LUCY KOMISAR

Artistry and Politics Animates This Season's Musicals

Forget the morose assertions that the musical is doddering or dead. It has never been more relevant and alive. Whether they are new works or revival or adaptations of novels, when musicals dare to confront real social issues, they are vibrant and exciting and - if the music and lyrics and acting keep pace - they are exhilarating theater.

Look at four good examples that came to the stage this season. Their excitement comes from a mixture of artistry and politics.

|

| Jennifer Westfeldt, Donna Murphy, "Wonderful Town," photo Joan Marcus |

"Wonderful

Town"

Book by Joseph Fields & Jerome Chodorov. Lyrics by Betty Comden &

Adolph Green. Music by Leonard Bernstein. Script Adaptation by David Ives.

Directed and choreographed by Kathleen Marshall.

Al Hirschfeld Theatre, 302 W. 45 St.

212-239-6200

Opened Nov. 23, 2003.

Reviewed by Lucy Komisar Dec. 4, 2003.

With the backdrop of 1935 Greenwich Village and the sounds of thirties jazz, this affectionate feminist confection tells what happens to sisters Ruth ( Donna Murphy) and Eileen (Jennifer Westfield) when they arrive from the provincial mid-West and discover, one, a pervasive contempt for women intellectuals, and two, the casting couch.

It's all done with clever pulsating dance numbers and witty tuneful songs. A smashing opening ballet is a brassy pastiche of village people. Director-choreographer Kathleen Marshall gives the show a zingy elegance. The sisters warble about "Ohio yo-yo-yo." They harmonize in rich soprano and alto tones.

There are lessons in songs such as "One Hundred Easy Ways" to lose a man. They all involve showing woman letting it show that she is smart. That's Ruth, a sharp lady who wants to be in publishing.

Eileen's troubles start when she looks for an acting job and discovers that producers want to hold auditions prone.

There's a clever lampoon of macho Hemingway mixed with the sense of a Noel Coward divertissement. And a good humored joke about ethnic stereotyping when a line of policemen do an Irish jig; one of them is black.

"Wonderful Town" is funny, witty, clever, joyous. It makes you think. It's subversively feminist. It lifts your spirits. The sultry, jazzy dancing doesn't hurt. Nor does Leonard Bernstein's scintillating sounds. John Lea Beatty's pastel sets are so evocative you wish you could buy copies at the annual art show at Washington Square Park.

|

| Kristin Chenoweth, Idina Menzel, "Wicked," photo Joan Marcus |

"Wicked"

Book by Winnie Holzman. Music & Lyrics by Stephen Schwartz.

Directed by Joe Mantello.

Gershwin Theatre, 222 W. 51 St.

212-307-4100

http://www.wickedthemusical.com/

Opened Oct. 30, 2003.

Reviewed by Lucy Komisar Nov. 5, 2003.

This behind the scenes revisionist view of "The Wizard of Oz" is a political allegory about racism and discrimination. It's fascinating as a literary work and stunning as theater. Based on the novel by Winnie Holzman, it's an updated Animal Farm. It's a play that exists on two levels, one for the kids and another for adults, who will find it intellectually stimulating. It's Oz before Dorothy got there.

You might think this was a typical high-tech Broadway extravaganza. After all, a dragon belches smoke from the top of the proscenium and a huge witch's hat flies around. (The set wizardry is by Eugene Lee.) Susan Hilferty's costumes are great gobs of color and feathers.

But then there's the subversive ironic story of the self-absorbed good-girl (good witch) Glenda (Kristin Chenoweth) who is so full of herself she declares, "It's good to see me isn't it?" Then, "No need to respond, that was rhetorical." Glenda is utterly self-involved, has 24 pairs of shoes, and is popular and empty-headed - though good natured.

Her princely boyfriend, by the way, is appropriately shallow and pretentious.

Expect a lot of tongue-in-cheek references. There's the bedraggled 19th-century mob, for example.

So, getting down to the racism: Elphaba (Idina Menzel) the wicked witch is green! And there is privilege and discrimination aplenty. The girls go to a private school for the upper classes, where Elphaba is a charity case.

The rich kids don't like to be reminded of how these class divisions happened: "I don't see why you can't just teach history, instead of always harping on the past."

The professor (William Youmans) is a goat who, like many other animals, has forgotten how to speak. He writes on the blackboard that animals should be seen and not heard. By the way, animals are also forbidden to work. Well, what can they do? The professor declares, "There is so much pressure not to." Elphaba is indignant: "It can't happen here."

This is the lightest, frothiest political treatise you ever saw, with a bubbly Chenoweth holding forth in a lilting soprano, and stomping about with cute, quirky gestures. Idina Menzel is a passionate, intelligent Elphaba.

The vividly green Elphaba sets out for the Emerald City where wizard Joel Grey is out to stop subversive animal activity. His tactic? Inventing an enemy for people to coalesce against; he even puts wings on monkeys and makes them spies. Storm troopers chase around and arouse shivers. The wizard's contraption of cogs and wheels makes us wonder about the evils of industrial society. His snooty press secretary spins lies.

It appears that people are willing to grovel and submit to feed their ambition, that they are not comfortable with moral ambiguities. A message for our times, for all times. And a superb Broadway show.

|

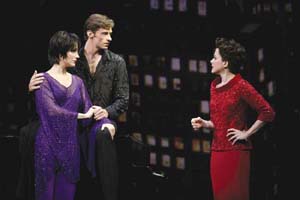

| Stephanie J. Block, Hugh Jackman, Isabel Keating, "The Boy From Oz," photo Joan Marcus |

"The

Boy From Oz"

Book by Martin Sherman. Music & Lyrics by Peter Allen.

Directed by Philip William McKinley. Choreographed by Joey McKneely.

Imperial Theatre, 249 W. 45 St.

212-239-6200

http://www.theboyfromoz.com/

Opened Oct. 16, 2003.

Reviewed by Lucy Komisar Oct. 23, 2003.

What can you say about the message of real life? This is a different kind of Oz - Australia. The story perhaps is how overriding ambition takes over the soul and can destroy all in its wake. Or, more generously, about the unyielding dedication of artists.

I never saw Peter Allen, about whom the play is made, but Hugh Jackman who portrays him is a consummate artist, a charmer, a showstopper, so here's where art seems to excuse the peccadillos of life.

The charming boy singer -- there's an engaging bit by the young Peter (Mitchel David Federan) at an Aussie saloon -- had a protective mother and an alcoholic father, and got out of the outback as soon as he could.

The problem with artists is that their egos demand audiences, not other artists. Liza had to deal with the added neurosis provoked by an overwhelming Judy Garland.

Allen (Jackman) fell into a family stalked by tragedy, so it's eerily unsurprising that this bisexual man saw his main chance in connecting with Garland (Isabel Keating) by marrying her daughter (Stephanie Block). They never really had a chance. Liza and Allen were both fixed on their own career successes, and then he turned out to be bisexual. Poor Liza: "If it wasn't for sex, we'd have been so happy." If only she had had the character and fortitude of the fictional Ruth, Eileen or Elphaba!

Though the story gets a bit melodramatic, well, hokey even, and it never makes me overcome my basic disinterest in the career paths of pop singers, Philip McKinley's staging is deft and entertaining. There's a witty satire of bandstand singers, smart sets by Robin Wagner, including tunnels that turn into a New York skyline, and all the voices are smashing. Jackman is sensual and riveting. Keating is stunning as Garland, and Block could be a double for Liza Minnelli.

|

| Alfred Molina, "Fiddler on the Roof," photo Joan Marcus |

"Fiddler

on the Roof"

Book by Joseph Stein. Music by Jerry Bock. Lyrics by Sheldon Harnick.

Directed by David Leveaux. Musical Staging by Jonathan Butterell. Choreographed

by Jerome Robbins.

Minskoff Theatre, 200 W. 45 St.

212-307-4100

Opened Feb. 26, 2004.

Reviewed by Lucy Komisar March 5, 2004.

There's no dearth of strong women in this fine revival of the 1964 play about Russian-Jewish peasants confronting modernity and pogroms. And they partnered by some very strong men.

Fiddler has always been anchored as an ethnic play, but this production makes it clear that the themes speak to all societies in social and political conflict. What rural society hasn't had a conflict over the role of women? What minority in an autocratic land hasn't suffered discrimination and reprisals? The value of "Fiddler" is that it speaks to this human condition, not to the experience of one group alone.

Demonstrating how it resonates, Angel Kreiman, former chief rabbi of Santiago, Chile, told me that some time after the 1973 coup, dictator General Augusto Pinochet called him to lunch. Pinochet, concerned about the influence of Jews around the world, wanted to explain why he had banned the 1971 film of "Fiddler on the Roof." Pinochet said, "You know, there are people running around with red flags against the Czar. I wouldn't like to show that to the Chilean people!"

This is why I was astonished by the hurt cries from some critics that this production isn't "Jewish" enough! "Fiddler" will live because it is universal; that makes it a classic.

The story of, of course, is both ordinary and exceptional. Tevye (Alfred Molina) and Golde (Randy Graff) worry about marrying off their daughters and get constant advice and suggestions from the Yente the Matchmaker (Nancy Opel) who proposes, for the eldest, a rich old man. The marriageable girls, alas, fall in love with youths who are inappropriately poor or of the wrong religion or have dangerously radical views.

Director David Leveaux seems to want to emphasize that their problems are part of a wider experience. The action takes place in an ethereal and glittery wood of birches often lit by glittering stars - evoking the familiar sets of plays by Chekhov. The men are boisterous in their drinking, not so different from the soldiers who first appear threatening, but then join them in dance.

Indeed, the book by Joseph Stein based on stories by Sholom Aleichem in turn-of-the-century Czarist Russia seems to be a tug between the humanity of everyone pulling together - of the radical Jewish scholar and one daughter going off to join the revolutionaries, of the Christian soldier tk going off to wed another daughter, and of the family finally setting off for America, where they'll still be a minority but one (relatively) at peace with Christian neighbors.

Alfred Molina is warm, vulnerable Tevye, who doesn't need much manipulating by his clever partner. Randy Graff leavens Golde's toughness with sensitivity. They do the famous musical numbers - "If I were a rich man," "To Life," "Do You Love Me?" - with charm and conviction, even if nobody brings down the house. Nancy Opel nearly does that with her "Topsy-Turvy" ditty with two busy-body compatriots. With his comic angular movements, John Cariani turns Motel the tailor into an unforgettable character.

The Jerome Robbins ballets are still dazzling. And Leveaux outdoes himself in the dream sequence when Tevye conjures up a ghostly vision that combines the woodland creatures of "A Midsummer Nights Dream" with a levitating apparition that rises heavenward in smoke. [Komisar]

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |