GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

INNOVATION AND TRADITION

OPERA AT THE MUNICH FESTIVAL 2003

By Glenn Loney, July 28, 2003

"Der Rosenkavalier"

Caricature of Glenn Loney

by Sam Norkin.

"Entfürhung aus dem Serail"

"Rinaldo"

"Tannhäuser "

"La Traviata "

"Das Gesicht im Spiegel"

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."How to contact Glenn Loney: Please email invitations and personal correspondences to Mr. Loney via Editor, New York Theatre Wire. Do not send faxes regarding such matters to The Everett Collection, which is only responsible for making Loney's INFOTOGRAPHY photo-images available for commercial and editorial uses.

How to purchase rights to photos by Glenn Loney: For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

SEARCH THE NEW YORK THEATRE WIRE

Even before Sir Peter Jonas left ENO—the English National Opera—to become Intendant of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, his predecessors, Wolfgang Sawallisch and August Everding, were in the vanguard of opera chiefs giving old operas a New Look. This has been happening all over Europe for some time now. But it has proved a mixed-blessing, especially for opera-lovers who would like what happens on stage to relate in some visible way to the actual libretto. Not to overlook the possibility of a visual resonance with the powers of the music…

At the Salzburg Festival, however, under Gerard Mortier's direction, some astonishing innovations—visually striking though they certainly were—did not really serve the operas effectively. Fortunately, in Munich, most of the Re-Visions of old Opera War-Horses have proved both memorable and consonant.

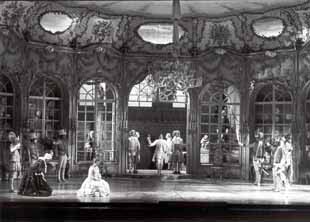

BEFORE THE SILVER CHERUBS FELL OFF--Jürgen Rose's splendid Munich setting for "Der Rosenkavalierl" in 1989. Photo: ©Sabine Toepffer/1989. "Rosenkavalier" Returns

Of the several State Opera stagings seen this past July in Munich's Neo-Classic National Theatre, only "Der Rosenkavaliel" remained resolutely traditional. This is still played in the once beautiful silver baroque settings of the brilliant designer Jürgen Rose. But the physical production has been too long in the repertory, and it shows its age.This was originally a co-conception of Rose and the Viennese actor and stage-director Otto Schenk. In the years since this "Rosenkavalier" was premiered, however, Rose has pursued a pathof ingenious innovation, creating some of the most powerful stage-visions to be seen anywhere in Europe. Schenk, on the other hand, has had a fondness for what he once called Romantic Realism: His "Tannhäuser " at the Met—with designer Günther Schneider-Siemssen—is in fact a very handsome example of this production-genre.

In the Marschallin's bed-chamber—at least in Munich—the walls have been shuffled about so much from storage to stage and back again that some of Rose's most lovely silver-rococo decoration has been damaged. Or knocked off entirely… You can see the ghostly stains of cherubs which have vanished. Those that remain remind old-timers of how glitteringly lovely this Act One setting once was.

But I've just studied an essay which suggests that this chamber should look a bit worn, as though the unseen Field Marshall has little interest in keeping up appearances on the upper floors of his great palace, largely leaving his wife to her own devices and amours.

This is an interesting point, but to it is added the observation that, in production in Act Two, the newly-rich and newly ennobled Herr Faninal should manifest a strong visual contrast to the Marschallin's environment, with bright, costly, vulgar over-ornamentation in his new Vienna palace. In Munich, unfortunately, this setting also shows wear and tear.

[The most effective Faninal Palace-setting I've ever seen, highlighting his lack of culture and new riches, was the one August Everding introduced at the Hamburg Opera. The walls of the Grand Salon had been turned into a Library, with shelves of books reaching from floor to ceiling: each shelf-section was topped with a letter of the alphabet: A, B, C, D…]

The abrasions of long years of use in the repertory do no damage, however, to the scenic-flats of Act Three's rustic inn. In fact, this entire production still works very well, cast with such talents as Cheryl Studer [Marschallin], Franz Hawlata [Ochs], Katharina Kammerloher [Octavian], and Camilla Tilling, a lovely young Sophie. Peter Schneider conducted.

Nonetheless, it would be most interesting to see what kind of new vision Jürgen Rose would bring to the opera now. The late Herbert Wernicke was on the cutting-edge at the Salzburg Festival some seasons ago with a "Rosenkavalier" which had stylish off-stage set-elements reflected on-stage in mylar panels. Of all the beloved Opera War Horses, "Rosenkavalierl" certainly needs a New Look. At least in Munich, where most of the repertory has been innovatively rethought since the arrival of Intendant Peter Jonas. It seems almost a relic now…

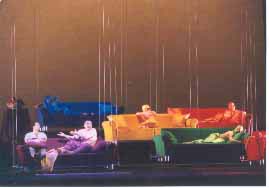

SINGING COUCH-POTATOES--Mozart in Munich: "Abduction from the Seraglio" cast performs on Flying Sofas! Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/2003.

Mozart's "Entführung aus dem Serail"

Staged Aloft on Six Flying Sofas!Munich opera-regulars—who surely have seen a variety of stagings of Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio—were greatly baffled by Martin Duncan's new staging, set by co-conspirator Ultz, who is a one-name, one-note designer.If anyone in the audience had never seen the opera before—or even if he or she actually had read the synopsis of the libretto—what happened on the vast stage of the National Theatre would still be a mystery. Entführung is a German Singspiel—not an Italian opera—which means that the dialogue between the arias and duets is spoken, not sung. But it is very important in developing the characters and advancing the plot.

Unfortunately, in Munich's new production, stage-director Duncan has opted for a possibly "Politically Correct" approach: Perhaps he fears that the Bavarian State Opera may be attacked by Islamic Turkish Terrorists?

Certainly, Mozart—and his librettist Stephanie—were having fun with the idea of Virginal Christian Women trapped in a Turkish Harem, constantly in danger of the lusts of the Pasha and his Harem-Master. The massed Armies of the Ottoman Empire had been repelled at the gates of Vienna in 1683. The memory of that threat to Christendom was hardly a hundred years old. But Western fascination with Islam and the Mysterious Middle-East was on the increase, and Entführung helped feed that interest.

Today—despite the noble behavior of the Turkish ruler, Bassa Selim, who gives Konstanze and Blondchen and their Christian fiancé-rescuers their freedom—this hoary stereotypical vision of Turks and Islam is embarrassingly passé. But this is still an opera with some wonderful music. As is The Italian Girl in Algiers, which is now also an embarrassment with its racial and religious stereotypes.

Martin Duncan has turned Mozart's wonderfully comic 18th century opera into an ultra-modern vision of an old Turkish Tale, told by a black-Burkah-clad female narrator. This divorces the dialogue entirely from the central characters, who are left largely with their songs, which are now ripped from any dramatic context. Most of them now make little or no sense dramaturgically. Konstanze's heroic Martern aller Arten aria is almost meaningless in this Story-Theatre framework.

But it was Duncan's and designer Ultz' decision to fill the air above the stage with six colorful suspended sofas—on which most of the action or in-action took place—which annoyed, amused, or baffled both critics and audiences.

These Flying Sofas, however, did not just hang there. They flew on wires, up and down, back and forth. Luxuriously and gleamingly upholstered in bright basic colors—Yellow, Green, Blue, Red, Purple, Orange—they provided moving venues for sinuous airborne ballets by harem lovelies. Pedrillo got Osmin drunk on one of them, though the dramatic purpose of this was in no way clarified by such staging.

Tall tables loaded with luscious fruits were in fact worn by deftly moving extras, who could keep them near the moving sofas, davenports, or chesterfields. All of which looked as though they'd just arrived from an IKEA showroom.

AS a prelude to the actual action of the opera, a group of young men—who seemed to be soccer-fans—divested themselves of their clothes on the forestage. They then proceeded to emasculate themselves, showing the audience jock-straps stained with blood. The Politically Correct implication of this gratuitous gesture was unclear. Although in some Islamic areas—where slavery has not ceased—eunuchs are still created, they are castrated as young boys. Not as mature men… What kinds of fantasies are racing through the minds of Ultz and Duncan anyway?

Music-critics—not only from Munich but from all over Germany—had a field-day mocking this pretentious production—which was also roundly booed at its premiere. Some headlines will give an idea: Kastration "live," Auf fliegenden Sofas, Fliegende Haremsdamen, A Tale with Six Sofas, Singers on Sofas, Swinging Sofas, Serail auf dem Sofa, What Are Football Fans Doing In the Harem?, There Blood Spurts on Their Underwear, and World Peace Appeal in Diapers.

Some critics invoked memories of Goethe, whose early interest in Orientalism took the literary form of his West-Östliche Divan. Thus, this headline: Mozarts west-östlicher Diwan. Or Auf dem west-östlicher Diwan: Mozarts Entführung.

Or these headlines: A Weak Hour's Lesson in Orientalistic, An Ethnographic Turkey-Discourse, A Chatty Hour with Songs Included. And: Wer Mozart so vergessen kann… Who could so completely forget Mozart, indeed?

British conductor Daniel Harding—part of this English production-team—was also roundly blamed for his eager participation. Certainly he spurred the orchestra on, to keep the proceedings from sinking into incomprehension.

Only the Pedrillo of Kevin Conners emerged with vocal and character credits, despite the appalling stage-direction. Malin Hartelius did her best as Konstanze, but the sofas were stacked against her. Natalie Karl also tried to make her mark as Blonde, although the effort was doomed by her director. It was embarrassing to see a mature singer like Paata Burchuladze have to perform Osmin with his shirt off. Will opera-singers soon have to start going to the gym for workouts on their abs? Roberto Saccà, as Belmonte, was almost a cipher in this Flying Sofa Circus.

All that was missing were the Flying Carpets. Well, not exactly: Bassa Selim—as a character on stage—was nowhere to be seen. But at least the outlines of Mozart's opera remained.

A week later at the Salzburg Festival, another cutting-edge production of Entführung premiered. The basic plot was almost nowhere to be detected. The director had used the opera as an inspiration for a completely new concept. These innovations are now called "after Mozart" or "after Verdi." The idea of two lovely Christian women held prisoner in a Muslim Turkish Harem had been replaced by a fantasy on young Middle-Class Western Marriages. Including explorations of kitchen-appliance wedding-gifts! With so many brides and grooms on stage, this looked like Seven Times Seven Brides for Seven Brothers!

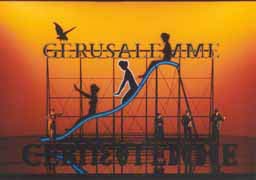

SLIDING INTO THE HOLY CITY--Munich Opera's "Road Map" for Peace in the Middle East, as revealed in

Handel's "Rinaldo". Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/2003.

David Alden's Post-Modernist "Rinaldo": A Long Way Off from Handel's Holy Land

Georg Friedrich Händel didn't have to worry about offending Muslim sensibilities with his opera "Rinaldo" in the London of his time. Even had there been a large Muslim community, there was an Islamic prohibition against attending theatrical performances—which still stands, especially in Saudi Arabia.For that matter, the Ottoman Empire was still regarded with suspicion and wariness in Handel's time. Although the

Turks had been driven from the gates of Vienna in 1683, they continued to occupy much of Southeastern Europe until the 19th century. Greece won her freedom only in the 1830s, and the Turks remained in Bulgaria until late in the century

For that matter, the Christian Crusades had proved—possibly like the recent and ongoing adventures in Iraq—an ultimate disaster. Blessed by various Popes, Crusader Knights had secured the holiest of the Holy Sites in the so-called Holy Land. But only for a century or so, before the Arabs drove them out again.

Thanks to the Italian poet Torquato Tasso and other fabulists, however, fantastic tales of the heroic deeds of the Crusaders and the Christian Conquest of Jerusalem long ago had to take the place of pride in an actual on-going Occupation of the Holy Land. Handel's "Rinaldo" was inspired by Gerusalemma Liberatta, which suggested that the brave Christians were up against much more than armies of ignorant Infidels.

Rinaldo's most dangerous enemy is Armida, the Sorceress Queen of Damascus. Talk about Weapons of Mass Destruction! What if President Bush had accused Saddam Hussein of Witchcraft—as well as Nuclear Warheads?

Well before the recent White House campaign of mis-information about Iraq's threat to American Security, David Alden, the brilliant American stage-director, had the ingenious idea of up-dating "Rinaldo", making it something of an American Radical Religious Right Crusade. In fact, he put a self-promoting contemporary Protestant Christian Evangelist center-stage in his Munich staging. This production premiered before the Bible-Thumpers flew out to Iraq to convert the Muslims from their mistaken beliefs. Billy Graham's son-and-heir, the Rev. Franklin Graham—who has the President's Ear, so to speak—even denounced Islam as "a wicked religion."

It might be an interesting idea for the White House to invite the Bavarian State Opera to bring this "Rinaldo" production to the Kennedy Center. It now seems even more timely—and satiric—than it did several seasons ago.

But some of the design-jokes of Paul Steinberg [sets] and Buki Shiff [costumes] are less amusing, seen for the second or third time round. And, although Ann Murray continues to soldier-on in Handelian castrato roles in Munich, the amazing counter-tenor David Daniels was much more impressive as Rinaldo when this production premiered. Ivor Bolton's enthusiastic conducting, however, shows no diminution in his dedication to and affection for this staging.

For the Record, here are some notes on the Munich "Rinaldo" premiere in 2000 AD:

"Rinaldo" [the brilliant counter-tenor David Daniels], dressed like a New York mafioso, wants to reclaim the Holy Land for Christianity with his stalwart comrades. That they are a trio of talented counter-tenors makes this production a very special treat. A fourth counter-tenor, Charles Maxwell, gets to play a drag-role and the Christian Magician, for which he's dressed like a fantastic Voodoo Conjure-Man.

Each of this interesting quartet of talents has a distinctive vocal quality which goes very well with the character being played. Counter-tenor David Walker is properly brusque and conspiratorial, playing a Mafia Capo as Goffredo, the Crusaders' General. Eusaztio [counter-tenor Axel Köhler], his brother, is a wavy blond-haired Christian Evangelist, a real TV Bible-thumper. In Alden's production, he is something of a cult-figure. At the close—with Jerusalem at last freed of the Saracens and in Christian hands—he's shown smiling on the cross, rather like the Christ Crucified this summer at Oberammergau in the Passion Play. It's all a send-up of the purported reasons for the Crusades. They weren't so much about Faith as about Power and Booty. Unfortunately, there was no Crude Oil in Jerusalem. There still isn't…

The initial setting of Alden's "Rinaldo" has walls covered with the symbolic Hand of Fatima. As they are leading a Christian Crusade to liberate Jerusalem, this must be a Muslim stronghold they have already conquered. In any case, it doesn't appear to be a very historic mosque, for, as with all the other settings, it is terminally trendy. The Magic Palace of the Saracen sorceress, Armida [Noëmi Nadelmann] is a seriously skewed travesty of a 1950s living-room.

A German critical colleague dated it 1970s, but its central floor-lamp could have been designed by Ray and Charles Eames. Not only was its perspective off-center and its yellowish floor steeply raked, but its walls were bold, clashing pink and orange. A cut-out of the fleeing heroine, Almirena [Dorothea Röschmann], popped out of the stage-left wall to reveal the poor captive girl filling the cavity.

As often happens in such plots, the witch falls in love with Rinaldo, and her original lover, the Saracen King of Jerusalem, Argante [Egils Silins], is smitten with ""Rinaldo"'s Almirena. The source of all these amorous, fabulous, and military high-jinx is Torquato Tasso's epic, Gerusalemme Liberatta.

But what is this Holy City that our Crusader heroes finally conquer for Christ? It is a glowing sign on a high scaffold, spelling out Gerusalemme. An eagle—or is it a raven?—perches on the initial E. These letters are repeated on the floor, so large and solid that the characters can walk on them. Between these two Gerusalemmes there stands a tall swooping slide, illuminated in neon, with three black cut-outs of girls—outlined also in neon—sliding down.

When it's time to besiege the Holy City, Daniels and Almirena bring out armfuls of little plaster statues of Jesus. These are ranged across the front of the stage, and at one point they fall like a line of dominoes. Or the Radio City Rockettes, dressed as toy-soldiers.

In the libretto, both Argante and Armida, defeated by the superior power of the Christian Crusaders, convert. This may have seemed a formulaic Happy Ending—along with the lovers reunited—for both Tasso's and Handel's audiences. It parallels Shylock's forced conversion to Christianity in The Merchant of Venice. Alden forestalls any such triumphal Christian self-righteousness, however, by making it very difficult for Argante to change religions.

In the final scuffle for Jerusalem, Argante—in full armor, with a big sword—is no match for Crusader heroes. His head is cut off at one blow. His body slumps to the floor. Some distance away, his head continues to sing!

OPERATIC ARCHITECTURE--Monumental settings overwhelm Munich Opera's "Tannhäuser ".

Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/2003".

Short Shelf-Life of Post-Modernist Revivals: David Alden's "Tannhäuser " Already Shopworn

Even after four years in the Munich repertory, David Alden's witty, satiric "Rinaldo" staging still has visual power. That cannot be said, however, of his bizarre Deconstructionist vision of Wagner's "Tannhäuser ". Using a vast Post-Modernist architectural façade—featuring the large-writ legend: GERMANIA NOSTRA—Alden and his set-designer, Roni Toren, have metaphorically attempted to translate "Tannhäuser "'s tragic tale into an operatic survey of 20th century German History.

The late Goetz Friedrich was the first to suggest that the furious knights at the Battle of Singers in the Wartburg were, in fact, proto-Nazis. This outraged some Bayreuth Traditionalists, but it had a certain resonance that was re-inforced when Friedrich reworked the production for television.

Unfortunately for such Modernist Concepts, they often lack validity or consonance, in relation to the central character and to the plot. Cute ideas which make sense only for the first fifteen minutes of an opera. Not to overlook the problems of Wagner's score not being related to such up-datings, as well.

"Tannhäuser " is not an Anti-Fascist Freedom-Fighter. He is a Romantic Outsider who has deliberately broken all the religious and sexual taboos of his time. Worse, he has even boasted about his high old times in the Venusberg before his saintly and beloved Elizabeth and the entire court of Medieval Thuringia.

Elizabeth—sensitively interpreted again this past summer by the lovely Emily Magee—has to endure a great deal of suffering in the libretto. And Wagner's demands on her voice are also taxing. Add to that the directorial indignities David Alden has heaped upon her, and she deserves a medal for Hazardous Duty, as well as the bravos and applause she justly wins.

In this cast, the Wolfram of the admirable Simon Keenlyside was clearly the winner of any song-contest on the stage. Robert Gambill's "Tannhäuser " was not persuasive enough. As Venus, Waltraud Meier provided a powerful—if not very sexy—performance. But she can do no wrong in her fans' eyes—and ears. Jun Märkl conducted.

For the Record, here are some notes on the Munich "Tannhäuser " premiere in 1994 AD:

Most imposing—and most controversial—of the new Munich Festival productions, however, was the new "Tannhäuser ", conducted by Zubin Mehta and created by a team led by director David Alden and assisted by designers Roni Toren, Buki Shiff, and Pat Collins. With Vivienne Newport providing choreography in the Venusberg—which was also equipped with a moving crocodile, possibly a relative to the Tyranosaurus Rex seen in Munich's Giulio Cesare. The basic set was a sky-cyc with clouds and a long white back-wall, variously architecturally decorated as scenes changed. Stage-left there was a lone white classic pillar leaning toward stage-right, a possible visual metaphor for a sexually spent "Tannhäuser " [Rene Kollo, this time in excellent form, a world-weary man of middle-age!], after his sessions in the Venusberg. Actually, these encounters didn’t look very orgiastic—but then they seldom do, even at the Met. With the knight-poet "Tannhäuser " at one end of a long formal table and Venus [Marilyn Schmiege] at the other, sexual fun in the Venusberg looked rather like dinner with Barbra Streisand in a Malibu grotto.

At the famous War of Singers in the Wartburg, customarily "Tannhäuser " is the only one who shocks, passionately departing from the rules of courtly love and minstrelsy to tell the straight-laced lords and ladies what sensual love is really all about, images which enrage them and deeply wound his love, Elizabeth [Nadine Secunda]. In Alden‘s odd production, all the other contestants wear their sexual kinks and obsessions almost literally on their sleeves, concealing nothing. It’s a bit like Medieval Role-Playing Therapy. But up-dated, with some modern costumes. Very amusing, but it does skew Wagner’s intended point about the tragic but very human difference between his doomed hero and the other Minnesingers—who play by the rules. Instead of a romantic historical fantasy set to music, this becomes, for a while, only slightly more elevated than Charles Ludlam’s Theatre of the Ridiculous parody of Wagner’s Ring.

Instead of the Wartburg’s Teure Halle, designer Toren offered the white wall, bearing huge letters: Germania Nostra. It looked like a Nazi motto carved on a monument by Albert Speer. What’s more, the court looked and behaved like Nazis as well. This outraged some in the audience, but it already did that years ago at Bayreuth, when director Goetz Friedrich suggested the same interpretation in both costume and acting. There’s something else odd about this staging. After "Tannhäuser " is banished—off to Rome to seek Papal absolution—the entire Kingdom of Thuringia seems to fall into ruin, like the Wasteland at the end of Parsifal. But "Tannhäuser " is not Parsifal, even if David Alden may want to be another Charles Ludlam.

Sensitive and Stylish Up-Dating Of Munich's "Traviata " Still Haunting

The major danger of up-dating either "Traviata " or "Bohème" is possible damage to the audience's Willing Suspension of Disbelief. Tuberculosis can be cured! But in Puccini's period-libretto, Mimi's friends can barely afford medicine for her—and it comes too late. Of course an up-dated modern Violetta could easily afford medical assistance. Even in Verdi's period-context, staying quietly in the country with Alfredo would have done her a world of good, had not Germont Senior arrived to destroy her dream of love.Fortunately, in Günter Krämer's more modern Munich staging, the focus is so strong and clear on Violetta and her doomed love that a trip to the Mayo Clinic or a Magic Mountain in Switzerland don't even seem medical options. Working with designers Andreas Reinhardt/sets, Carolo Diappi/costumes, and Wolfgang Göbbel/lighting, Krämer has created a highly stylized "Traviata " production—now long in the Munich repertory—that makes this tragic tale seem almost timeless. The very stylish Art Deco scenes of partying and gaming make their Minimalist Effect mostly through the very smart costumes: formal-dress and lovely gowns on parade!

An enormous crystal-chandelier is all that's needed to suggest the glitter and the glamour of Violetta's desperate pursuit of pleasure. Later, sunk on its side on the floor, it signals the decline of her life-style and deflation of her hopes. Minimalist simplicity in scenery, elementals in costume and lighting: these production-values require a great deal of the singers. The stylish concept cannot succeed without transcendent performances.

The problem with this production—which I have now seen a number of times—is largely in its casting. When a lumpish Alfredo is paired with a wan Violetta, the magic of the stage-environment makes the duo look even more pathetic, sometimes grotesque. And a soprano who makes Violetta seem shrewish is a disaster.

