Dorothy Chansky

"My Children! My Africa!"

|

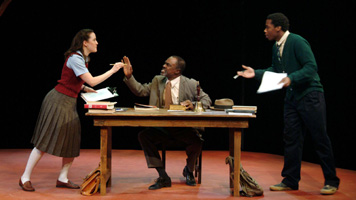

| Meghan Heimbecker, Glynn Turman, Yaegel Welch. Photo by Jim Roese |

Wilma Theater

265 Broad St.

Philadelphia, PA 19107

Box Office: 215.546-7824.

Closed January 7, 2007

Reviewed by Dorothy Chansky

Patriot, patriarch, patronym, patronize, patrol, patrician. What can you do with words starting with "patr"? Athol Fugard never phrases the question exactly that way in "My Children! My Africa!," but it's what he's after in this anti-apartheid howl that stages very real questions about the intersection of learning, legacies, love, and legality.

Fugard's 1989 play uses three characters to portray the tensions leading up to and during the 1984 "November Stayaway" in which South African students and workers boycotted school and work to protest grotesque laws devised to keep blacks down and out. Mr. M., a joyous, rigorous, and idealistic schoolmaster is grooming his favorite student, Thami, for a bright future on the Anglophone "best that's ever been thought" model. Thami is on the school's debate team, and when he's challenged (and beaten) by Isabel, a spunky girl from a British private school from across town, Mr. M. hatches a plan. The kids like and respect each other, so he pairs them up for a literature competition. The prize will enable Mr. M's impoverished school to acquire books and Thami to go to university.

The play is classically simple. Mr. M. calls hope a beast in his heart. He feeds it children. Act I shows his two favorite children learning about each other's worlds, boning up on Brit. Lit., and becoming pals. It also shows Thami chafing under Mr. M.'s cheery assumptions that words can conquer all and that teacher always has final say. ("Respect for authority is my only teaching aid," he confides to Isabel.) Thami's unrest is more than rebellion against a strict headmaster, though. The superficially oedipal is really the politically seething, and Mr. M. is merely the immediate representative of a whole system in which Thami will never be anything but a boy. So he vows to rise up. Act II shows his withdrawing from preparation for the literature competition as he starts attending political meetings. Their mixed result is a nation that speaks out coupled with danger and chaos. Mr. M. and his old-fashioned schooling are the obvious victims, but Thami pays a price, too, as he finally escapes with a rucksack and a vague destination, knowing that the police will likely find him anyway. Isabel will probably become the writer she always intended to be, but she is sadder, wiser, and less certain regarding the future for the country she both loves and despises.

|

| Meghan Heimbeckerl, Glynn Turman. Photo by Jim Roese |

Director Blanka Zizka chose to focus almost exclusively on her three superb actors, which was in some ways an obvious choice and in other ways risky. The play is long and talky, and Zizka's stage pictures were frequently static. (Think single long-shot in an age now accustomed to much action and frequent edits.) The actors were asked to stand and deliver and the audience to sit and listen with very little in the way of daring lighting, snazzy staging, or moving scenery as visual aids.

"Stand and deliver," though, was a challenge well met. Glynn Turman's Mr. M. was the teacher we all wish our kids had. Turman's superbly crafted dialect was by turns lilting and harsh, and it was impossible to miss his central conflict: Teaching and words are his entire life, yet seeing the colonial source of his power eludes him till the very end. Physically fluid, adept at being both debonair and defeated, Turman was in every way at the top of his game here. Yaegel Welch's Thami went from cowed kid to furious rebel with perhaps a bit too much bombast, but he maintained an intelligence and likeability that were hard to resist. Meghan Heimbecker's Isabel suffered initially from an almost too-textbook dialect, but her energy, precision, and emotional investment won out.

So, what about those "patr" words? Well, patriotism is tough when you have a love/hate relationship with your country, and in a country divided, both sides have reasons for both responses. Learning to pronounce "others'" patronyms can by the first step in claiming a shared stake and in overcoming learned patronizing behavior. Patriarchs with patrician aspirations for their children prove their mettle when those children are multi-racial. And if you're on playwright patrol, you know that Fugard's place in the twentieth-century pantheon is secure.

--Dorothy Chansky

| museums | NYTW mail | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |