commedias during the Irwin Season, it's to be hoped they won't all be walking downstairs in a trunk.

Critiquing Irwin's new show in The New Yorker, drama critic John Lahr put his metaphoric finger precisely on Irwin's essential problem as a Major Mime Exponent. Unlike Buster Keaton, Groucho Marx, Marcel Marceau, and the great historic clown, Joey Grimaldi—all of whom developed Performance Personas—Bill Irwin's bland face seems like putty which can be reworked into any expression. He can do anything, be anything, but as a mime, he has no definitive performing personality. But something could develop over this season…

Musicals Old and New—

The Boy from Oz [*****]

If you remember Peter Allen standing on that giant Legs Diamond electric-sign as it rose up toward the flies, you might have hoped his first and only Broadway show would be a success—not only because it obviously cost so much to produce—but also because Allen wanted so much to entertain and be loved by his audiences. Despite the great popularity of the many songs he wrote and his huge success as the star of Radio City Music Hall spectaculars—the first man to dance with the Rockettes!—I was never a great fan. Perhaps it was his desperate effort to please everyone that put me off. In that, Peter Allen was rather like his goddess, Judy Garland—whose daughter, Liza, he married. [Even in divorce, he had better luck than the most recent hubby, David Gest.] So I was not eagerly anticipating The Boy from Oz, at the Imperial Theatre, complete with a score of Peter Allen songs.The incredibly dynamic Hugh Jackman as Peter Allen has, however, won me over completely. He sensitively plays Allen's need to be appreciated and loved by audiences, but, in himself, Jackman is so at ease, so confident, so super-charged with energy and charm that he might make the real Peter Allen—wherever he is flying and harping—a bit jealous of Jackman's obvious triumph on Broadway.

Without Jackman at its center—and center-stage most of the evening—this trite bio-show might have closed as fast as Legs Diamond. Fortunately, Jackman is its mainspring, wound up by the songs of Peter Allen. But he is well supported by the look-alike Judy Garland of Isabel Keating, the Liza Minelli of Stephanie J. Block, and other strong performers. Mitchel David Federan, as the Young Peter, is a singing and dancing wonder! Robin Wagner's sets are smart—especially his Radio City Music Hall with mirrors—matched by the fabulous costumes of William Ivey Long, and the effective lighting of Donald Holder. Joey McKneeley's choreographies are inventive, in the directorial conception of Philip Wm. McKinley.

The Boy from Oz is obviously going to be a Very Hot Ticket this season.

The Thing about Men [****]

The thing about this charming musical show at the Promenade—The Thing About Men—was that three weeks after seeing it, I could not remember whether Tom or Sebastian was the husband. Or the lover. Possibly because the characters were somewhat interchangeable—which may have made it easier for Lucy to leave one for the other. Yes, I know critics are supposed to take notes: you see them with their tiny flashlight-pens frantically scribbling in their programs, while everyone else is enjoying—or hating—the play up there on stage. I used to do that forty years ago, but my quarterly reports in The Educational Theatre Journal got so long that my mentor-editor, the much-admired critic John Gassner, told me to stop jotting. "Forgetting is also a form of criticism. Write only what you remember. The best and the worst will still stand out. That's enough!"So it says something about the substance of this mis-fired sung-love-story that only the outlines of a really engaging production remain in my memory. It was fun watching all the desperate strategems her first love uses to prevent her from meeting him and his new roommate—her new love—together and finding out that they had become chums. Not to overlook the roommate's potential discovery of their previous relationship. Another charming aspect of this singing-comedy is the strong Male Bonding of the two men who should be rivals.

Perhaps the most memorable production-device is having Daniel Reichard and Jennifer Simard—as Man and Woman—assume an unending series of personas and costumes to frame a variety of richly comic scenes. Their impersonations are a joy! Jimmy Roberts and Joe DiPietro's songs are also charming, if not memorable. Mark Clements staged.

|

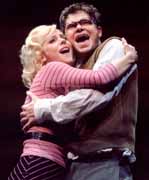

| kerry Butler and Hunter Foster in "Little Sop of Horrors." Photo: Paul Kolnilk. |

Little Shop of Horrors [****]