Fortunately, this past summer Anna Netrebko's Violetta and Rolando Villazon's Alfredo were Romantic Magic on stage. They made this aging staging look wonderfully new. And this was not only because of their splendid voices and nuanced emotional interpretations of their arias and duets. As actors—using their faces, gestures, movements, and entire body-language—they heart-breakingly embodied the thwarted lovers. Anna Netrebko is a splendid soprano, but she is also a very beautiful woman, made even more so by her ability to become so radiant in such a demanding role. Rolando Villazon made a very handsome, passionate partner and betrayer. He is clearly a young tenor to watch.

The ending of this sad story becomes a kind of transfiguration in Krämer's brilliant production. Instead of coughing herself to death in her sickbed, Violetta walks slowly in a long white gown toward a distant blaze of light, as though she were Passing Over… It is a radiant closure to her short, bitter, disappointing life.

Fabio Luisi conducted, with a sense that what was happening on stage between the two lovers really was For the First Time…

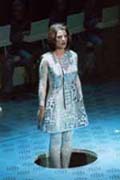

BATTERIES NOT INCLUDED--Justine, the Cloned Woman, clothed in micro-circuits for The Face in the Mirror.Photo: ©Wilfried Hösl/2003. Desperate Need for New Music and New Operas:

No Image-Reflection in "Das Gesicht im Spiegel"Sir Herbert Read called it The Myth of Progress in the Arts. In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, the idea that Music, Art, Theatre, and Literature should also advance and changewith the times took hold. Wagner's advice to create new works—instead of imitating past models, forms, and themes—is periodically invoked when an innovative or experimental artwork is unveiled. If it fails to find appreciative viewers and critics—whether on the wall, the page, or the stage—the backwardness of the potential audience is often cited as an excuse for popular or critical disappointment.And so it is with the World of Opera. Early in the last century—the 20th, not the 19th—some very impressive young composers were creating new operas in Italy. Some of these works achieved almost immediate success—even at the Met—but they gradually faded from opera repertories. Only to be rediscovered at the Bregenz Festival and other experimental venues.

Unfortunately, in recent years, most new operas—either in Europe or the Americas—have glittering, hyped premieres and then disappear without a trace. Stage-director Tom O'Horgan—who made his mark with Hair on Broadway and The Trojans at the Vienna State Opera—explained to me the reason for this: Commissions, subsidies, and grants from foundations and opera-ensembles eager to encourage experiment, innovation, and cultural advances.

The real problem with such commissioned operas, he insisted, was that the composers had made their names with other musical forms. But they really knew nothing about opera, especially opera-theatre. After the Symphony, the Quartet, the March, the Sonata, and the Song-Cycle, the only musical mountain left to climb was the Opera-Berg. Such composers often had no sense of dramaturgy: no experience of what works on stage.

Even new quasi-operas so topical as John Adams' Nixon in China or The Death of Klinghofer at least had the newspaper headlines on their side. But they both lacked really interesting, powerful confrontations between, or among, major characters of some dramatic stature. Nixon and Kissinger were cartoon-stereotypes.

After the initial hoopla of their premieres and tours, what opera-houses seized these productions for permanent places in their repertories? Who would want to see/hear The Death of Klinghofer more than once? Even Death in Venice is not a repertory-standard.

Thus, it seems problematic whether American audiences will see any time soon Jörg Widman's new opera, "Das Gesicht im Spiegel". It had its world premiere this past July in Munich's historic Cuvilliés Court Theatre, a glittering baroque jewel-box. This framing-venue provided a strange visual contrast to an opera celebrating multi-media electronic, video, and digital technology, in service of a Post-Modernist fable about a marriage gone wrong—as a result of cloning-experiments.

The opera's production-values—as well as its very trendy topic—might well make this an item for the Next Wave at BAM, however. But it is unlikely to enter the repertory of New York City Opera or the Met. This is partly the fault of the score, which is also technology-oriented. Although press-hype suggested that Widman is one of Germany's most brilliant young composers, the music for his The Face in the Mirror did not support that claim.

Perhaps the elegant poster for Gesicht im Spiegel provided a more appropriate visual metaphor. It showed a mirror with no reflection in it. The production, of course, is not entirely faceless.

In fact, it is filled with multiple electronic images of logos and its central character, Justine [Julia Rempe], an exact clone-copy of Patrizia [Salome Kammer], who is chief of BIOTEC, which specializes in cloning experiments. The four-hander cast is completed with Milton [Richard Salter], a bio-engineer for the firm and Justine's teacher/trainer, as well as Bruno [Dale Duesing], Patrizia's husband and business-partner.

The plot-devices involve Bruno gradually falling in love with his wife's clone, her insane jealousy, and Justine's developing real human feelings, with attendant despair at the impossible situation into which her creators have plunged her. As a Mad-Scientist, Milton has distinct dramatic possibilities. As does Justine, who could certainly be much more interesting than the Bride of Frankenstein.

But the libretto of Roland Schimmelpfennig is not dramatically effective, nor are the characters interesting enough. It wouldn't make the critical grade as a play without music. Alas, the score doesn't enhance the fable very much. Instead, the production-values have to do that. Costume-designer Martin Krämer has created an impressive outfit for Justine: she rises from a hole in the stage in a dress and hose which are covered with large-scale silver micro-circuits. Justine's agonized face is projected on a video-screen overhead, as are Biotec logos, obviously inspired by Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo da Vinci.

Lab operations at Biotec are facilitated by a corps of little blonde Munchkins, tapping away at uniform banks of laptop computers. They look like Nibelheim dwarfs in Bayreuth's current RING production. Actually, they are impersonated by boys from the Bad Tölz Knabenchor.

"Das Gesicht im Spiegel" was commissioned for the Bavarian State Opera by its Intendant, Sir Peter Jonas. As Jonas was once chief of the English National Opera, it is just possible that this production may travel to London. But it is also, visually at least, the kind of contemporary novelty much loved at the Houston Grand Opera. And, of course, also at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which has no ensemble and no repertory. As with The Death of Klinghofer, Gesicht im Spiegel would be performed several times there and then archived in some critics' memory-banks.

Curiously enough, one of the finest modern operas I have ever seen also had its World Premiere in Munich in the Cuvilliéstheater. This was one of Hans Werner Henze's earliest opera efforts, and it was a revelation musically and dramatically. Titled Elegie für Junge Liebende—or Elegy for Young Lovers—it recreated the sad tale of two young lovers who have been sent out on a walk in the Alps, even though the malicious poet who urged them to go knows a terrible storm is coming. He will imagine their last hours, exposed on the mountain-side, as the subject of his next Great Poem. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was terrifying as the obsessed poet, who had just lost his longtime poetic subject when the frozen body of a long-dead bridegroom was recovered from an icy crevass. What the young couple discover in the minutes before they die is that they don't really love each other. In fact, they hardly know each other… But the new poem is a huge success. Nonetheless, Henze's heart-breaking opera—while critically admired—was not a popular success, and it did not find its way into the Munich repertory. Nor did a later World Premiere in the Cuvilliéstheater, Aribert Riemann's Melusine, a Nixie, or water-sprite, love-story similar to Ondine and Rusalka. The only time I have seen Henze's Elegy for Young Lovers, after forty years ago in Munich, was in a three-performance revival by the Juilliard School Opera Theatre. This is very sad, especially as Henze just premiered what he has promised will be his last opera, L'Upupa, at the Salzburg Festival. It was also a festival commission, but nowhere near the artistic inspiration or quality of his elegiac earlyElegy.

Missed Munich Opportunities

With a very tight schedule and so many productions on view at the Bavarian State Opera, there was time only for an evening at the Gärtnerplatz-Theater for a performance of Carl Orff's charming fable, Die Kluge. So I missed new stagings at the Theater der Jugend's Schau-Burg, the Residenz-theater, now run by Dieter Dorn, and Munich's historic city-theatre, the newly restored Jugendstil-jewel, the Kammerspiel. Next summer, for sure! [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2003. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| home | welcome | search |

| museums | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |