Lucy Komisar

|

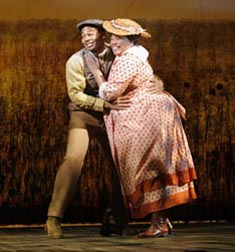

| "The Color Purple" -- Victor Dixon, Felicia Fields. Photo by Paul Kolnik |

Book by Marsha Norman.

Music and lyrics by Brenda Russell, Allee Willis & Stephen Bray.

Directed by Gary Griffin.

The Broadway Theatre, Broadway at 53rd St.

212-239-6200.

Opened Dec. 1, 2005.

Reviewed by Lucy Komisar Nov. 28, 2005.

Buy Color Purple Tickets

This brassy, bluesy, R&B and gospel melodrama, based on Alice Walker's novel, is a feminist cry of pain and rebellion, an operetta-style protest in the tradition of "Porgy and Bess." It's a moving and memorable production. Playwright Marsha Norman generally succeeds in pulling the play out of the book through a series of vignettes that span four decades.

The central character, Celie (LaChanze), is a sad child-women abused by her stepfather (JC Montgomery) and by "Mister" (Kingsley Leggs), the man who buys her as a servant and bedmate. The fact that she never calls him by a name establishes her status as "thing" to "the man." From 1909, when she is 14, Celie suffers more trials and tribulations than any soap opera heroine. Even Mister's kids are nasty to her.

The play, though often sentimental and corny, is spirited, from the colorful gospel opening number, to the comic Greek chorus of three droll gossipy church ladies, Kimberly Ann Harris, Virginia Ann Woodruff, and Maia Nkenge Wilson. Their jazzy skat number is the show-stopper.

The script offers a tough political approach to the plight of black women in the segregationist South, a place where they were oppressed by black men as well as by whites. And where black women often had to be tougher to survive. The female characters show the variety of solutions black women found.

Sofia (Felicia P. Fields) is a self-confident hefty and redoubtable lady who won't take gaff from her lover, whose answer to men's threats is to pick up a rifle ("Hell, No!" she sings), and who suffers tragically from her refusal to kowtow to the mayor's wife. This production does not sugarcoat history.

Celie's sister Nettie (Renée Elise Goldsberry) is adopted by a preacher and his wife who take her to a voyage of self-discovery in Africa. Now the three lady busy-bodies are shown as Africans who admonish Nettie that, "You need a husband and children." Still the wrong answer! However, the switch of venue to Africa, along with hokey native dancing, seems forced and is never believable.

Celie takes the hardest road, suffering as a near slave through what seems an inordinately slow consciousness-raising. It takes forty years – is that the Israelis's forty years in the desert?

The triumph of Celie and the women is the resounding proclamation of their sense of self. Think feminist revival meeting.

In this morality play, the male characters are caricatures, the kind that audiences used to hiss at. Are men ultimately victims too? Even that is suggested by "Mister's Song," when he wonders "who I really am."

There's some leavening comedy. The cute and sexy "Any little thing I can do for you" by Sofia (Fields) and her boyfriend Harpo (Brandon Victor Dixon) is a delight. So is the energy, spark and charm of local girls at the visit of Shug Avery (Elisabeth Withers-Mendes), who made her escape years ago by being a courtesan.

There's also a hint of political lesbianism. Shug Avery seems to prefer a woman when she's not working for her keep.

LaChanze is persuasive in her transformation from frightened victim to strong woman. Felicia P. Fields excels in her supporting role, giving an amazing performance as the brutalized Sofia. Their singing, and that of the rest of the cast, is the show's strong point.

John Lee Beatty's spare sets are subtle evocations: a field of corn edged by the wood slats of a house; a bedroom with a brass bed and bureau; foliage and sky. Paul Tazewell's costumes are charming turn-of-the-19th-to-20th-century dresses, suits and derbies.

Director Gary Griffin uses screens and projections to enhance the magical scenes and dances of this energetic pop musical. Music and fantasy make bearable the violence we see. But the emotional reactions of the audience members makes it clear that nothing eludes them. This is in the best tradition of American musicals, not escapism, but strong commentary about our world. [Komisar]