Translated and transformed from a myriad of small stages and American regional theatres, Audrey II now comes to Broadway as an eventually immense, shop-choking Floral Horror! You should see this colorful show, if only to watch Audrey grow from a small sickly plant to a man-eating monster, gorged with singing human prey! Those who saw Roger Corman's tacky Little Shop of Horrors horror-film all those years ago could never have guessed Audrey would land on the Great White Way, itself an avenue of carnivores. Audrey is well supported—and well fed—by Hunter Foster as Seymour, lately the hero of Urinetown. His sister is still tapping her heart out at the Marquis in Thoroughly Modern Millie. What a Brother and Sister act they would be if the Shuberts or Nederlanders would create a show for them!Admirers of Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin may still scoff at Howard Ashman and Alan Menken's Rock songs, but audiences love them and they are just right for this show. Who could not swing along with "Downtown." Or not empathize with "Suddenly Seymour"? Perhaps the show should be renamed Rocky Shop of Horrors?Very special are Little Shop's all-singing, all-dancing Greek Chorus Trio: Chiffon, Crystal, and Ronnette. And William Ivey Long has created some high stylish outfits for them, with choreography by Kathleen Marshall. As the stage of the Virginia Theatre is filled with Scott Pask's highly stylized ghetto shop and surroundings, there isn't much room for major show-dances. The inimitable Jerry Zaks directed. Actually, he is imitable; I have seen a comic "do" Jerry Zaks!

Big River [****]

T. S. Eliot was convinced that Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn was the Great American Novel. He might have changed his tune when William Hauptman [book] and Roger Miller [music and lyrics] changed it into the Broadway musical, Big River. Aside from the ingenious scenic-solutions of designer Heidi Ettinger [then Landesmann], I did not much admire the transformation at its Manhattan premiere. It seemed an effortful reduction, desperately trying to ingest almost all the many, many incidents in Twain's picaresque novel. A later but similar effort with Twain's Tom Sawyer—again Heidi's remarkable designs were the best thing in the production—was even more labored, though an honorable enterprise.I nearly missed the Roundabout's recent revival at the American Airlines Theatre—not because I feared aisle-seating and in-flight meals—but because I had been making the rounds of major European Festivals. And also because I really didn't remember any of the show's songs as being especially outstanding. But I am an Awards-Nominator, so I dutifully answered the call shortly before the production closed.

Frankly, I am very glad I did so, as this staging was very, very special. It integrated deaf, hard-of-hearing, and non-audially-challenged actors, an initiative of Def West Theatre in Los Angeles—with Gordon Davidson's Mark Taper Center—to create a Big River production with sign-language and unchallenged actors speaking and singing for talented actors who mimed and signed their roles. As all of the latter were also obviously fine actors in their own right, the production had the interesting effect of a highly stylized form of theatre, rather like Kabuki on the Mississippi. Def West is the first professional resident American Sign Language ensemble in the Far West. Daniel Jenkins, the original Broadway Huck, was splendid as both Mark Twain and Huck's speaking and singing voice. Jeff Calhoun staged and choreographed. The handsome sets, costumes, and lighting were the work of designers Ray Klausen, David R. Zyla, and Michael Gilliam.

Solo and Interactive Entertainments

It is not enough for some monologists, solo-performers, and stand-up comics to simply Do Their Thing for an audience. Some insist on co-opting spectators, to make them complicit in the performance-event, or even to shame them into staying put when some disappointed ticket-buyers are heading for the exits. Thus, I try to sit as far away from the stage as possible at such productions. Also, you do not get spit upon by the performer in Full Rant Mode… |

| Peter-Dirk Uys in "Foreign Aids" at La MaMa E.T.C. |

Foreign Aids [****]

Fortunately, South Africa's own Evita, Pieter-Dirk Uys, recently at LaMaMa, is such a charming, thoughtful, and compelling performer that there is no need to flee. In fact, when I was in Cape Town a year ago, I tried to contact him at his own cabaret-theatre in the suburb of Darling, but he had already fled himself, off to another international booking. Uys has transformed a disused railway station into his club: Evita se Perron, perron being the Afrikaans word for station-platform.Uys has been at LaMaMa before and to popular acclaim, as they say. This time round, he reprised his signature-satire, the effusive Afrikaans-equivalent of Australia's Dame Edna, called Evita Bezuidenhout and chock-full of bizarre opinions and observations. Although Uys mocks white South African postures through Evita—"Apartheid? I had no idea what was going on!"—she is a canny lady who often puts her pointed satiric finger on major problems. Sometimes she stabs the finger in a social or political wound and twists it…

Pieter-Dirk Uys also "does" a charming Bishop Desmond Tutu and a lovable Nelson Mandela. We didn't get his monstrous ex-wife, Winnie, but that portrayal ought to be devastating. Because Uys—thanks to videos during Apartheid censorship and his many shows, revues, and tours—is well known in South Africa to blacks, colored, and whites, offense is seldom taken—except by some targets. But The Very Reverend Tutu even gave Uys some Tutu-rings to enrich his Episcopal impersonation!

The main thrust of the LaMaMa show, however, was Uys' concern for the MILLIONS of South African women and children who are victims of HIV and AIDS. Unfortunately, most sufferers are black or colored, so they do not have the funds or access they need for treatment and counseling. Worse—for them and for all South Africans—their indifferent, ego-driven black President denies the existence of AIDS and has insisted—as has his crony, Zimbabwe's racist President Robert Mugabe—that Aids is a White Man's Disease. In one misguided governmental effort to curb the spread of Aids, thousands of condoms were distributed, but instructions had been stapled to them, making two punctures in the rubber, rendering them useless!

Pieter-Dirk Uys now spends much of his time traveling around South Africa to schools and community-centers to entertain with his impersonations and to show kids and parents how they can protect themselves and, if so unlucky as to fall ill, how to take care of themselves. But ignorance and denial is endemic, and Aids Cocktails cost a lot of money—which most black South Africans do not have. They do not have even a few Rand. At LaMaMa, after the show, Uys accepted donations for Aids victims, in return for handmade beaded Aids Ribbon,s created a group of South African women trying to survive from day to day.

Unfortunately for Aids victims in Africa and elsewhere, US Government-sponsored initiatives to curb any kind of Social Disease cannot distribute condoms, or even advocate their use. Fanatic American Religious Fundamentalists—even before the Born-Again Bush Administration—have prevailed on the Congress and other DC agencies to promote ABSTINENCE and FAMILY VALUES as the only defense against Aids, syphilis, gonorrhea, and genital herpes. Not to mention as a defense against creating more unwanted children in overextended families with no father on hand. Sadly, Abstinence is not an option when a woman or a young girl is raped, or a wife is forced to give her husband his "Conjugal Rights."

Even more horrifying, as Uys reports it, is the black South African "Urban Legend" that a man with HIV can be cured by having intercourse with a virgin, young girls being the usual victims. This idea was current in Mozart's day, but it has probably been around since the time of Julius Caesar. Men are terminally ill and dying of Aids, but it is the women and children who seem most afflicted and least able to protected or help themselves.

Pieter-Dirk Uys and Evita are on a journey now, with a Mission and a Message.

Nothin' Beats Pussy [*]

|

| John Fleck amid family memorabilia in "Nothing Beats Pussy." |

A Rooster in the Henhouse [**]

Irish-American John O'Hern has been an at-home father, while his wife makes a really good salary as a professional. He has also worked as an actor, so the idea came to him that he might help the family funds by creating a solo-show about his experiences as a new dad, both at the neighborhood pub and as a lone man among at-home moms with their precious offspring. This is the essence of the title, and it's apt, as O'Hern—in performance and in his own text—seems pretty pleased with himself. He is a totally unself-conscious performer, but a difficult childbirth, reprised in steps, followed by diapering and other aspects of baby-care are not my idea of a Great Evening of Theatre. Even on Theatre Row, where you take it as it comes along. This show was extended, but the night I saw it, there were only a handful of people in the auditorium and we were ordered to sit up front. I hung back, to maintain some Aesthetic Distance. O'Hern can tour this show, for there are surely many young couples with babies around America, who could relate to it, if they could find a sitter so they could go out to the theatre.

Out-of-Town Events—

Arts and Spirituality in Western New York State:

Olivier Messiaen Award at Quick Center for Arts

It is always An Occasion to be invited to the French Embassy's Services Culturelles

in its handsome mansion on Fifth Avenue. You are greeted by a small Michelangelo

statue in the downstairs chamber. Upstairs, French wine freely flows, and exhibitions

of paintings or photos line the walls. Currently, this visual treat is a series

of photographs of Paris districts and shops from early in the century.

But the Special Event was to honor the distinguished French pianist, Mme. Yvonne Messiaen-Loriod, widow of the great composer, Olivier Messiaen. An annual award in his honor is being inaugurated by New York's St. Bonaventure University, located in Western New York State. The award itself was just presented at the handsome Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts at St. Bonaventure. This culture-complex by Flynn Battaglia Architects looks like a Post-Modernist version of Vienna Jugendstil of the era of Josef Hoffmann and Kolo Moser!

Joseph LoSchiavo—who made his name in Manhattan with splendid small-scale opera-productions—has moved from his recent post as Director of Hunter College's Sylvia and Danny Kaye Theatre to the Quick Center, where he is developing an interesting new program devoted to The Arts and Spirituality. As the University is dedicated to the ideals and examples of St. Francis of Assisi, this promises to be a program worth watching.

Metropolitan Opera tenor Kenneth Riegel—who distinguished himself in Messiaen's epic opera, Saint François d'Assisi—was on hand both in Manhattan and at St. Bonaventure to salute Mme. Messiaen-Loriod. She is the first recipient of the Olivier Messiaen Award for the Arts and Spirituality.

Copyright and copy; Glenn Loney, 2003. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| museums | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |